Note: On March 12, 2020, SVA NYC planned to host “Archives By Design,” a symposium featuring representatives of six design and illustration archives, moderated by me and Beth Kleber, Founding Archivist of the Milton Glaser Design Study Center and Archives and the School of Visual Arts Archives, New York City. Featured speakers were to be Rob Saunders, Executive Director, Curator and Publisher of Letterform Archive; Jennifer Whitlock, Archivist, Vignelli Center for Design Studies at Rochester Institute of Technology; D.B. Dowd, Faculty Director, D.B. Dowd Modern Graphic History Library at Washington University, St. Louis; Jeanne Swadosh, Associate Archivist for the New School Archives and Special Collections, which includes the Kellen Design Archives of Parsons School of Design; Alexander Tochilovsky, Curator of the Herb Lubalin Study Center of Design and Typography at Cooper Union.

The precautions initiated by the spread of the coronavirus forced the cancelation for now, with the hope that by Fall the crisis will have subsided enough to reschedule. In the meantime, below are my introductory comments.

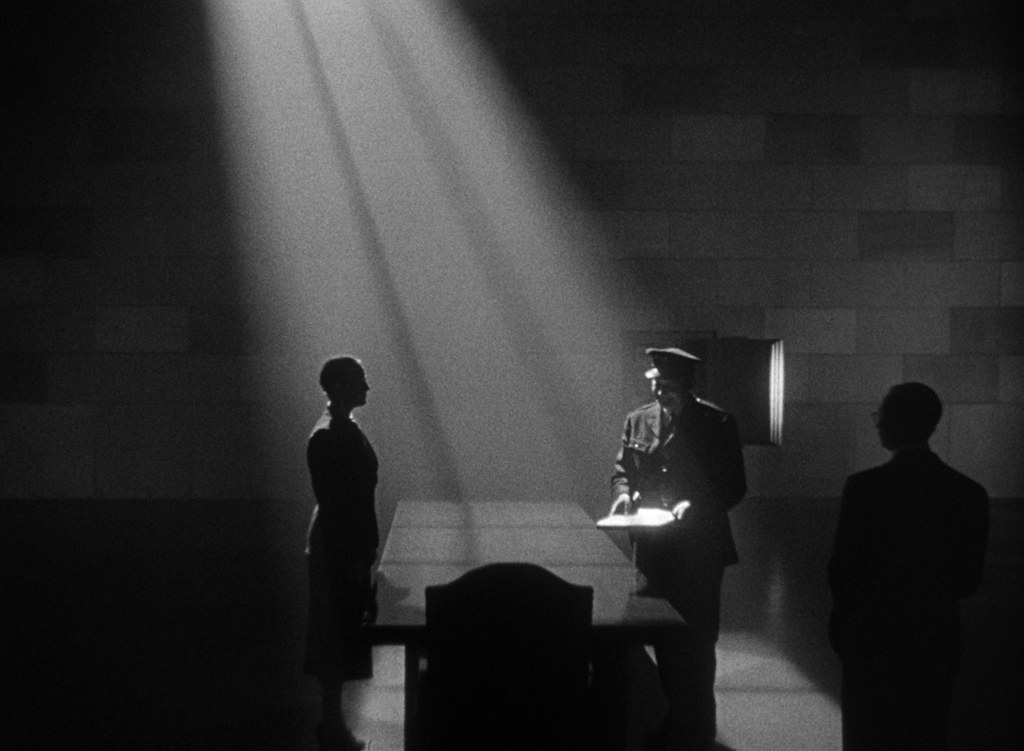

This scene from Citizen Kane is one way to think of an archive. Yet archives, and especially graphic design and illustration archives, come in many formats and configurations.

An archive is a cataloged collection of past and present accomplishments that is organized (or disorganized) in different ways for numerous purposes including scholarship, reference, and preservation. Archives can be public, private, personal, institutional, professional, and cultural. They are wellsprings of history — repositories of the past and present as resource for the future.

Archives are however, more than warehouses, they are greenhouses for the nurturing of narratives. Out of archival seeds mighty stories grow.

Many of them exist or are currently in the making. Many designers and illustrators who have made contributions to the visual culture and communications media are building archival foundations. Herein lies a problem: there is limited space to house and even fewer experts and erstwhile amateurs to maintain these repositories as they should be maintained. Therefore, regardless of who or what comprises a specific archive they cannot contain everything an individual, studio or firm has ever produced.

Since the necessary resources are lacking, who decides what or who deserves preservation? It takes commitment and vision to divine what will make the cut — and sometimes, wrong decisions are made. How often has valuable material been mistaken for inconsequential junk? What is extraneous is sometimes essential and vice versa.

A proper archivist is, in fact, a prospector who pans for archival gold then filters it for valuable raw material that scholars can interpret, shape and transform into stories. Archivists rigorously search not just for physical artifacts but for the plans, notes and iterations behind the work. In every bag or box, envelope or file, there’s no greater satisfaction than when an archivist finds that there’s “gold in them there hills.” And that gold can be on moldy paper or pristine files.

One person’s posterity is another’s garbage. Printing and type samples, even when saved by their producers or creators as records of work, are not always preserved for long-term posterity. There comes a time where the output of an individual’s, studio’s or business’s work exceeds the ability to contain and catalog the artifacts that they’ve produced. The question of what to keep, what to dump and, more important, what to archive is a day of reckoning.

This symposium, “Archives by Design,” organized by my colleague Beth Kleber and myself, with enthusiastic support of David Rhodes, president of the School of Visual Arts, is conceived to address the increasing needs to 1. Preserve the histories of graphic design and illustration in all its varied manifestations and 2. Determine who, how, and why certain artifacts are deserving of preservation in an archival environment.

Not surprisingly, as design and illustration have become more integral to the writing, teaching, and understanding of history in general, and has developed into its own history, archives are growing in number. Some are independently operated others are folded into educational facilities. Archives are also burgeoning with the passing and aging of generations who are ready to release their work to for scholarly and public use. In fact, the large number of practitioners finding permanently accessible homes for a growing number of legacies is far exceeding the ability to accept them.

As design history becomes more relevant, it is important that archives and archivists do this crucial job, including determining the criteria for selection, methods of preservation, financial sustainability, the goals, long and short term, and how they are making accessible the work in their respective audiences.

Active Archive Urls:

https://archives.sva.edu/

http://lubalincenter.cooper.edu/

https://guides.library.newschool.edu/kellen_fashion_design

https://www.rit.edu/vignellicenter/

https://library.wustl.edu/spec/mghl/

http://www.artcenter.edu/academics/interdisciplinary-programs/hoffmitz-milken-center-for-typography.html

http://peoplesgraphicdesignarchive.org/

http://peoplesgraphicdesignarchive.org/