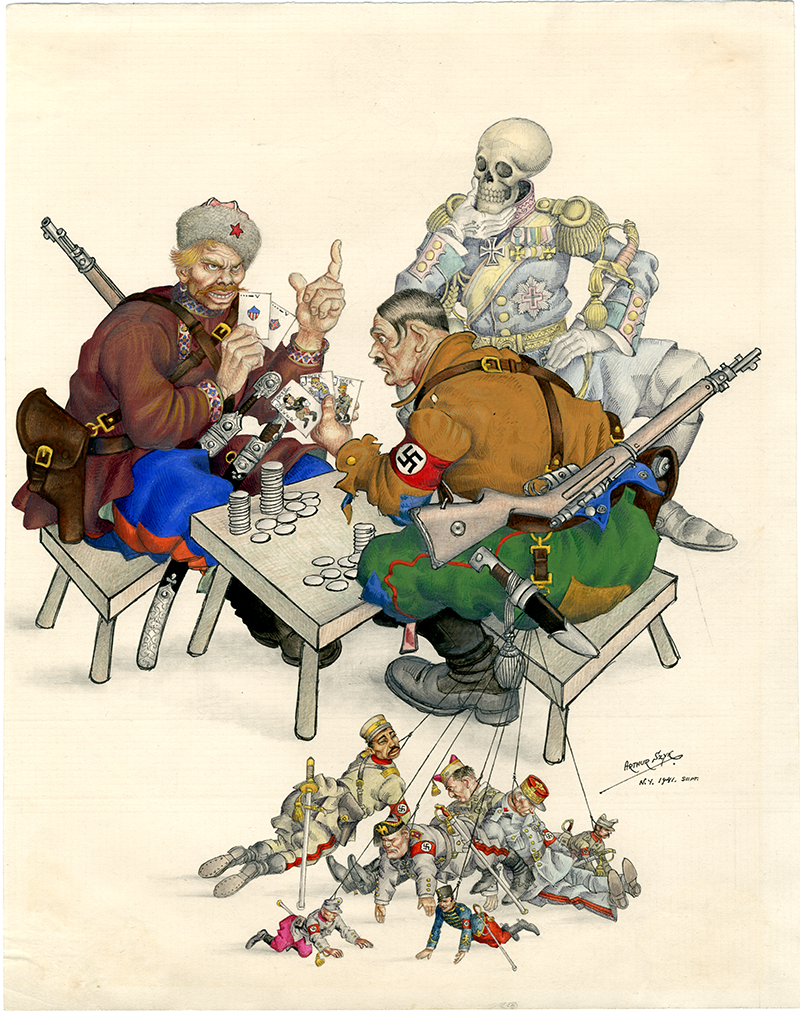

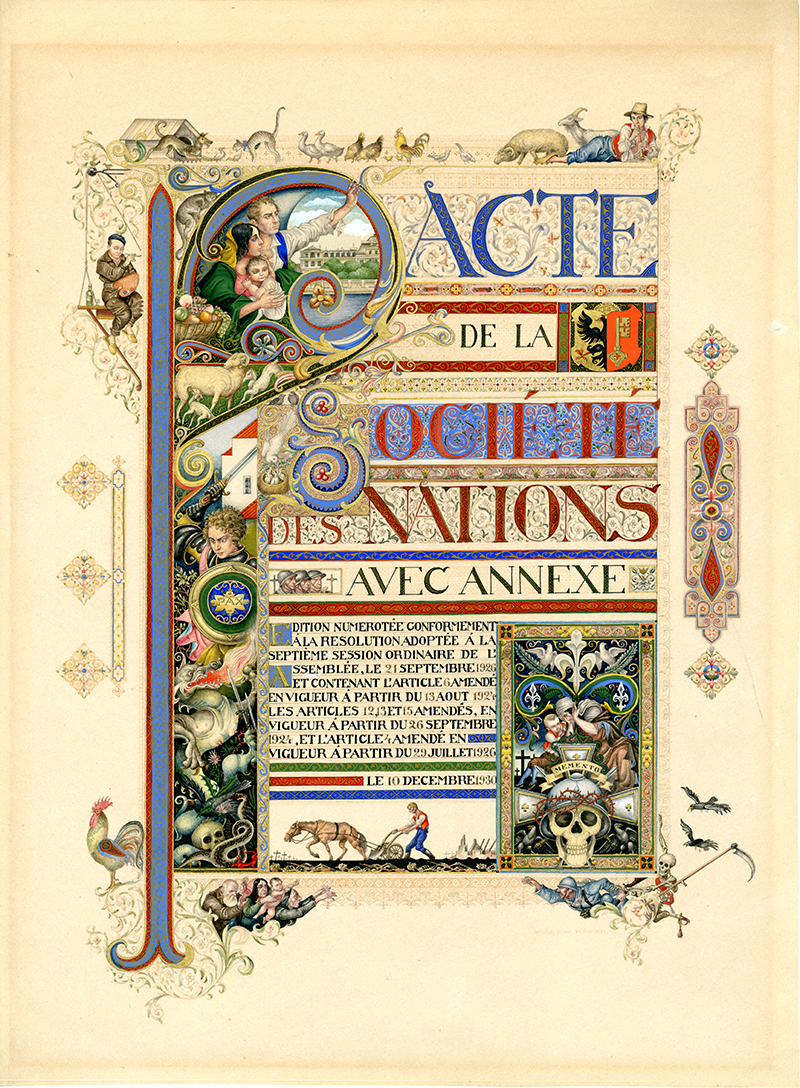

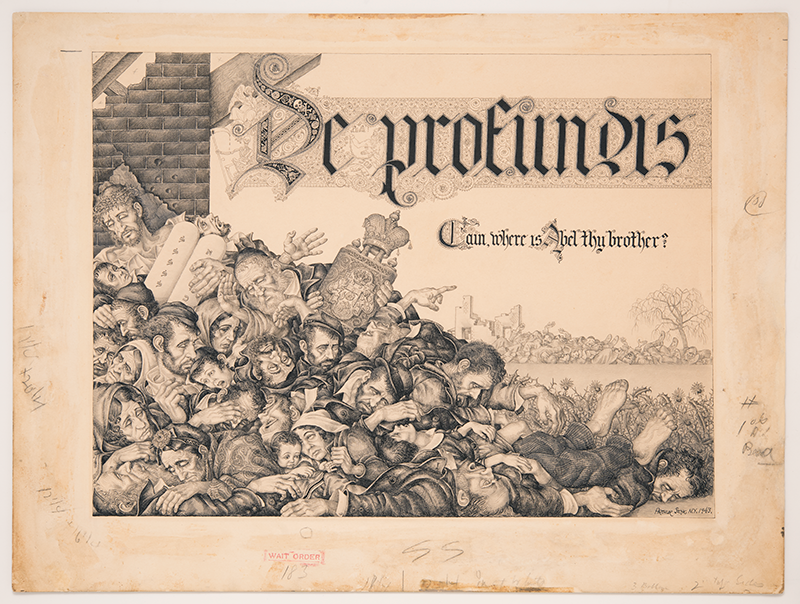

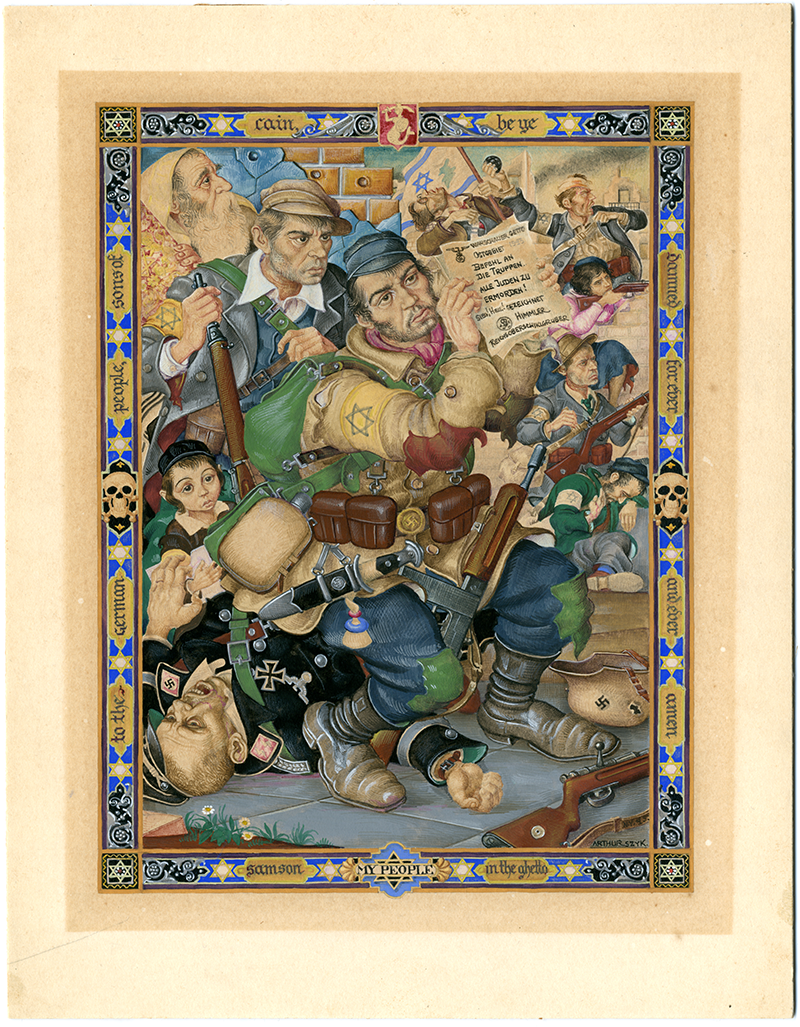

The Polish émigré, American caricaturist and illustrator, Arthur Szyk (pronounced schick, like the razor) (1894–1951), began his career in 1914; he illustrated over 30 books, created scores of caricatures and portraits as covers for Colliers and Time magazines, numerous cartoons for PM (the 1940s ad-free liberal/left daily), the New York Post, and Esquire, as well as posters, medallions, stained glass, and a large body of work on Judaic themes. One of the most prolific visual satirists of his day, his World War II anti-fascist imagery is comparable to Goya’s Disasters of War, but his mission went beyond topical satire — art was an engine of spiritual transcendence. A victim of anti-Semitism in his native country, forced to move to Paris, England, and later the U.S., he fought for a free Polish state as both soldier and artist, and later devoted his energies