On the phone one day, the inimical Gere Kavanaugh told me an outrageous story about an article she helped produce several decades ago intended to celebrate the exuberance of design in her beloved home of California. (For many in the field back then, California was, at best, a blind spot or, at worst, a backwater.) She sent her design approach to the publisher in New York and what came back—what got printed—was, to Kavanaugh’s great dismay, nothing like what she had offered. Her work had been stripped to its modernist bones, shoveled into a grid, and drained of the color, messiness, delights, and sensations that represented everything vibrant and meaningful and delicious—everything her practice, and those of the designers she championed, embodied. The mill of an East Coast-cum-European aesthetic had churned up Kavanaugh’s project and reduced it to a monotone of cool gray refinement. So NOT California. “Bad California design will not be tolerated here” was the message she received.

It was a response so lacking in a vision of the way things might be instead of the way things were done by convention and rote, so antithetical to us here on the western edge of the continent—a place of experimentation and daring, a place whose character origins can be traced to an epic fantasy narrative produced by Spaniard Garci Ordóñez de Montalvo in 1510. According to California historian Kevin Starr, Montalvo’s work contains the first mention of “California” as a place, albeit a mythical one that is home to a race of black Amazonians ruled by Queen Calafia, “the most beautiful of all of them, of blooming years, and in her thoughts desirous of achieving great things, strong of limb and of great courage.” This California was a land of women run by brave and powerful women for women. Now, that’s what I call utopia! And maybe this myth isn’t so far from reality, since it seems to me that more than anywhere else, California is a scene where women seem to thrive and prosper and—within this nonfiction narrative of graphic design—gain global influence in unusual numbers. Something in the water, something in the light, something in the air, something going on here facilitates liberation from tradition, from rules, and from the usual way of doing things.

When I first came to California, in 1990, I was sure I had landed in some kind of promised land. I had just left a wintertime Boston, fresh from postmodernist and feminist studies and with substantial experience as a graphic designer (first for a small magazine, then a corporate studio). In contrast to Beantown, California really seemed ruled and galvanized by griffin-riding Amazons. No kindly old gentleman running the show. No “sweethahts” from the mouths of well-intentioned patriarchs who felt duty- and honor-bound to help damsels they assumed could only be in distress. I was stunned by an environment that, had I not witnessed it myself, would have seemed as improbable as Disney’s Tomorrowland. Call it Nopatriarchyland. Here, gender didn’t carry the same stigmas and assumptions. And this freedom from convention also was going on within graphic design. Rather than following the rules, designers in California seemed to be making them up. For women designers, this meant a double whammy, a perfect storm, a jellyroll of change: once liberated from the conventions of the old misogynist social order, they were able to take the next step to unshackle themselves from the conventions of design.

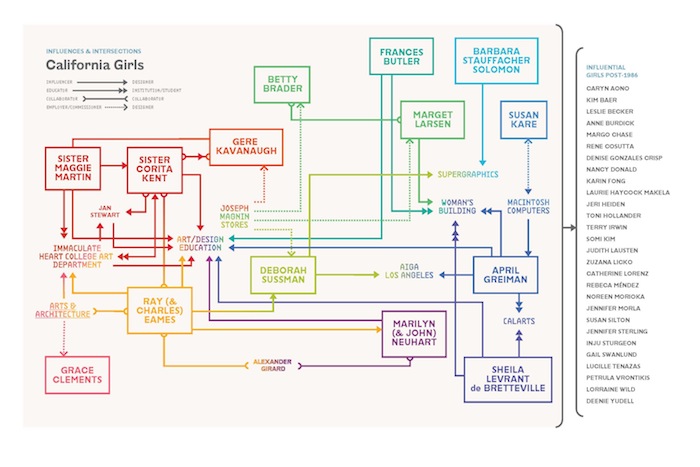

From Grace Clements to Marget Larsen to April Greiman, a continuum of women designers in California defined their identities, their interests, and their professional output for themselves, forging new terrain rather than accepting the usual paths. Clements challenged Surrealism in search of something more real and tangible than dreams and the subconscious. Larsen reenvisioned fashion advertising and marketing as spirited, graphic, solid, and splashy. Greiman exploded onto the international scene by cultivating a new vision for a new tool—the Macintosh.

Yet even in New Amazonia, things weren’t perfect. Like many young women of the 1960s and ’70s, Barbara Stauffacher Solomon and Deborah Sussman strained against sexism and grappled with not being taken seriously. Still, they trailblazed on. With a combination of Manifest Destiny derring-do and a celebratory sense of showwomanship, these maverick designers often flew under the radar only to explode into the sky with bursts of color and joy. Small steps became big strides, and their confidence grew with the momentum. (I can relate!) And the resulting work, as well as the attitude, embodied the California spirit. In a 1966 article in the design trade publication Print, Sister Corita Kent reflected that her students’ projects were “different from most people’s concept of art” and, in comparison with the smooth, technical style of the staid East Coast, they reflected the “rugged Western atmosphere of free expression.”

In the end, the stories of these pioneers provided inspiration around the world, not only to other women but also to other designers, of both sexes. A whole generation of women who burst on the design scene starting in the 1980s thrived in and continued to cultivate the paradise created by their foremothers, mentoring the generations to follow. Think Anne Burdick, Margo Chase, Denise Gonzales Crisp, Laurie Haycock Makela, Jeri Heiden, Terry Irwin, Rebeca Mendez, Noreen Morioka, Jennifer Morla, Lucille Tenazas, and Lorraine Wild, to name just a few.