Night sky over Puget Sound, 2009. Photo: Dan Mauch

At the same moment that we are increasingly conscious of the dangers that man-made lighting poses to birds, plants, wildlife and our own biological rhythms, we’ve become ever more enthralled with the artistic and architectural power of radiance. Whether we’re talking Las Vegas, Shanghai or New York, the seductive draw of urban glow has never been greater. Below, Susan Harder, a leader of the Dark-Sky movement, and Leni Schwendinger, a crusading lighting designer, attempt to tackle the issues of light pollution in urban, suburban and rural settings. Susan, whose organization advocates for greater regulation of lighting practices and Leni, known for creatively illuminating landmarks such as the Coney Island Parachute Jump, would seem to sit on opposite sides of the fence. But as this discussion reveals, they both agree that a more thoughtful approach to lighting, rather than an across-the-board reduction, is the best way to tackle the problem.

Coney Island Parachute Jump illuminated by Leni Schwendinger Light Projects. Photo: Archphoto

Karrie Jacobs

I’d like to begin with a quote from “Our Vanishing Night,” an article by Verlyn Klinkenborg that appeared in National Geographic last year:

Of all the pollutions we face, light pollution is perhaps the most easily remedied. Simple changes in lighting design and installation yield immediate changes in the amount of light spilled into the atmosphere and, often, immediate energy savings.

The quote suggests two questions that I thought would get the ball rolling:

1. Are the changes that need to be made to lighting design and equipment indeed simple?

2. Is there any kind of consensus as to which lighting practices constitute pollution and which are essential?

Susan Harder

I agree with Mr. Klinkenborg. I’ve changed a great many outdoor lighting fixtures and have been able to provide a return on investment within five years. In one case of a post-top streetlight on Main Street in East Hampton, New York, we halved the wattage and provided better-quality light on the ground. As a benefit, the residents felt that the new fixture reduced glare and was more attractive. It also reduced the light hitting treetops and entering peoples’ bedrooms. In such cases, not only is money saved through energy conservation, but “light pollution” (misdirected, excessive, unshielded or unnecessary night lighting that produces glare, light trespass and sky-glow) is greatly reduced. We are lucky that correcting light pollution is so cost-effective.

So in answer to your first question, yes, changes that need to be made in lighting design and equipment are simple, if they are followed. Good equipment exists (and more is being developed), as does good design criteria. Without regulations and municipal policies to mandate better lighting practices, however, better lighting will not result. While you can see many good lighting-design installations in New York City, for example, they are usually the work of an “enlightened” lighting designer who has been hired for the project. New York, like many major cities, has few to no regulations for outdoor lighting. Regulations will allow a review process prior to construction to assure a better type of light fixture, the correct amount of light to see well and automated shutoffs to extinguish the light when it is not needed. The type of light bulb should be energy-efficient while not adding unnecessarily to sky-glow and maintenance costs.

As to your second question, essential lighting need not result in light pollution. Light pollution is the result of no criteria, poor design, no lighting plan review and incorrect installation. Unfortunately, most of our installed outdoor lighting produces light pollution in all its forms.

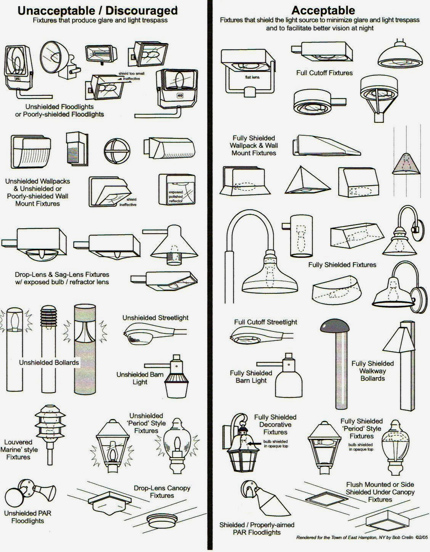

Acceptable and Unacceptable Lighting Fixtures for East Hampton, NY. Courtesy Susan Harder

Leni Schwendinger

Mr. Klinkenborg presents a dire vision of “light spilling into the atmosphere” — purportedly analogous to dumping industrial waste or raw sewage into a river. Thus pollution frames the discussion in misleading terms. In his article, he evokes early-19th-century London, where people made do, he says, “as they always had, with candles and rushlights and torches and lanterns” (with no mention of Jack the Ripper — 1888). But refer to Wolfgang Schivelbusch’s book Disenchanted Night: The Industrialization of Light in the 19th Century to discern the original motives for public lighting — ease of nighttime travel for those without a carriage and horses, reduction of crime and even more subversively, the start of social control in the public realm. These are the complexity of issues at hand when we discuss urban lighting.

