.png)

Zohar Studios

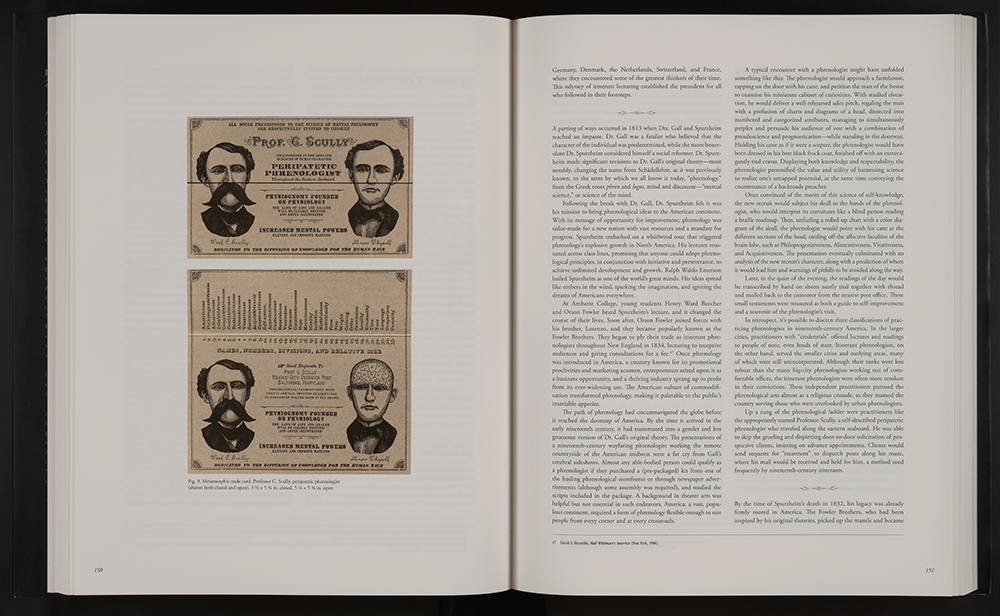

In the midst of this pandemic, I reluctantly had started divesting and pairing down my collection of over-sized artbooks, when I received a large, heavy box from Hat & Beard Press. Frankly, I did not need another volume that was too large for my bookshelves or heavy enough to strain my already aching back. Yet once opening the box and seeing the cover of Predicting The Past — Zohar Studios: The Lost Years by Stephen Berkman, I was seduced by the sepia photograph of a Victorian era woman wearing a period dress festooned with dozens of framed tintypes and holding an elaborate velvet banner with the words Zohar Studios embroidered in script (did I mention she was on roller skates?). Too heavy to hold on my lap, I lugged the tome to the dining table and began paging through what I believed to be a very tasteful, handsomely designed collection of vintage yet somewhat curiously odd nineteenth century studio photographs – commonly sold in flea markets – by an unknown commercial photographer from the days when our ancestors stood or sat perfectly still in front of elaborate painted backdrops and dioramas for long exposure times.

.png)

Conjoined Twins

I enjoy perusing these kinds of artifacts, often imagining the subjects’ lives before and after they are captured on film – who they were, where they were from, what was their status and why, for instance, did they choose one background over another. Yet these Zohar Studio photographs were decidedly different than the typically common antiquities. I felt a hypnotic force was coming over me. Turning the pages I was transported into a surreal sphere that was created, as I read in the text on the exquisitely typeset pages, by Shimmel Zohar, a Jewish immigrant from Eastern Europe “who came to America in the 1850s. Already an accomplished silhouette artist,” the proprietor of eponymous Zohar Studios, a storied photographic establishment located on Pearl Street in the predominately Jewish Lower East Side of New York, replete with “a Balzacian cavalcade of characters, both winsome and whimsical.”

