Photograph by Robert Lyon, courtesy of Daniel Friese

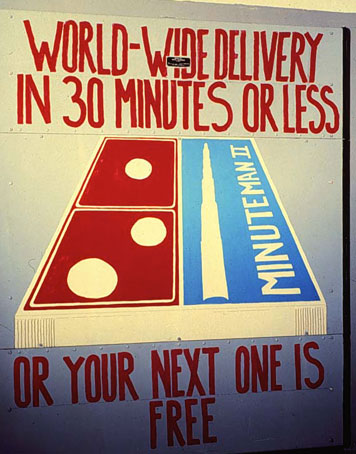

At the back of what looks like an enclosed porch of an unpretentious ranch house near Wall, South Dakota, a steel-runged ladder leads down a 30-foot concrete access shaft. At the bottom, a massive, eight-ton steel-and-concrete door is painted the red, white and blue image of a Domino’s Pizza box, with a slightly altered phrasing of the chain’s familiar promise: “World-wide Delivery in 30 Minutes or Less; Or Your Next One is Free.” But in this case the “Next One” is a Minuteman II intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM). For almost three decades, the house was the “Delta One” Launch Control Facility (LCF) for ten Minuteman missiles armed with nuclear warheads. The massive blast door was designed to ensure that the underground launch control center survived a nuclear attack.

Welcome to the mordant, jingoistic and occasionally crude — but rarely before seen world — of “blast-door art.”

| Play Slideshow >> |

Like the garish and cheeky illustrations etched across the noses of World War II aircraft, these images in launch control centers across the United States testify to the bravado of the men (and, from the mid-1980s onward, women) of what has been called “America’s Underground Air Force.” But they also reflect the sometimes surreal pressures faced by two-person missile crews on 24-hour duty alerts, waiting for a call to turn their missile launch keys and perhaps end civilization as we know it. “You’re sitting there waiting for the message you hope never comes,” says Tony Gatlin, who painted the Domino’s homage as a young deputy flight commander at Delta One in 1989. “That’s a pretty screwed up way of looking at the world.”

Now an Air Force major and deputy director of staff with the 100th Air Refueling Wing, based at the Royal Air Force’s Mildenhall Base, in England, Gatlin was struck by the similarity of Domino’s delivery time and that of his missiles. “One went with the other kind of well,” he deadpans. Gatlin’s painting is one of only a few the public can see, following the transformation in 1999 of the Delta One control facility and the nearby Delta Nine missile silo into an historic site by the National Park Service (NPS). Under the terms of the 1991 Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty between the then-Soviet Union and the United States, many Minuteman missile sites have been deactivated or destroyed.

Photograph by Robert Lyon, courtesy of Daniel Friese

“The site is an exceptionally important icon from the Cold War era,” says Greg Kendrick, the NPS historian who led the effort to conserve it. He calls the decorated doors “imaginative and amusing artwork.” Though plenty of painted blast doors remain at missile bases in North Dakota, Montana and Wyoming (where some 500 Minuteman III missiles are still on alert), would-be aficionados can’t exactly wander in unannounced. It is thanks to Daniel Friese, a civilian employee at the Air Force Center for Environmental Excellence, in Brooks City-Base, Texas, that a visual record of the doors exists. Friese, who was in charge of cultural resources at Ellsworth Air Force base in South Dakota from 1993 to 1997, was a fan of Gatlin’s Domino’s knockoff. “We’d get to talking to the missile folks and they’d say, ‘Oh yeah, Delta One’s not the only one that has artwork — you should see the one at Foxtrot [another LCF],’” he says. “That’s what gave me the idea.”

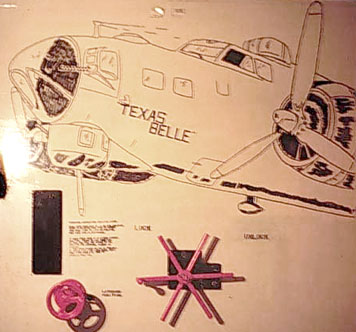

In 1995, he got a grant from the Department of Defense and, with photographer Robert Lyon, set out to capture this subterranean culture. “It was the greatest four weeks of my life, going to all these holes in the ground,” says Friese, who was trained as an entomologist. He estimates he has nearly 400 images from about 100 launch control facilities across the central and western United States, and is an authority on the genre. At Whiteman, for example, several cartoon characters (e.g., Road Runner, Oscar the Grouch) showed up, but so too did the squadron’s predecessor nose art. “They had taken a lot of the art from their B-17 squadron, the host squadron. That was a little different from Ellsworth, which was a little more freeform, if you will.” On several blast doors in the Whiteman squadrons, the actual B-17 is itself depicted; painted above the cranking mechanisms and the warnings to “Stand Clear of Door,” they bear replicas of the original nose art, with logos like “Texas Belle” or “Piccadilly Commando.” The latter, notes Friese, refers to World War II serviceman’s slang for the women who used to solicit in Piccadilly Square; the phrase “30 Bob,” also found on the blast door art, referred to the going rate.

The images in Friese’s collection are a jumble of regimental markings, cartoon character references (everything from Calvin and Hobbes to Captain America), and outright martial bravado. “There just seems to be a propensity for warriors to either mark their weapons or their territory,” says Friese. “Or it’s just boredom.” Striking too is the dark undercurrent of some of the artworks, skull-and-bones depictions or a grim reaper looming over the capsule entrance, scythe in one hand, missile in the other. “It was gallows humor,” says Friese. “It was like, ‘Hey, we’re defending the free world, and we don’t fear the commies. If it’s going to happen it’s going to happen, and we’re here to finish the job.’ I think that was the whole Cold War mentality.”

For previous generations of Minuteman crews, blast-door art might have seemed like something of a luxury. William Huey, a missileer at Whiteman during the 1960s, noted that blast-door art was an alien concept during his tour, the post-Cuban Missile Crisis days in which missileers still wore launch keys around their necks. “We had zero, zilch, nada door art, coats of arms, insignia at any site where I ever pulled alert. We had nothing but ‘Eye-Ease green paint’ as far as you could see, anywhere from the above-ground LCF to the underground equipment building and Launch Control Center.”

Even when it was allowed, blast-door art was rarely permanent. “There were times when commanders would go down there and say, ‘get rid of this stuff,’ when they didn’t want to see anything on the wall except official signs,” says Friese. When Brooke returned to Malmstrom recently for a reunion most of the artwork had been painted over, save for a single dog, now hidden behind some reconfigured equipment racks.

From the perspective of the “crew dogs” who pulled the 24-hour alerts, the artwork was a way to build morale for a job marked by routine, isolation, and fleeting episodes of very high anxiety. Missileers, after all, sat at the controls for missiles with megaton-range payloads, more than a dozen times more powerful than the bomb dropped on Hiroshima, aimed at strategic targets or population centers across the Polar Cap in the Soviet Union. (Gatlin still will not reveal his classified targets). The job was paradoxical: To perform successfully the real job that they were trained for — launching missiles — would in all likelihood mean they would never again see daylight. As Gatlin explains, “You’re doing a job that you hope you never have to do."

The images help us understand how the missile crews “handled a power that was capable of killing hundreds of millions of people,” says Jeffrey Engel, a cold war historian and consultant for the Delta site. The men and women who painted them tried “to use humor in order to cope with the dangers they were dealing with but also bring a little human emotions into a very dark place.”