I felt queasy entering my office last Friday for the first time in almost nine months, since the Covid-19 lockdown in mid-March. It was akin to visiting a museum diorama — a recreation frozen in time like W.A. Dwiggins’ studio at the Boston Public Library, or Theodore Roosevelt’s bedroom in his historic birthplace on 20th street, or actor Edwin Booth’s (brother of John Wilkes Booth) bedroom preserved at the Player’s Club on Gramercy Park. My stuff was there but I was not. Eerie!

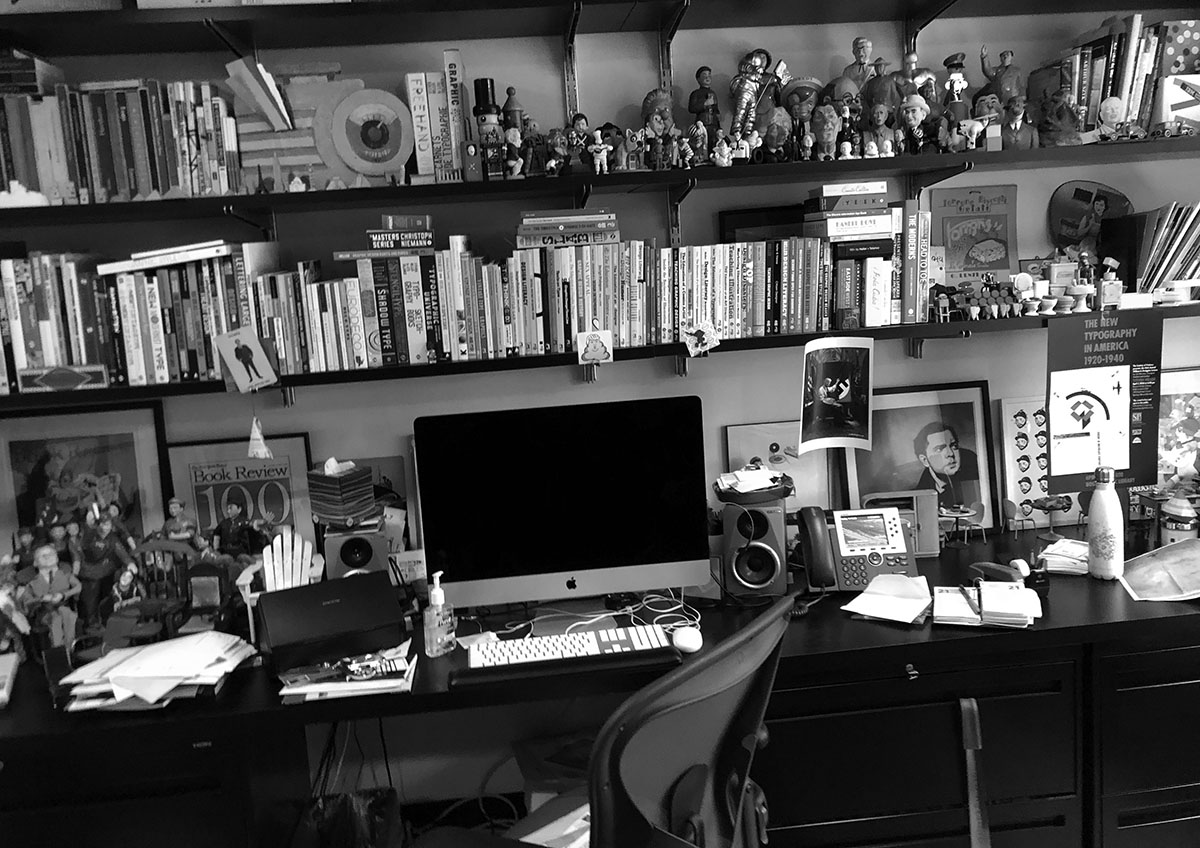

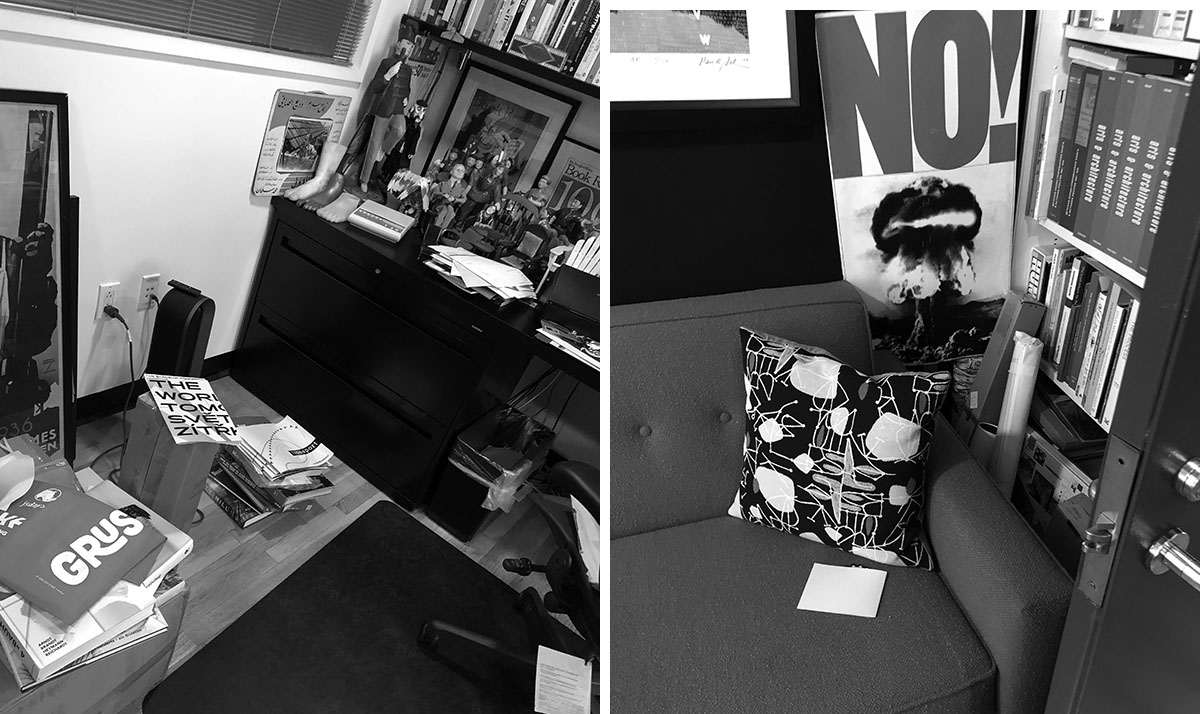

It made me feel sorry for people who do not have personal offices. Those who have them are no smarter or better than those who do not. I am privileged to have a private room to work in that is an extension of my personality. My office is definitely a reflection of who I am. Amid the extreme clutter, my office is a portrait, filled with art and artefacts that defines who I am and what I do. For the course of this lockdown doctors have forbidden me from using my office. Now, there are moments I don’t know who I am.

I have become a displaced person.

The other day, after hearing the news from Mayor DiBasio that a second lockdown was imminent, I walked the 1.5 miles from West to East sides of New York City to my office building and stood outside in the warm drizzle for about fifteen minutes, looking up to the fifth floor, carefully assessing the risks of entering. I knew that only one other colleague would be in the studio and I could probably keep a protected social distance. My intent was to sign in, enter an empty elevator (although it had been occupied immediately before I entered), follow the stringent safety protocols, and sit at my desk just long enough to gather a few necessary belongings. I determined the odds were favorable for a very brief visit before the virus knew I was there.

So, after considering the options (and ultimate logic), I couldn’t abide being so close yet so far. I took the plunge and what a host of uneasy, uncertain, uncomfortably displaced feelings it evoked.

It did not help that I had just finished reading Earth Abides by Geroge R. Stewart, a 1949 novel in which the world’s human population is decimated in a matter of weeks by an incurable virus. Yes, it was a bad idea to read it in the first place (thanks Amazon!) but I thought I could handle it.