helping to build a Jewish state. Indeed almost all his art, including numerous books of illustrated fairy tales, were imbued with appeals for social justice. “To call Szyk a ‘cartoonist’ is tantamount to calling Rembrandt a dauber or Chippendale a carpenter,” declared an editorial in a 1942 Esquire. In fact, with articles about him published in The New Yorker and the New York Herald Tribune, among others, his artistic renown was undisputable. Szyk was one of the first public figures to take direct action in bringing attention to the Holocaust as it was being perpetrated. The intricate, miniature size of his artwork stands in striking juxtaposition to the magnitude of the themes it confronted and the human rights violations it exposed. Yet time has a way of eroding memory, and Szyk’s art had receded into the past until a major revival was triggered by Irvin Ungar, who created a foundation in Szyk’s name, organized exhibitions, published books and preserved work that had scattered throughout the world. Two years ago he sold this extensive collection to the Bay-Area based Taube Philanthropies, which is committed to making Szyk’s art relevant given that he covered many of the same issues of human rights facing us today. (The Taube Family Arthur Szyk Collection is owned by The Magnes. Taube Philanthropies gave the largest monetary gift to acquire art in UC Berkeley’s history to The Magnes to support the collection three years ago.) Currently, an exhibition at University of California, Berkeley is bringing Szyk’s works to contemporary audiences. In Real Times. Arthur Szyk: Art & Human Rights (1926-1951) that opened on January 28 until May 29 and resumes September 1 to December 18, 2020 is on view at The Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life at UC Berkeley. The new exhibition from the Taube Family includes more than 50 original artworks by Szyk and features two interactive workstations created by UC Berkeley students and Francesco Spagnolo, Curator of The Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life at UC Berkeley.

