Triple Gateway Project at Port Authority Terminal, New York City. Lighting design by Leni Schwendinger Light Projects. Photo: Archphoto

Karrie Jacobs

Earlier in this conversation, Leni referred to the class issues related to urban lighting, asking: “Is there a single citizen living in a blighted neighborhood who would prefer less light? Is there a cop or first responder in densely packed modern city who would call for reduced light levels in deference to the darkened night sky?” But Susan, before this conversation began, you sent me statistics suggesting that higher lighting levels do not reduce urban crime. Do you think Leni is mistaken about blighted neighborhoods and first responders?

Susan Harder

We don’t need “extra” light to see well: there are recommended practices issued by the IES that specify the amount of light needed for all applications. There is no reason to exceed those levels. Besides, we really need science behind these recommendations. For example, Chicago officials increased the amount of light in the city’s alleys only to see the crime rate rise. When this was pointed out to the neighborhoods, they still wanted the excess light. . . so education about the problems associated with too much light is needed everywhere.

Leni Schwendinger

You may think me a spoiler — but even recommended levels are changing! Whereas some years ago it was a lighting designer’s best practice to state, “We will meet or exceed IES levels” (and it was understood that exceeding was much better), now people are questioning whether the recommendations are too high, because of energy-saving concerns. And then another camp emphasizes aging eyes and the need for brighter, consistent light and the fact that our U.S. population is disproportionately getting older. Additionally, there is an emergence of lighting-design praxis in Europe that strongly disagrees with the horizontal measurement of light at all and is moving to assert the vertical measurement as more realistic and useful. What happens to the regulations Dark-Sky proposes when the relatively young scientific research of today and maturing design practice of lighting changes?

Harder

As with all laws that are enacted, updates are regularly reviewed by governing boards and approved.

Schwendinger

Certainly education is needed — always. It is generally understood that the perception of safety may be different from the reality presented by crime statistics. But then, crime statistics can be interpreted from different perspectives. (Full disclosure: both my parents are criminologists.) It is true that the eye adjusts to varied levels of light and that the “key” lighting — a relevant film-lighting term — once lowered (and I believe lower light levels overall would be a good thing) and smoothed out on average, will give the impression of “normal.” Once contrasted or compared with a substantially brighter area nearby, however, the lower average brightness area will seem too low or dim.

These cases can be illustrated if need be. I know of a study done in the U.K. that in fact showed reduced crime in relation to lighting. But what I meant in my bold statement was that given the choice, what do you think that people would want?

Harder

That U.K. “study” was completely discredited due to compromised participants. I can give you the names of the people who thoroughly investigated this. In the U.K., there are new reports of reduced crime when some streetlights have been removed or shut off in the middle of the night. I think since we can’t afford to give everyone what they “want” at public expense, we have to base outdoor lighting on what is needed. And “Light pollution has substantial environmental consequences. If any decision is taken to increase lighting, it needs to be taken on the best possible evidence." —British Journal of Criminology (2003)

Schwendinger

I wrote to an urban planner friend in London, who directed me to a 2002 British Home Office survey on the relationship between outdoor lighting and crime and provided some links to interpretations from the press.

My summary of the discussion and quotes is that interdisciplinary, integrated approaches work best. The issue is not mechanistic, for instance, a matter of shielded or unshielded fixtures. And I believe Jane Jacobs’s concept of “eyes on the street” is ultimately important. I have always said that lighting alone does nothing. From the very simplest concept of perceiving light (it cannot be seen except for the presence of material — whether mist or confetti, dust or a building surface) to the more complex issues of urban design and revitalization (a streetlight alone will not affect the environment; it is the road, the building, the park), the whole urban landscape as a composite with lighting is what makes a difference.