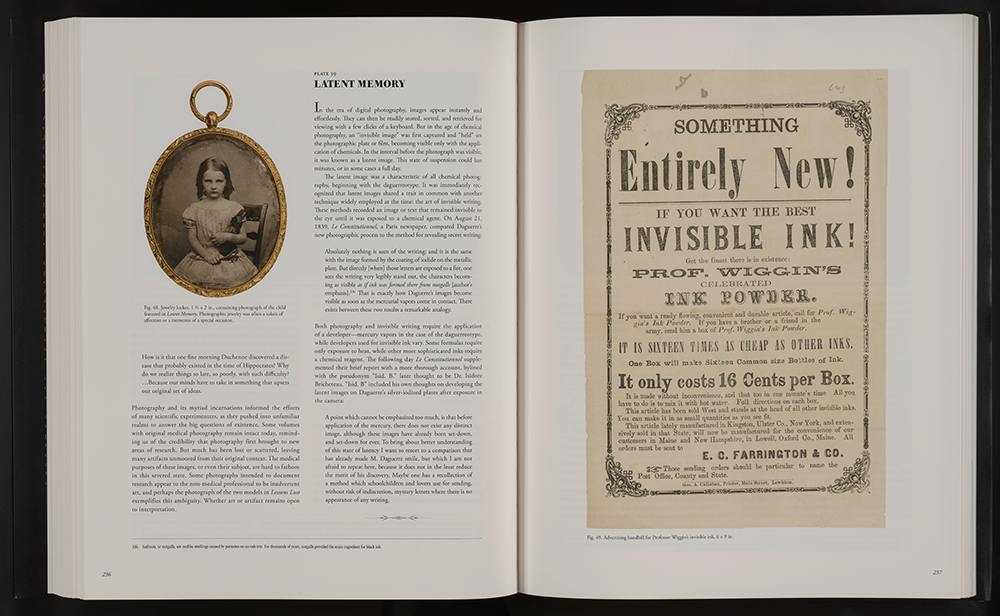

.png)