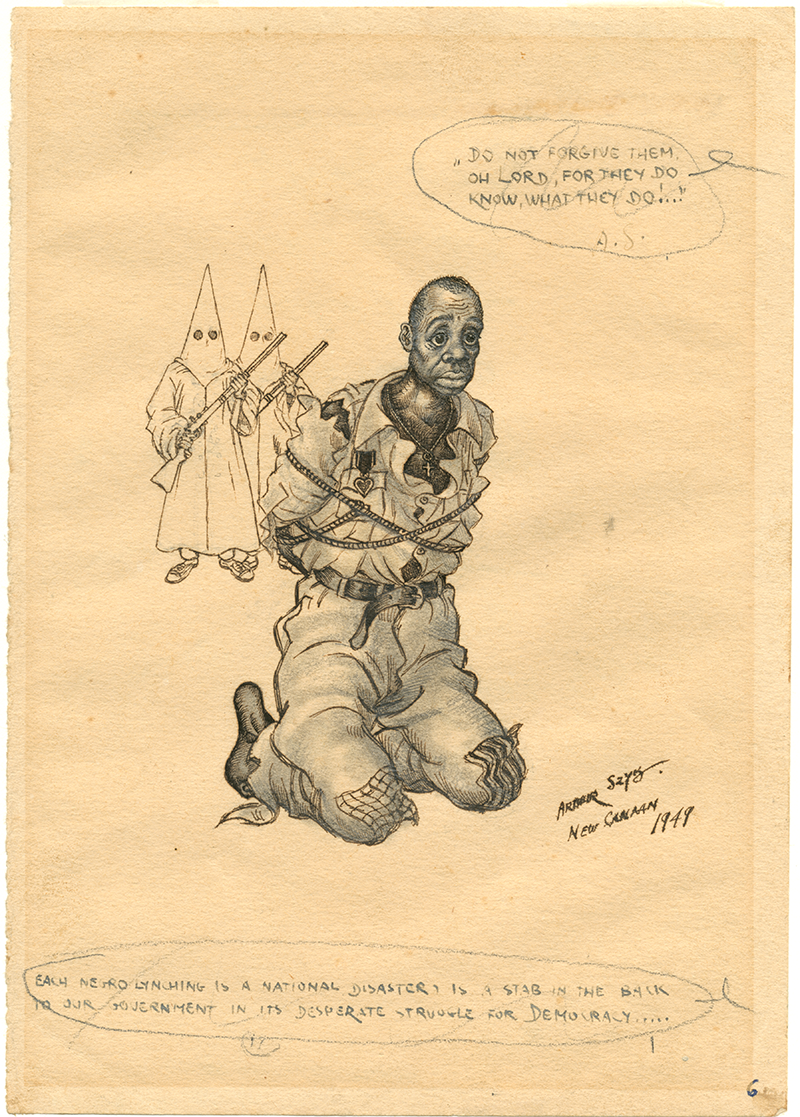

As part of the exhibit UC Berkeley students digitized the entire Taube Family Arthur Szyk Collection of more than 450 pieces for the workstation titled “The Artist’s Gaze, Through a Digital Lens,” which presents each image in a high-resolution slideshow. Szyk addressed a diverse range of subjects including the U.S. War of Independence, the Holocaust, World War II and the Ku Klux Klan. Visitors can pause the slideshow and zoom in on any image to reveal unexpected details and extraordinary craftsmanship. For an innovative feature of the exhibit, the “Arthur Szyk, Remixed” workstation, students deconstructed more than fifty of Szyk’s works allowing visitors to examine the characters and motifs individually and then recombine them to make their own political cartoons. New creations can be saved and instantly published online, giving Szyk’s art an even wider audience. The screens of both workstation tablets are projected onto the walls of the gallery for all to see. The works are organized into six sections focused on various aspects of human rights:

• Human Rights and their Collapse is an introduction to Szyk’s world with a timeline showing his life in the context of the progressive failure of European democracies and the human rights and national rights movements, beginning with the American Revolution. Syzk’s works begin to show his lifelong focus on freedom and the dangers of tyranny and totalitarianism.

• The Rights of Global Refugees shows Szyk’s deep concern for refugees like himself and their lack of the legal protections of citizenship. This section features depictions of refugees in many contexts, from cartoons of innocent children declared enemies of Third Reich to biblical narratives and a self-portrait included in Szyk’s ode to Canada.