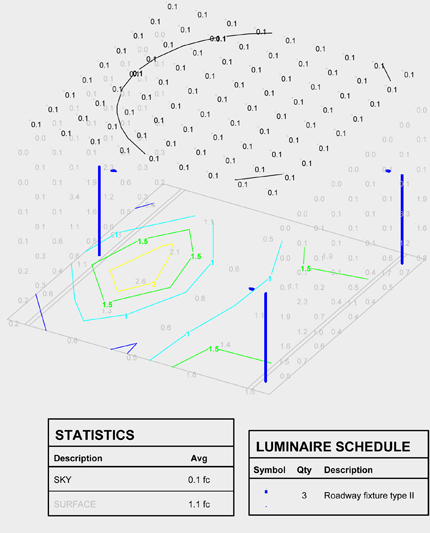

Outdoor Site-Lighting Performance (OSP) is a recent technique invented by Lighting Research Center to help lighting specifiers calculate stray light in the sky. Courtesy Leni Schwendinger

Harder

In a perfect world with lots of expertise available, all of these recommendations would be considered prior to streetlight installations. But I have found that very few, if any, criteria are followed when streetlights are installed. It is usually the result of someone calling and saying, “My street is dark,” and the local councilman calling the town electrician, and a streetlight (whatever is in inventory, and at whatever wattage they have on hand) being installed. It’s really that bad. There are also almost no guidelines to follow, and what is there is ignored. For example, New York State has a warrant for roadway lighting that is based on day/night accident ratios and traffic volume, with some recommendations based on difficult terrain. Politicians, in the name of safety or whatever, secure funds to string up lights even when they do not meet these warrants on state highways.

Schwendinger

In New York City, it is a massive undertaking to get new street lighting — not at all as Susan describes here. In the largest municipalities, the Department of Transportation or Department of Public Works manages street lighting. In the smaller cities, the utilities do.

Harder

The practice is extremely common: in fact, the norm. The federal stimulus funding includes money to add roadway lighting where there was none (and may not even be warranted for safety). We need to weigh the costs and benefits of roadway lighting. In the New York State’s pending “Healthy, Safe and Energy Efficient Outdoor Lighting Act,” there is a provision that no roadway lighting be added unless other means have been examined to meet the purpose of the lighting. With new technologies for reflectors and such, there should be less need for roadway lighting. The entire length of the Long Island Expressway does not meet the New York State Warrants for Roadway Lighting. Also, the New York Thruway (which is a high-speed, high-volume roadway) has no roadway lighting except around the toll areas.

I agree that “light alone does nothing” (including preventing crime).

Jacobs

Is "pollution" the most accurate term for the effect of excessive or poorly designed lighting?

Schwendinger

I do not use the term, except in response to others. I am careful to discern between “light trespass” [spill light cast where it is not wanted], “sky-glow” [brightening of the sky caused by outdoor lighting and natural atmospheric factors] and other terms. This way an exact solution can be offered. Once “pollution” is posited, the cause becomes grand-scale and emotional. Then I wonder how much pollution is caused by which lighting application? What are the percentages? If I replace a post-top will it really help? Or should it be up-lighting, or should we ban neon or perhaps LED billboards, or should we change the reflectivity of roadways so that light doesn’t bounce into the sky? The list is enormous — and I do not yet see the research that really informs us of the worst offenders (for example, I understand that coal plants are above all the worst offenders for air pollution).

Harder

Pollution is an excess of “matter” in an environment; and at this point it is common usage. I only use the term “light pollution” to indicate excessive, misaimed, unshielded or unnecessary night lighting. Not all light can be referred to as “light pollution,” just as all waterways are not polluted

Jacobs

Should I be able to see the stars from my window in Brooklyn, as I can when I'm in Vermont (or even New Jersey)?

Harder

No, but if New York City did not have so many “unshielded” (light emitted upward and off the target) fixtures, yes, you would see more stars than you can see now, though you will never see as many stars, or the Milky Way.

For 20 years, the city of Tucson (population 600,000) has had good outdoor lighting regulations to protect their professional observatories, which ring the city, and you can see a great many stars in the center of the city.