The novel is set very near Los Angeles in a small community of survivors that gradually grows from two to 200 over a period of fifty years since “The Great Disaster.” The mysterious disease, which apparently disappeared after the masacre is followed over time by alternate infestations of ants, rats, locust, rattle snakes, wild fires, and the uncontrollable decay of infrastructure, including loss of electricity, water supply, and a batch of surprise epidemics. The plot traces the life of protagonist, “Ish,” (short for Isherwood), who, at first alone, finds a stray beagle he names Princess, then eventually meets other nomadic survivors, notably Em (Emma), an older woman who embraces his company. They mate, spawn children and form The Tribe in order to start anew. Watching the new Borat movie was less depressing in one sense though more wince-inducing and worrisome in others. However, Earth Abides was so craftily constructed in terms plot, characters and setting, it was painful. Although I considered stopping at various times, I stuck with it to learn the fates of all concerned. (Sorry, no spoilers from me.)

Entering my office for the first time since March, I felt a bit like Isherwood upon returning to his native California birthplace a few months after surviving The Great Disaster and finding it was just as his missing and presumed deceased parents had left it. Everything was the same but nonetheless different. My office was the same, though messier than I remembered, filled with unopened piles of mail — letters, zines, and book boxes. It was sanitarily clean, because the cleaning staff was given access on a regular basis. The windows were even washed for the first time in years. Still it was hauntingly disconcerting.

To be certain I am making no false equivalency: I was not displaced by the same devastation that refugees from war or natural calamity lost their all property, homes, countries, and families. I still have a home, family, friends, and possessions. If I choose to break my doctors’ dictates, I can risk returning. But the sensation of being displaced (or rather detatched) from who I am and what I do was profound. I took a few seconds to reminisce and retrieve two random items before, in my mind, I imagined those microscopic covid-19 plush viruses massed for an attack. So I left quickly without taking what I originally came to repossess, I guess now on I’ll wait until the war is finally won before I return.