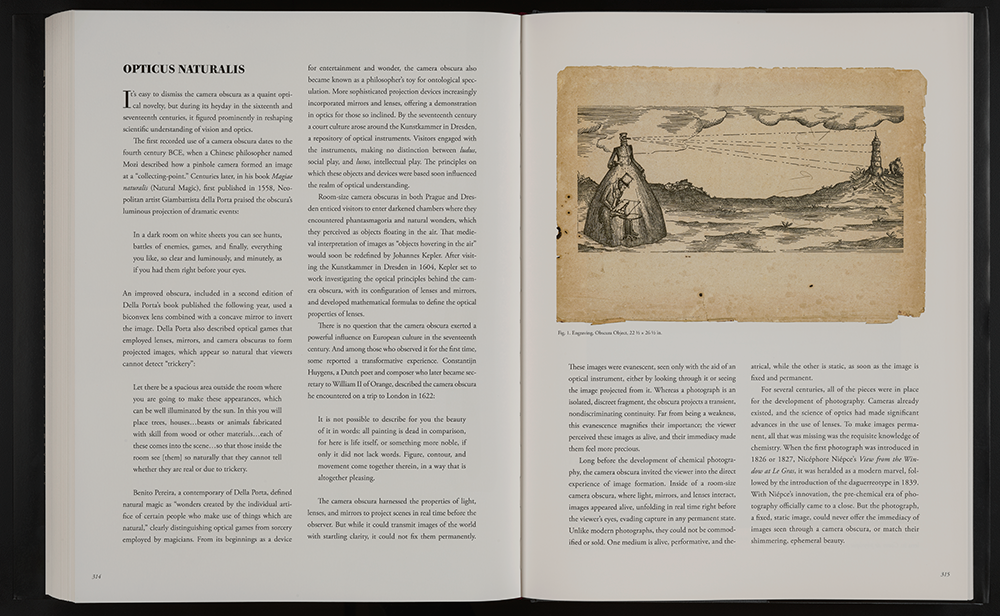

Obscura Object

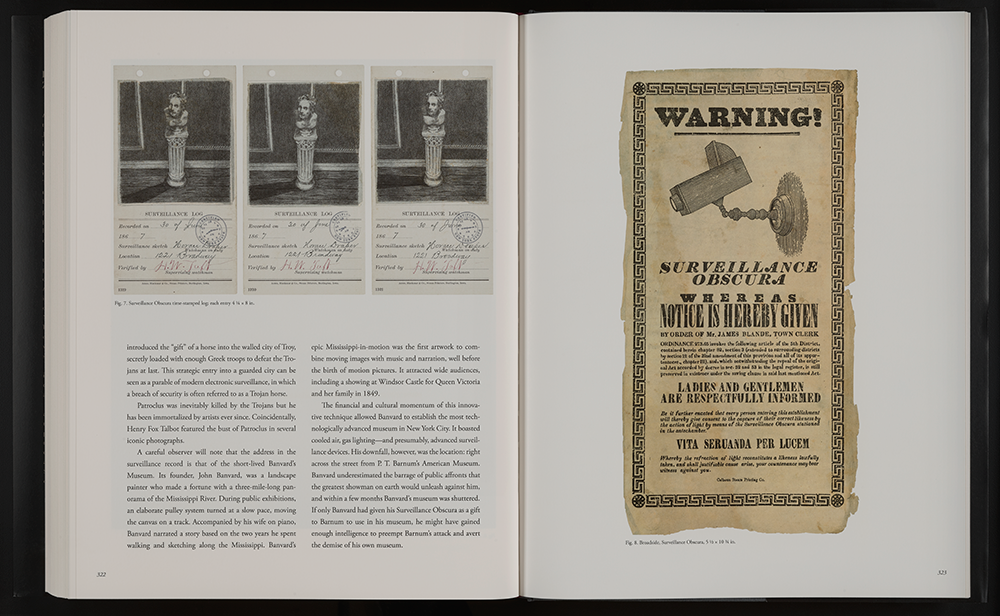

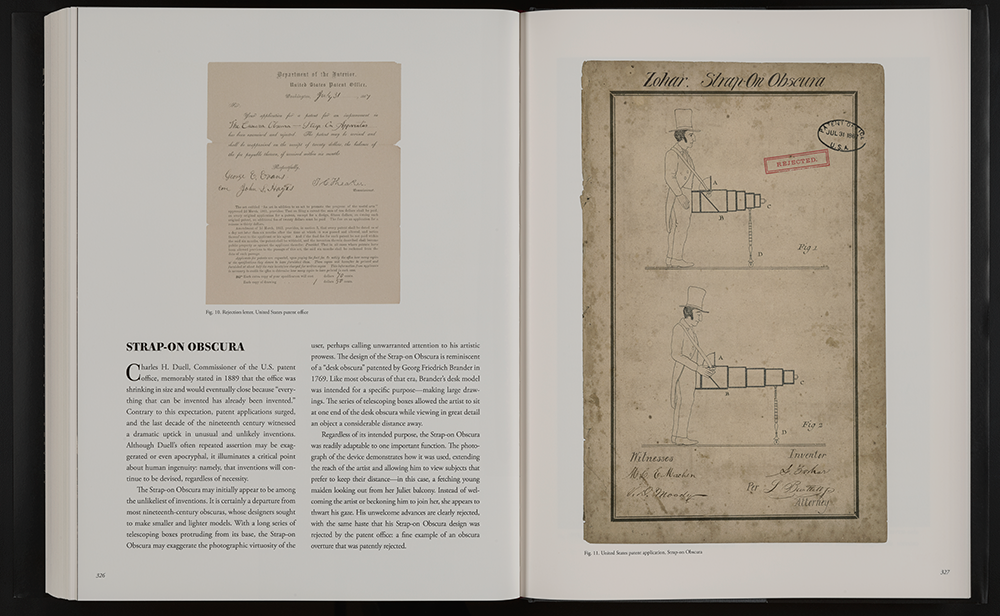

Assuming this was one of those enviable, extraordinary discoveries found in some long abandoned warehouse or attic, I allowed that this book was a deserved presentation of the work of a forgotten, if eccentric, genius. I wondered how the photographic material and studio ephemera (advertisements, billheads, etc.) were so well preserved and respectfully conserved with such careful archival care. Rather than a burden (i.e. so now what will I do with this over-weight book), I considered the deaccession of more of my books to make room, or constructing a book pedestal, for this hefty volume. Not until reading more of the text and finding a few anomalies amongst the photos did I realize that Stephen Berkman did not simply stumble upon Zohar’s lost cache but his involvement is more proactive – indeed creative – in terms of the wit and talent that pervades this entire (images, text and design) remarkable work. After scrutinizing his slightly enigmatic biography on the jacket flap, I wanted to learn more about Zohar and Berkman’s particular role in documenting and bringing Zohar Studios’ treasures to our attention. Last week we engaged in the conversation below and I learned there’s more to Zohar’s photography than meets the eye.

.png)

A Wandering Jewess

_.png)

Shtetl Shtick

Steven Heller: When did you begin your interest in and work on this elaborate, dramatic, mysterious 19th century aesthetic? And why were you so inspired to create such an elaborate production?

Stephen Berkman: This preoccupation dates back to a young age when I found myself slipping into reveries that had the semblance of nineteenth century illustrated engravings. These trance like states can only be described as nineteenth century fever dreams where everything appeared phantasmagorical, like a kind of second hand surrealism that subverted Victorian formalities. Later when I discovered Max Ernst’s surrealistic visual collage novel Une Semaine de Bonté, and Harry Smith’s animated film Heaven and Earth Magic, I recognized them as kindred spirits, and creators of a new visual lexicon.

Innovation was at the heart of the nineteenth century, which represented an era of exploration, discovery and invention, and most importantly it was the century that gave birth to photography. The world was receptive to new scientific revelations and there was a sense of accelerating headlong into the future. But the framework was still incomplete, and blanks in the collective knowledge were often filled in with fanciful explanations. Photography was developed out of this critical mass of science and magic, and hopefully this book embodies that spirit.

