Cover of Aim for a Job in Graphic Design/Art by S. Neil Fujita

Aim was written, after all, in a period of cultural flux, when anti-establishment behavior was fashionable and graphic design was split between competing aesthetics. On one side, less-is-more modernism had overtaken the corporate world. On the other, florid decoration was being channeled into mass media through the radical youth culture. Fujita’s book, although visually understated — colorless yet clean — was written for an audience bombarded by the era’s flamboyance.

The book focused on teaching high school seniors the fundamentals of graphic and advertising design. Fujita, director of design and packaging for Columbia Records in the late 1950s and president of the design firm Ruder, Finn & Fujita, was well suited to introduce students to print design. The creator of now iconic book jackets for Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood and Mario Puzo’s The Godfather (with its famous puppeteer image), as well as scores of record album covers that introduced abstract expressionist art to music packaging, he understood the need to push limits.

“We should never forget the kind of person we want in design,” Fujita wrote. “People with fresh viewpoints, fresh ideas, fresh concepts of the reality we all seek. We may find them right here in our high schools. We must let you students express your ideas of the reality that concerns us all.” Inspiring words, except that Fujita’s “reality” remained at odds with the freaky styles of the times. The book made no real effort to connect to people, like me, who were experimenting with art and design in various media, including fashion. I found myself chuckling at the section “Your Appearance,” where Fujita wrote: “An interview does not depend solely on your portfolio. The impression you make depends on two factors: the portfolio and yourself — how you speak and how you look. In general, it is better to be a little conservative in the way you dress for your job interview. On that particular day, concentrate your originality in your portfolio and not in your clothes.”

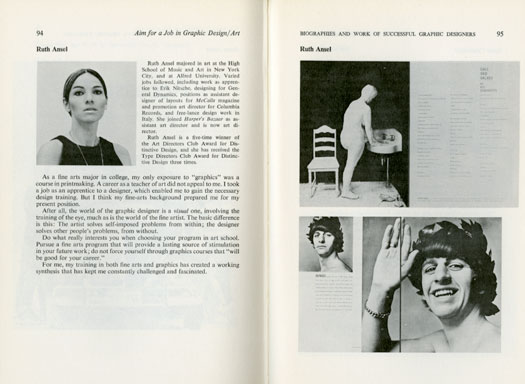

Fujita’s definition of successful graphic designers fits his idea of fresh viewpoints that flourished in a corporate environment. Of the dozen professionals that earned that distinction and whose biographies were featured in the book, three are still known today: Ruth Ansel, then co-art director of Harper’s Bazaar; Louis Dorfsman, the brash CBS art director; and George Lois, the legendary ad man. Unknown even to me are Peter Adler of Adler, Schwartz Inc., who worked at CBS and ran an advertising agency; Janet Czarnetzki, a Columbia Records alumna and art director at American Heritage books; Sheila Green, an art director at Doyle Dane Bernbach; and Arnie Lewis, who ran Pavey Jones Lewis. But all four won major Art Directors Club awards for work emblematic of the “Big Idea” school (photographic, conceptual and witty).

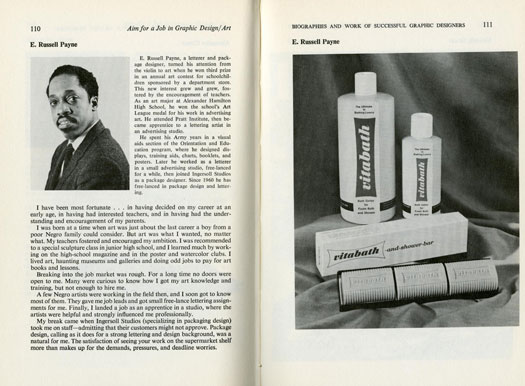

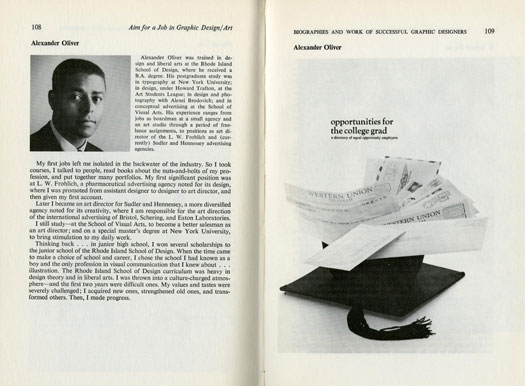

The book takes a more radical turn, however, with profiles of two African Americans: Alexander Oliver, a Rhode Island School of Design grad with a master’s degree in typography from New York University, who worked as an art director for the ad agency Sudler & Hennessey; and E. Russell Payne, a packaging designer who created the Vitabath package still used today. Their comments, directed at aspiring designers, are sobering reminders of the era’s racism: “Breaking into the job market was rough,” observed Payne. “For a long time no doors were open to me. Many were curious to know how I got my art knowledge and training, but not enough to hire me.… A few Negro artists were working in the field then, and I soon got to know all of them. They gave me job leads and got small free-lance lettering assignments for me.… My break came when Ingersoll Studios took me on staff — admitting that their customers may not approve.”

Oliver said, “My first jobs left me isolated in the backwater of the industry. So I took courses [at the School of Visuals Arts], I talked to people, read books about the nuts-and-bolts of my profession, and put together many portfolios.” At RISD, “My values and tastes were severely challenged; I acquired new ones, strengthened old ones, and transformed others.”

Spread of Aim for a Job in Graphic Design/Art featuring E. Russell Payne

Spread of Aim for a Job in Graphic Design/Art featuring E. Russell Payne Spread featuring Alexander Oliver

Spread featuring Alexander Oliver

Spread featuring Ruth Ansel

Fujita, a Hawaiian of Japanese ancestry, who in 1942 was sent to a Japanese internment camp in Wyoming, was sensitive to the difficulties minorities experienced in the design field. His decision to include African Americans was doubtless pragmatic, since the high schoolers he was addressing in 1968 were more diverse than previous generations. Although his book does not dwell on the subject of race, it reveals an effort to open doors to all aspirants.

Fujita presents graphic design as a viable creative career. But he was also conscious that it was a young profession, still forming an identity. “The graphic shape of every civilization is the product of the designer’s eye,” he wrote. “For it is the designer who translates the visual insights of his age into the patterns of everyday life.” Ruefully, he noted, this value has been scarcely appreciated, and the designer has come “to be looked at by many as little more than a workman.”

He sought to correct that “workman” perception by focusing on design’s conceptual over its technical aspects. In emphasizing the need to impress business and industrial leaders, he devoted considerable attention to education — describing, for instance, how Oliver “designed” his own master’s degree at NYU.

Yet far from extolling the analytical, Fujita turned the other way, to a celebration of feeling that certainly fit the era’s appreciation of intense sensory experience: “Too many of us have become terribly insensitive to the things we touch, smell, taste, hear and see,” he wrote. “We have forgotten how to feel, and so we take the next best avenue of approach to living. We intellectualize the things we have failed to grasp with our sense. We have developed aesthetic theories only to discover with dismay that it was foolish to start because so many such theories have appeared…just to disappear in the mist of passing days. And when you ask yourself, ‘what exactly is meant by ‘aesthetics’? the word becomes thinner until finally its sounds hollow and empty.”

Instead of practicing theoretical exercises, he urged, “Let’s dig into things and search for what we personally feel is truth. Not truth in relation to accuracy manifested in acts and comprehended by feelings. As communicators, we should be the spokesmen of this truth…only then will we be able to make our efforts in print worthwhile to others.”