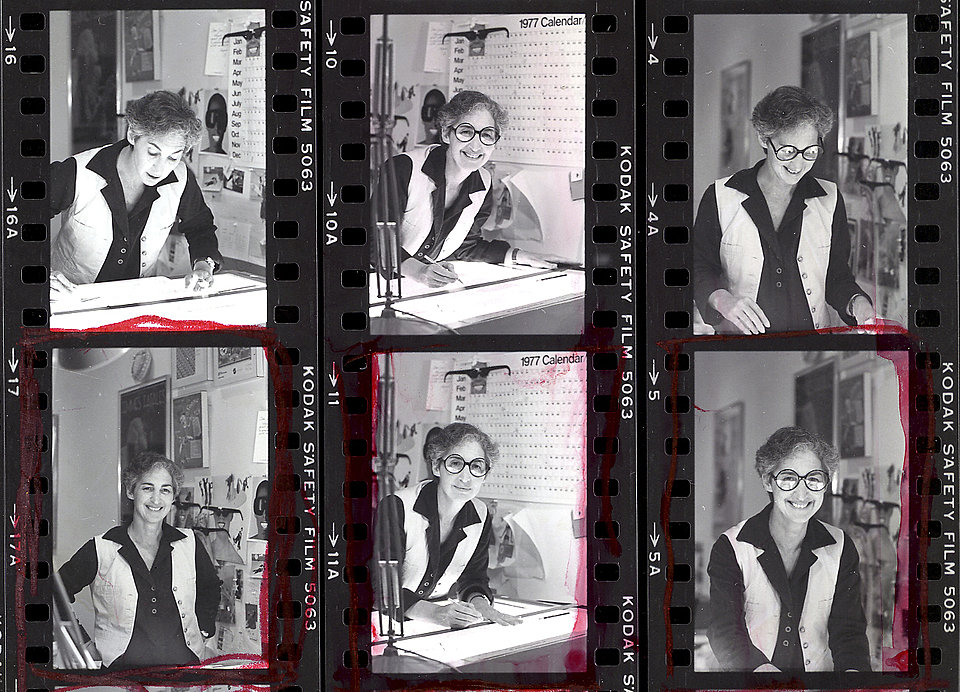

Mickey Friedman in the Walker design studio, photo contact sheet, 1979 (Photo: ©Walker Art Center)

Thursday morning I awoke to news of the passing of an important design thinker and advocate. Mildred Friedman, known as “Mickey,” was the editor of Design Quarterly and the Walker Art Center design curator for much of the ’70s and ’80s. In collaboration with husband Martin Friedman, she organized major design exhibitions including Sottsass/Superstudio: Mindscapes (1973); New Learning Spaces and Places (1974); Nelson/Eames/Girard/Propst: The Design Process at Herman Miller (1975); De Stijl, 1917–1931: Visions of Utopia (1982); The Architecture of Frank Gehry (1986), the architect’s first major museum exhibition. I remember her most for the controversial yet ground-breaking Graphic Design in America: A Visual Language History (1989), the first major museum survey of the field in the United States.

It was my involvement with A Visual Language History (such a great title) that introduced Mickey to me. She had invited me to Minneapolis to discuss the prospect of building an exhibition on the foundation of Philip B. Meggs’s pioneering A History of Graphic Design in association with AIGA. It would indeed be the first serious American museum survey on the history and contemporary practice viewed through the lens of graphic design as lingua franca. Mickey had no doubts it would cause a stir in the museum world.

She was a formidable presence, dominating a room with her knowledge and confidence. And it soon became clear that she did not want to follow Meggs’s narrative, which was arguably based on a cannon that emerged from New York with its great master legacy. Mickey’s goal was to include newer experimental and theoretical approaches while respecting the mid-century Moderns who defined the 20th Century design ethos.

Mickey was deservedly admired, but her primary expertise was with architecture and industrial design. Graphic design history was somewhat new territory. At first, I was concerned that she was treading on and, therefore, disrupting established legacies but realized quickly that her fresh perspective was valuable, if only to stimulate debate on issues like theory and practice, style and content, decoration and function and gender. I signed on to do a series of interviews for the catalog with significant players in the design world, Saul Bass, Milton Glaser, Ivan Chermayeff, April Greiman, Muriel Cooper, Leo Lionni, Bradbury Thompson and Paul Rand. Nonetheless, when the exhibition opened, initially at the Walker and year later in New York at the IBM gallery on Madison Avenue, there were some missing players (including Milton Glaser) and genres (including illustration). Years later Ralph Caplan wrote:

“The show disappointed many designers who felt that the selections were arbitrary and not accurately representative of the field. Friedman countered that professional designers, accustomed to submitting their work to be judged by committees of their peers, were — unlike, say, painters and sculptors — simply unaccustomed to curated shows. Heller organized and moderated a public panel discussion of the issue, which was held at The Cooper Union. Like most panels, this one settled nothing; but it did clear the air enough to allow for general agreement that a much less grandly promissory title would have been more accurate.”

Mickey was adamant about the rightness of her selection, but open to the criticism. Her participation in the panel proved she was able and willing to both defend the show against some strong attacks, but also entertain other points of view that were expressed in the design press.

In hindsight, she was right, of course. This was a curated exhibition. That it was the first (and some believed possibly the last) to so signifcantly showcase design history, made the rewrite of Meggs’s cannon somewhat threatening. But Mickey showed us all that an educated critical point of view was not only possible but necessary if the field was to be more than a craft. For this I have great respect and admiration for Mickey Friedman. It is sad to see her go.