SH: Zohar created a movie stage set for each photograph. Can you say why?

SB: There’s a theatricality to photography that is unavoidable. From one perspective, the photographs in my book can each be seen as a single frame film, and the book as a whole as a cinematic experience. The performative aspect of photography can be traced back to its beginning with photographers such as Hippolyte Bayard who created the first narrative photograph. The nineteenth century portrait studio is the perfect proscenium, an elaborate stage set complete with backdrops, furnishings, props and sometimes wardrobe where an ordinary person could appear more resplendent, stately or prosperous than in real life. Painted backdrops were instrumental in facilitating theatrical illusions and they provided an early transition point between photography and film. An example of this convergence can be found in the work of photographer Paul Nadar, the son of seminal French photographer Felix Nadar. Paul photographed opera stars and ballet dancers in elaborate costumes against painted backdrops in the studio. The performative nature of his subjects inspired him to study movement in film. He pioneered early film techniques, designing and patenting his own film camera in 1896, which he employed to document moving subjects, including dance performances and theatrical scenes.

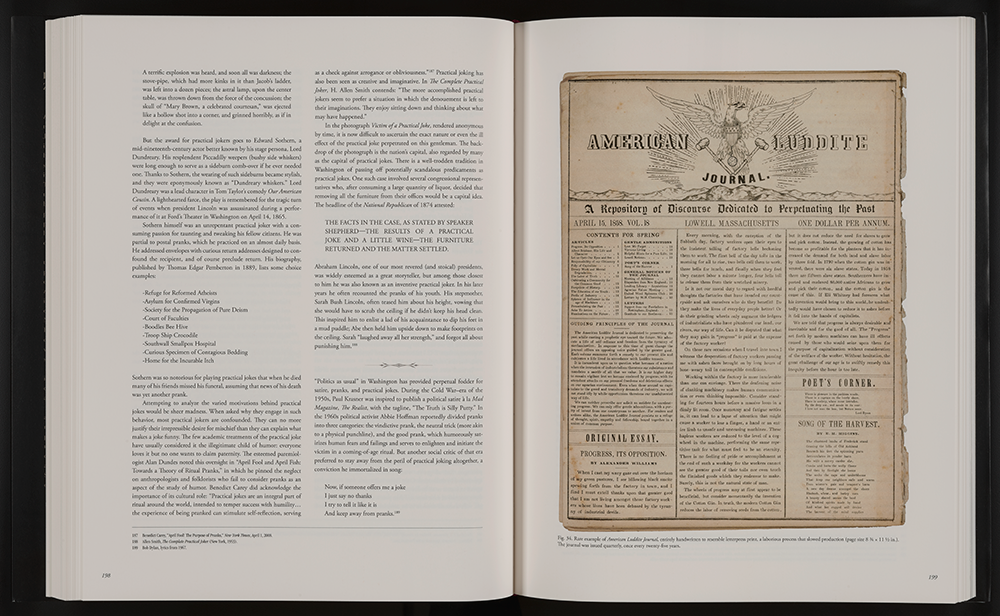

.png)

The Vicitim of a Practical Joke

.png)

Remedy for Reverie

SH: They are amazing in so many ways, not the least is that the theatrical style and cinematic language is spot-on.

SB: I’m drawn to this intersection between photography and film during this nascent era. Almost immediately film diverged into opposing genres, each with their own visual vocabulary. The Lumière Brothers’ early actuality films documented quotidian scenes from life that established a basis in reality, such as Workers leaving the Lumiere Factory. Conversely, the mis-en-scene films pioneered by George Méliès departed from reality into a world of cinematic illusion concocted entirely in his studio, relying on elaborate sets and experimenting with camera techniques to devise the first special effects. One could view the photographs in my book as a blending of these two genres. It’s difficult to say where one ends and the other begins.

SH: Your jacket flap author’s photo answers a lot of questions for me as to where Zohar derives from. You seem to be your work and your work is you. How much of this, shall we say, faux persona is your real persona?

SB: My countenance on the flap jacket is actually from an oil painting but it has a photo realistic quality. Perhaps it can be taken as incontrovertible proof that I’m not just another nineteenth century interloper.

.png)

.png)

SH: Your live models are pitch perfect. What betrays the mystery of who is the real Zohar is a scene in the book with late actor and magician Ricky Jay. Yet even he looks like he was alive during the time period. Where and how do you cast your actors?