Schwendinger

This is interesting to hear. How many re-shielded lights would it take? What if the lighting target is up — for example 9/11’s Towers of Light memorial? How does seeing the stars in New York City help? (I am not trying to be difficult, just trying to understand the star-gazing issue.) I think it would be great to see the stars wherever we are! I also think it would be great to balance the needs of the urban dweller and the spaces we inhabit with a carefully crafted and considered vision that allows for vibrant cities in all their variety.

I am aware that the International Dark-Sky Association has proposed a zoning system in which dark and bright zones are not assigned within cities but where dark zones are exterior to them. Perhaps Susan can elaborate on that. I think it would be great to have a variety of dark and light zoning conditions — like the park I mentioned outside of Shanghai with great swaths of dark areas as well and more navigable, variously illuminated paths and activity areas.

Harder

I’m referencing “doorway” lighting that is rarely used (rooftop-access doorways), parking-lot lights, streetlights and the types of fixtures that are supposed to be lighting the ground. With respect to reducing light pollution, this would allow city residents to see the stars.

I’m not convinced that the IES/IDA “zone” system for light levels (where they have higher light levels for various tasks based on the population density of a district) produces better vision or a safer environment. Perhaps zones should be assigned to limit total lumen allowances according to the wishes of a community. For example, around observatories or nature preserves, maximum lumens per acre could be useful. Communities need to determine for themselves, through local zoning, the allowances for exterior lighting.

Schwendinger

Yes — and how can we factor in commercial considerations?

Harder

Not sure what you mean by “commercial considerations”? Municipalities regulate commercial

signage to a great degree, and have the same capability for exterior lighting.

Schwendinger

I have created an overview of the urban night that proposes that there are “shades of night” just as there are recognizable time zones in a given day and culture. Zones for a New York day include arriving at work (9–10:00), teatime (11:00) and lunch (12–1:00), through to leaving work at around 5:00. In the same way there are zones of night starting with the after-work drink or get-together through to the nightclub scene.

In my mind, in the future, public lighting will be flexible and active. For example, a main-street organization may work with constituents to decide how to light the night by analyzing the time zones and determining the right lighting levels for the right hours of night depending on usage. An intuitive approach would be to have the brightest setting during restaurant and shops’ open hours and maximum foot traffic. A counter-intuitive approach would be to have public lighting dimmest during open hours as the storefronts, awnings and other illuminated architectural elements provide enough light. But later in the night, after closing, the brighter setting is needed because of a lonely stretch of road for walkers and public-transit riders on the way home.

I am all for developing methods of using light to sustain a more vibrant city — district by district — combining flexible levels of light and other approaches that are also energy-efficient.

I envision a locally based “control center” (I will come up with a better name) that would be a hybrid technological command center cum community center. Here, education about light and dark and public spaces would be available in workshop formats, and guidelines would be set to control public lighting levels for time durations (long term/short term). In a sense, each locale would be its own laboratory for the nighttime environment of that community — whether residential, commercial, mixed use or urban/rural. What I propose here is the best practices of urban design, community outreach and lighting design.

Future setting: Adaptable lighting is available and used. How are the schedules set for evening through dawn use? Although there is general wisdom and guidelines for usage, like micro-climates, there are micro-environments: neighborhoods have local needs, given various diverse populations, levels of business, residential, mixed-use, changing-over-time development and local identity/flavor! I propose that each district should have criteria and a Citizen Advisory Lighting Corps (CALC). The CALC would be composed of a variety of ages and interests and could be an offshoot of a community board, a local council, a business improvement district or a chamber of commerce It could be initiated by a local lighting association or the research/planning division of a university.

Components of the CALC:

1. Education about lighting and the environment

2. A place to hold workshops about development and planning in the area and therefore include lighting as an element of a masterplan

3. The product: A living schedule of lighting control in the area — using shades of night, this group would come up with the best schedule for lights on, lights dimmed, lights off — special lighting (holidays for example). By “living,” I mean that the schedule can be instituted with a review period and changed if needed.