• The Right to Resist highlights the role of resistance in preserving human rights with Szyk’s paintings of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising and his internationally acclaimed illustration of “The Statute of Kalisz.” The statute, which granted Jews legal rights and liberties in Poland in medieval times, was displayed in London in 1933 to denounce antisemitism in Nazi Germany.

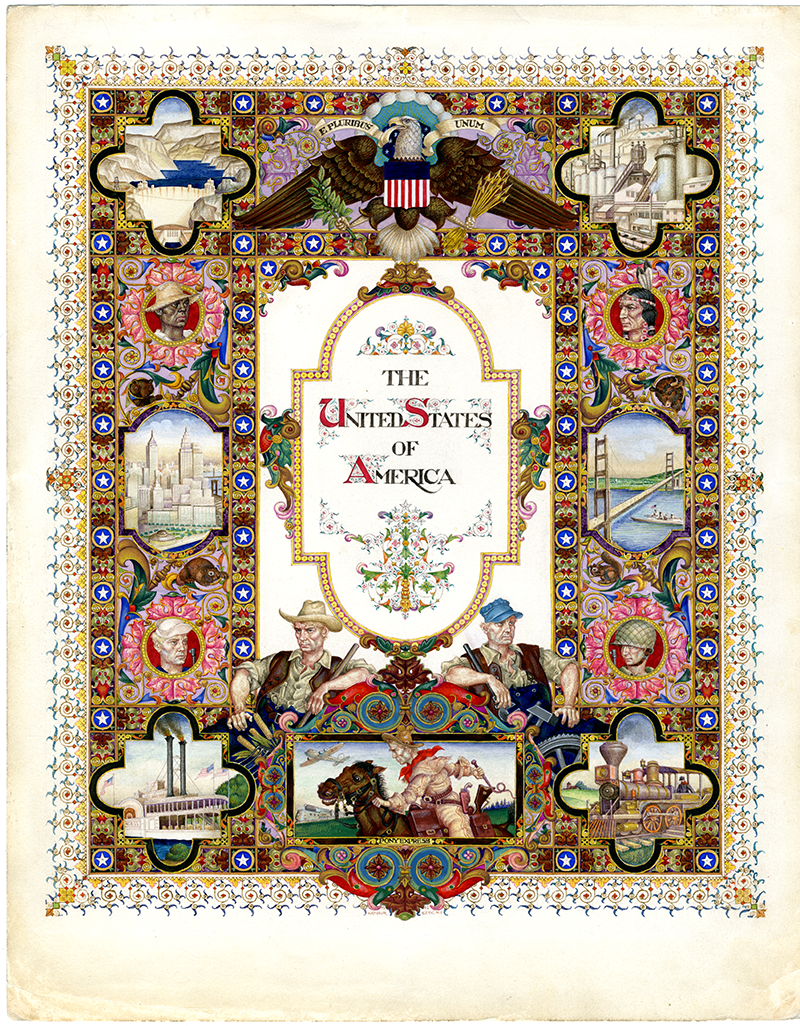

• The Rights of Nationhood further explores Szyk’s belief that human rights are inextricably tied to citizenship, featuring designs he created for countries and organizations. These detailed illustrations became letterheads and stamps and often found their way into his political cartoons.

• The Right to Expose: Executioners at Work displays many of Szyk’s most powerful pieces, which depicted the crimes of Axis leaders and Nazis during the Holocaust. This portion of the exhibition also explores an interesting parallel to Charlie Chaplin’s characters in his 1940 movie, The Great Dictator.

• The Right to America highlights Szyk’s appreciation of his new home country and the multi-ethnic fabric of the U.S. Army, positioning it in direct contrast to Nazi Aryan supremacy. The work in this section reflects Szyk’s objection to racial discrimination and the organizations that perpetuate it, such as the Ku Klux Klan.

Sadly, these themes are still gnawing at the body politic, and what is more, they are resurging in many parts of the world, including the United States. So, when I heard about the enterprise, I asked Dr. Spagnolo to discuss why Szyk’s art continues to spark emotions and how best this can be harnessed as resistance to forces that he was resisting decades ago.

Steven Heller: What prompted the Szyk exhibition now? Is it motivated by the increasing revival of fascism in Europe and elsewhere?

