Around 8pm every night I tell my wife, “I have a pit in my stomach.” “No you don’t,” she impatiently asserts. “You have a sinking feeling in the pit of your stomach.” Whatever I have, whether a void or pit, it aches. Being cooped up inside for who knows how much longer exacerbates a recurring feeling of anxiety. Of course, I am not alone, I presume you all feel something similar, and are coping as best you can employing the digital, analog, and pharmaceutical options available — and even trying to be creative as well.

But wait a minute, I’ve been here before and it was when my design career began, you might say. At seven years young in 1957 I spent a lot of time inside my bedroom making detailed drawings of customized fallout shelters. None were ever put into production, but this was the time when New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller encouraged building fallout shelters. In the suburbs they were carved out of basements or buried underground; in the city they were in all sorts of makeshift spaces where the yellow bold sans gothic World War II-era S-shelter signs were replaced with bright new orange Fallout Shelter ones with the black, triple-point triangle and the word “Fallout Shelter”. The ground level storage/bike room of the reinforced steel and brick Stuyvesant Town apartment building in which I lived, was designated as one such shelter.

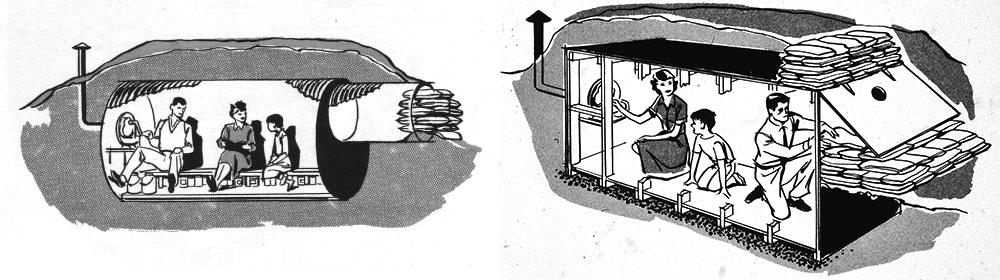

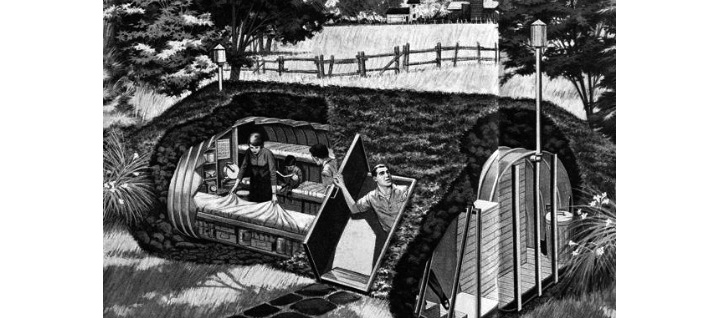

If I were to be cooped up in a shelter, however, this was not it. I wanted it to be filled with my middle-class creature comforts, not the rusty Army surplus cots that were stacked atop the large, sealed yet leaky drums of Saltines and other lifesaving supplies. That is why I drew and accumulated an extensive portfolio of underground habitudes that were pretty ingenious, if I do say so. They were based in part on Airstream campers and pre-fab efficiency bungalows, that were popular at the time, with all the basic necessities, including storage units, beds, tables, hotplates, etc. I hadn’t worked out how the power, HVAC or plumbing would work, but I was only seven, after all.

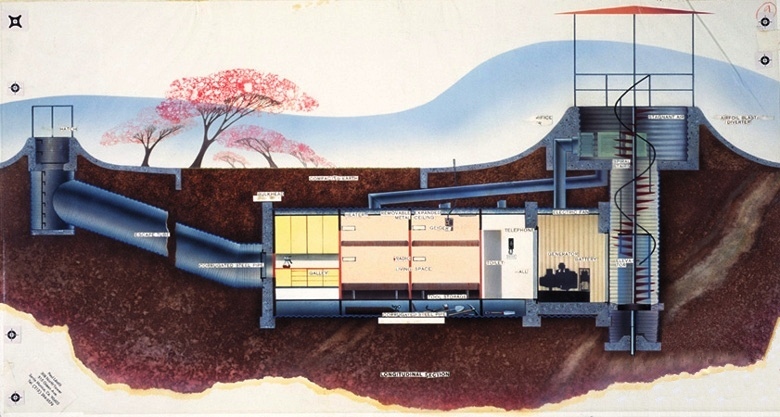

Part of my pre-teen years was filled with the anticipatory dread of living through a nuclear war. The government had promised in dozens of its free guide- and handbooks that if we followed duck and cover protocols in school and took part in air raid and confinement drills we would avoid succumbing to the radiation that would fall out of the sky after a thermonuclear blast. Although decidedly frightened by the recurring specter of a mushroom cloud outside my bedroom window, facing the East River across to Long Island City, I also anticipated its eventuality with a certain unhealthy excitement. The comfort of a shelter sort of lulled me into thinking things might not be so bad. In fact, my father, who worked for the U.S. Air Force brought home a very enticing booklet showing a range of Mid-century Modern looking luxury fallout shelters conceived by industrial designer Paul László for John D. Hertz in conjunction with the Air Force. It looked better than the blandly decorated apartment we already lived in.

Then one day, I don’t recall how old I was, my teacher told us there was a drill planned where, with the permission of our parents, a few of us would at intervals lasting one hour would be locked in a prefab shelter stored in the basement of the school. The experience was akin to placing us in a sensory deprivation box — or more like a residential iron-lung large enough to fit three people — with all the senses and none of the deprivations. The point, presumably, was to teach us useful survival lessons, the result, decidedly, was to mess with our heads, traumatize us and leave a lasting sense of PTSD (long before the diagnosis was ever listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders).

I lasted around fifteen minutes before the novelty became terror and I began pounding my fists and screaming. I was immediately released. Since then closed CAT-scans and MRIs have been impossible for me without a sedative. And although having been in social distancing-home confinement for now over six weeks (like so many others in the world) is not physically the same as being confined in the steel pod, the memory lingers. So, whether or not I actually have a pit in my stomach or a feeling in the pit of my stomach, its feels unhappily the same.