Jacobs

My sense is that that both of you agree that bad or excessive lighting has an adverse impact on the environment: trees, birds, humans, etc., but that Susan would like to address the excesses through regulatory mechanisms, while Leni is concerned that overly broad regulations will not just ban bad fixtures but also good ones, inhibiting creativity and innovation.

Harder

I’ve never recommended “overly broad regulations.” I’m recommending regulations that address utilitarian lighting. There would be no constraints on creativity and innovation. There is no conflict between Leni and me on this issue.

When I was in London recently, I saw the very best city streetlights that I have ever seen: they were full cutoff (no light emitted above the fixture) and they emitted an incandescent color (more full-spectrum) light. The effect was extremely pleasant, rendering the buildings quite beautiful, and there was a psychological “restful” feeling. I felt safe (studies show that glare makes people feel less safe than non-glare lighting) and comfortable. The bulb appeared to be long, like High Pressure Sodium (HPS). You could see a “cut off” of the light on the third floor of the adjacent residential buildings, not emitting light into residences. From what I can gather, these streetlights were changed when the London engineers responded to the local dark-sky advocates who had sponsored a conference on better lighting.

Clearly, the technologies are available for better lighting. I think that the best way to achieve that goal is through public education and municipal regulations to assure compliance.

Schwendinger

Here are my priority objectives in relation to the way that lighting affects the environment

1. Illumination will be recognized by the AEC industry, government and general public as an integral and important element of all public-space design. Therefore, fair budgets will be available to do a good job.

2. Planning departments will share responsibility with departments of transportation to determine guidelines and best practices for cities to integrate lighting programs into planning practice (i.e., lighting to be included in early phase masterplans).

3. Funding will be available for interdisciplinary research — for example, to analyze and evaluate light’s effect on health, social issues (public interaction, crime, etc), economic development (foot traffic, tourism, etc) — and think tanks for solutions.

4. Software and hardware solutions for adaptable lighting will be underwritten so that cities can easily install state-of-the art control systems to gain mastery over their nighttime environment. Community involvement programs will be part of the adaptable lighting approach — for example a Citizen Advisory Lighting Corps (CALC) will be assembled to develop "living control plans" for their district.

5. Lighting regulations will be firm enough to provide criteria for good lighting design and to avoid light trespass and sky-glow. Energy-saving objectives will be set, with flexibility as to how these objectives might be met. However, restrictions will not preclude lighting design that may "go against the grain" yet, in spirit, fit the objectives stated. Exemptions may be one way to allow for exceptional design.

Harder

Here are my priorities for outdoor lighting regulations:

1. All new outdoor lighting (municipal, commercial, residential and for special-permit events) needs to be reviewed by a governing agency prior to installation to assure compliance with community standards. The submissions need to include information about fixture light distribution type, lumen maximum, bulb type, mounting height and location and anticipated hours of use.

2. As is desired by a community, and as is financially feasible, regulations need to be enacted to address issues related to light trespass and glare intruding on private properties, much like local zoning codes for noise complaints.

3. Municipalities need to adopt standards for lighting in the right-of-way (for instance, street-lighting and walkways) so that fixtures direct the light toward the public areas, in the correct amount of light, and are adjusted or turned off when use is completed.

4. Lighting needs to take into account the character of the areas and to protect flora and fauna from the negative effects of night lighting and sky-glow wherever appropriate and desirable.

5. Lighting regulations need to be reviewed as technologies improve and as evidence is presented as to the effects of lighting on human health, flora and fauna.

6. Public education campaigns need to be promoted and readily available and, as necessary, updated.

7. Where a community has made a decision to protect certain areas for astronomical observations, greater care needs to be taken to address the special needs of astronomers to reduce sky-glow.

Jacobs

I guess in an ideal world, whether it’s Susan’s world or Leni’s, everyone would pay more attention to the impact of their lighting decisions. And the message here is that lighting should never be treated as an afterthought, but as an integral part of any design project, whether we’re talking about a highway, a parking lot or a spectacular urban building or public space. I’m want to thank Susan Harder and Leni Schwendinger for leading us, however unexpectedly, to consensus.