I am not “for” light pollution — nobody is. I am for good lighting: illumination that serves a purpose, in the sense of safety (I can identify the mugger or rapist walking toward me), tasks (reading maps on a city street), identification (am I in Times Square?), and illumination that enhances our city nightlife for the greater good. In this case, it means helping small businesses attract foot traffic, cheering up long stretches of badly designed or neglected streetscapes for nighttime strolling, creating enclaves for social space at night — plazas, pocket parks — and ameliorating the visual environment where infrastructural forms like ramps, highways and vacant spaces cut across our cities.

I am against glare, pointless commercial lighting, badly conceptualized lighting and needless light trespass. If sky-glow is reduced, lighting designers will have all the more incentive to create beautiful light environments in cities with an ideal, darker backdrop of the night. For example, our lighting design for a large park on the outskirts of Shanghai designates swathes of darkness for nocturnal wildlife purposes.

1. Are the changes that need to be made to lighting design and equipment indeed simple?

Let us set the stage for this question, which is situational. The exurban and suburban contexts must be distinguished from the urban and roadway environment.

Exurban/suburban problem: My neighbor’s floodlight is aimed across my property line, or their ornamental maple is up-lit. Solution: Focus the light onto the driveway; turn off the up-light two to three hours after sunset and voilà — light pollution on a small scale is averted!

Does a stretch of street lined with lantern post-tops really cause light pollution? How do we reconcile our love of the gas lantern with our desire to reduce sky-glow? The charm of the authentic lantern form, depending on its design, resides in the visible light element (mantle or flame) or the glow of the translucent glass. What to do about the instinctual joyful human response to sparkle — generally caused by decorative post-tops, string lights and other unshielded fixture tops? Should there be a blanket ban on all up-lighting, even though illuminated large-canopy trees, with their branches and colorful leaves, create a romantic landscape loved by many? And what of innovative applications of light, such as the 9/11 Tribute in Light memorial — up-lighting at its most extreme, which in principle could be disallowed by light-pollution ordinances?

Harder

I know of no lighting codes that would ever restrict “public monument” lighting. In fact, the 9/11 memorial light piers are voluntarily restricted to a specific time frame due to the problems associated with “up” lighting of that magnitude. Lighting codes will require commercial searchlights to receive a permit from a governing board.

Schwendinger

In the case of urban lighting, I believe that a consensus is not yet achieved, although the yearning for energy savings — and to help to save the planet — is. There are very exciting developments in the arena of electronic control for city lighting. These technologies will allow us to dim and turn off the essential publicly provided lighting in the future on a district-by-district basis. I believe that satisfactory solutions will be created with the involvement of local communities and designers. However, there are obstacles: For cities that rely upon existing locations for streetlights (for economic reasons) full cut-off optics are not always a valid solution. Physical, political and economic constraints make change difficult. And, questions of light pollution aside, the differing subjective values of a large metropolitan city with regard to its visual appearance is also a factor.

Easy prescriptions are not always correct, and comprehensive solutions are never simple. Ultimately, there is more to light pollution than light… a complex of social and economic factors as well as those of the built environment (design and architecture) also define the solution.

2. Is there any kind of consensus as to which lighting practices constitute pollution and which are essential?

There is no consensus. I have not yet seen the scientific response to, let’s say, the measure of pollution from up-lights versus bright surface lighting (roadways), facade lighting or high-masts — these are the current culprits we focus on.