Dr. Francesco Spagnolo: The exhibition is the result of three years of work with the Taube Family Arthur Szyk Collection. This involved a comprehensive cataloging effort (aimed at establishing historically correct titles, creation dates and places, and exhibition history dating back to Arthur Szyk’s lifetime), along with the digitization of close to 450 original artworks.

One of the themes that emerged from this cataloging work is the artist’s ongoing concern with global human rights. This is a theme that continues to be current. The fact that most of Szyk’s production happened during the collapse of European democracies (ca. 1920-1939), the rise of Fascist regimes, the Holocaust, and the aftermath of World War II, was a particularly poignant aspect that inspired the exhibition's narrative.

The exhibition seeks to establish the cultural context of Szyk’s concerns, drawing direct parallels with contemporary artists and thinkers such as Charlie Chaplin and Hannah Arendt. It also draws from recent research on the role of East European Jewish intellectuals in framing the legislative context of global human rights after the Holocaust (specifically a recent volume by James Loeffler, titled “Rooted Cosmopolitans”).

The echo in today’s global crisis of democracy is definitely part of why we believe this exhibition to be relevant at this time.

SH: The UC Berkeley students have added an interactive component to the human rights exhibition at The Magnes. How did this come about and what exactly does this addition entail?

FS: The impetus for the digital component of the exhibition is the result of my ongoing collaboration with the “Digital Humanities” community, on the UC Berkeley campus and beyond. The “digital lens” aims both at reconstructing the artist’s gaze on his own, often miniature-sized, artwork, and at providing new tools to study and confront Szyk’s aesthetics (especially its modularity) through a deep immersion into his techniques and artistic choices.

The results of this work, which is part of my instructional offerings at UC Berkeley, are hopefully highlighted in the exhibition installation itself. The installation (along with the user interactions it elicits) is currently being studied by UC Berkeley students in my undergraduate research group and Graduate Seminar. In other words, the exhibition is already providing materials to future research and teaching projects.

SH:I presume the students were not well aware of Szyk’s work, no less his place in time. How did they respond to the work in terms of their current lives?

FS: Concerns for global human rights, the social role of the arts and humanities, and for the future of memory are widespread among UC Berkeley’s students. While they were not familiar with Szyk’s work, the digital investigation led them to become intimately familiar with it. We also discussed the emotional impact this work elicits, and how to manage the feelings that proximity with so many historically and socially charged images and the glaring violations of human rights they exposed and depicted causes in young students.

SH: What are they hoping to inspire in the audience for this exhibition?

FS: They are hoping to inspire a broader understanding of Szyk’s work, and of its context. The role of the arts in confronting global political events. The importance of global human rights in our times, 100 years since the start of WW2 and 75 since its end. The realization that tyrants never act alone, and that art can stimulate social response to the violation of human rights.

SH: What has been the response to Szyk’s work and do viewers understand its relevance today?

FS: The exhibition has been open for less than two weeks. Between individual visitors and classes, we’ve had approximately 300 visitors during this time. A couple of my students and I have been in the gallery when it is open to try to assess the initial visitor response. We have observed that visitors tend to be:

- Amazed ("wow factor") by the large digital slideshow

- Captivated by the individual artworks on the gallery walls (they tend to spend sufficient time trying to decipher them—which is understandable, given their miniature size)

- Willing to "play" with the workstation that allows one to create new art based on digitally cropped elements from Szyk's original works

- A few visitors were taking photos of themselves in front of the slideshow projection, sort of "immersed" in the projection itself (this was an unexpected, and welcome, response).

This current exhibition (and doubtless more to follow), while not the same, is reminiscent of Pablo Picasso’s wish that his most famous anti-war painting, Guernica , be returned to Spain after the death of Fascist dictator Francisco Franco and hung in the annex of the Prado museum in Madrid so that the Spanish people could bask in its visual and emotional energy. Szyk, you might say, produced many small Guernica’s and while none were as monumental, they have the power to inspire. Until Ungar began his mission to revive them, time had obscured their collective impact. This exhibition and the interactive experience it influences brings the work out from the shadows, re-energized to help viewers better address the difficult social, political and environmental battles being waged today.