SB: Throughout this process I was guided by moments of serendipity. In many cases I encountered potential subjects by chance. My experience has led me to see the universe as predictably random. There’s a Hebrew word bashert that describes this phenomenon of destiny in daily life. There’s a sense of being in the right place at the right time for providence to intervene. Any time I go out into public I’m scrutinizing people to find an anachronistic face that could have inhabited the nineteenth century—people of that time had a different physicality and physiognomy. Sometimes it took years to find the right person for a photograph. For one particular image, I drove across the continental United States with my portable darkroom, collodion, and studio camera in tow to capture the likeness of an individual who personified an ideal nineteenth century archetype.

I encountered Ricky Jay in much the same way. I met him at random and introduced myself and discreetly disclosed that if he was ever in need of an ambrotypist* to please get in touch with me. Ricky is the only person in the book who is well known and recognizable. He was a good friend and a far reaching influence. He was more versed in esoterica than anyone I’ve even known.

* The ambrotype, introduced in the 1850s, is a photograph on thin black-lacquered iron, which evolved into the tintype.

SH: Do you use and collect period equipment?

SB: If a photographer from the nineteenth century awoke from a coma, they would feel at home in my studio and would be able to get right back to work without a hitch. There’s still a continuity between now and the nineteenth century—in reality not much time has elapsed. If you look around you’ll find many overlapping features still in existence today, buildings, art, objects, literature and ideas. When I began this book there were literally thousands of people from the nineteenth century still alive. As it was nearing completion, the last person from the nineteenth century died in Italy, and with that, there is a feeling that the century finally came to an official close. Time has elapsed, but it’s like a blink of the eye when you consider the scale of eons. The art of photography takes into account the nature of time. Capturing images in a sticky photo emulsion, photographs that remain from that century are moments frozen in time. Like dinosaurs trapped in tar pits or inhabitants from the ancient city of Pompeii who were frozen in a lava flow, life is reduced to a single moment encased in time. In photography it’s not the actual person who is captured in the film emulsion, but a facsimile of them, a simulacrum. Still, it represents a true moment in history. This is why Balzac detested photographic portraits, because he felt they had the reductive impact of compressing a full and rich life into a flat and narrow glimpse. His writing process had the opposite effect. He could expound upon a single moment and transform a simple observation it into a vivid cacophony of interpretation.

SH: I'm trying to imagine what your studio is like and what must your neighbors think?

SB: I’m pretty certain I’m the only person in my neighborhood with a nineteenth century photography studio. It’s a skylight studio completely hidden from street view. You would never expect to find it here—for me it’s an oasis in an urban desert. Likewise, George Méliès had a studio behind his house and he recreated scenes of wonder in that humble building. The walls of the studio are not the studio itself they only provide a space for the imagination to roam and ramble.

SH: In addition to the images being pitch perfect, the wit is beyond the kitsch of steampunk and as deadpan as Edward Gorey. Yet your subjects are so dark. How do you maintain that balance of nightmare and sunlight?

SB: There’s a certain Jewish perspective of the world that comes through in the work. Jewish humor, born of pain and angst and the recognition of the absurd, takes into account the paradoxical state of our existence. It’s so engrained in who I am that I can’t separate myself from the aesthetic. Humor is a large part of how I see the world and I hardly question it. It’s just second nature to me. It’s my hope that this book comes across as a curious blend of vaudevillian performance imbued with a dollop of comic poetry.

SH: This is such a mammoth project. What is next for you?

SB: The Zohar saga continues. I’m currently working on a fourteen-foot tall version of the camera obscura woman that was featured in the photograph Obscura Object. The larger scale model with its more spacious interior will foster a more interactive exhibit, allowing people to enter the tent obscura concealed under the skirt, and witness the enlarged images projected from the prism lens inside the darkened chamber to facilitate a direct experience with photography. My plan is to take this oversized obscura to Niagara Falls, which was a popular nineteenth century tourist destination. It was once a traditional location for daguerreotype photographers such as Platt Babbitt and the brothers William and Frederick Langenheim who used the magisterial falls as a scenic backdrop for their portraits of visitors.

I’m also working on an audio version of my book in order to encourage reader involvement with the text. Photography books are so rarely read, although one could argue that some “read” the photographs, so to speak. My book contains about 130,000 words of text, including Lawrence Weschler’s extensive afterword essay The Road to Zohar, (for comparison, Melville’s Moby Dick contained around 206,000 words). To my knowledge, this may be one of the first audio photo books. It’s narrated by Nick Landrum, whose melodic baritone voice brings the words to life in a compelling chronicle. In the end, I see it as an homage to talking pictures—the next logical step.