Visit a city such as Las Vegas, New York’s Times Square…or Shanghai. In these places, spectacle is the norm for local character and identity, and although Las Vegas is located in a beautiful desert with an awesome view of the dark and starlit sky, the value of the commercial beacon has trumped the value of stargazing. Rural populations tend to agree on the privacy of property lines. Metropolitan populations range from “24/7” lifestyles where “the city never sleeps” to those living a balanced life, respecting circadian rhythms, in a city environment. Additionally, the “third shift” workers in large cities (transit, shipping, cleaners) have particular nighttime needs. And speaking of class, is there a single citizen living in a blighted neighborhood who would prefer less light? Is there a cop or first responder in a densely packed modern city who would call for reduced light levels in deference to the darkened night sky?

Jacobs

A number of thoughts and questions came up while reading your responses.

Both of you seem to agree that there is a difference between urban lighting practices and suburban/rural practices. Susan, I thought it was interesting that you believe lighting design in New York City is often more enlightened (so to speak) than lighting design in outlying areas. Does that mean there is less need for regulation in New York and other urban areas?

Harder

Quite the contrary: New York needs regulations to assure quality lighting. I was only saying that there are “good” lighting designs in the city because of access to expert lighting designers. Most communities do not have this resource, and the local architects and electricians are not trained in outdoor lighting. Regulations in those towns will outline criteria so that good lighting can be achieved for most utilitarian projects (e.g., parking lots and doorways) without a design expert. We have been using “Guidelines for Good Exterior Lighting Plans” here in East Hampton for years, and the results are terrific. The architects work with lighting manufacturers, giving them the criteria, and good plans can be achieved. Manufacturers will provide free lighting plans.

Schwendinger

Please note here, the important international lighting designer associations IALD and PLDA specifically cite the practice of manufacturers’ providing free lighting plans as detrimental to the profession — in fact lighting designers employed by manufacturers may not join these organizations (they can, however, join IES [Illuminating Engineering Society]).

The practice of manufacturers supplying free design services is quite controversial. The plan may be free, but the fixtures are from a single source — that manufacturer’s. In essence, the lighting plan is a potent sales tool and at the same time undercuts the professional lighting designer.

Harder

While there are great differences between “urban” and “rural” environments, a person still needs the same amount of light to see objects/walkways, etc. And our cities are full of trees (negatively affected by all night lighting) and birds (traveling through on migration routes) that can benefit by better lighting practices.

Cities may choose to light more elements of architecture than rural areas, and to leave more lights “on” in cities that are active 24 hours. But “the city that never sleeps” actually is a city full of people who do want to sleep at night, and in their apartments without light intrusion, if possible. Even our bridge lights (decorative “necklace” lights) are shut off in the middle of the night. I can see the full spans of the Verrazano, Williamsburg, Manhattan and Brooklyn bridges from my apartment on the East River in Brooklyn, as well as the tops of most of the architecturally significant skyscrapers. I appreciate seeing the bridges and buildings lit, but I understand that it’s important to seek balance. They should also be lit properly.

Jacobs

Leni, highway and main-street lighting may be essential for reasons of safety and pure functionality. But you suggest that much urban lighting is essential in a different way: light becomes an architectural element, a landmark and a component of a city's commercial well being. Do proposed regulatory mechanisms take urban lighting needs into account? Should cities be regulated differently?

Schwendinger

Interestingly, roadway (read “highway”) lighting is the generator of street lighting (as in city and “streetscape”) standards. There is a spirited discussion going on about whether the IES should have a separate committee for urban lighting; it does not presently. I am skirting the issue of regulation somewhat — standards are different from regulations — because I really do not believe there should be regulations, but a high level of motivation for implementing standards. Standards can change more easily than regulations, and it seems that standards may be more research-based than regulations, which I think (really, I am going out on a limb here) are more politically based and possibly influenced by the market. Certainly, if we have to have regulations, they should be very locally based and have change options built in.

Harder

I have found that municipalities generally adopt “standards” or “policies” with regard to their own practices. Laws are enacted to regulate private development so that building departments can require certain community standards prior to construction, and so that the municipality would have legal recourse to enforce the regulations. The only reason that a municipal council would enact laws for themselves is if they cannot change the standards otherwise.