“Commercial art is a business. It is bought mostly for business purposes, and its cost is entered as a business expense on any company’s books. Because artwork is a competitive product that serves a business function, it should be promoted and sold in the most businesslike manner possible. But it is also something much more.” So wrote Fred Charles Rodewald (1905 – 1955) in 1954 for his book Commercial Art as a Business.

It is more than likely most of you never heard of Rodewald. Yet he served as a very important role model. Rodewald was primarily an illustrator, which included the art of lettering. He took it seriously. In fact, he advocated for commercial artists’ rights to be professional — a pioneer in fair labor practices, you might say — and a leader of the Artists Guild of New York. In 1954 he wrote and illustrated Commercial Art as a Business (Viking Press), a guide to the practical concerns of earning a living as a commercial artist.

He covered pricing, financing, bookkeeping, law, and sales. In his introduction Rodewald cited the census data that there were approximately 80,000 artists in the United States, nearly 20,000 in and near New York, 7,000 in Chicago, 6,000 in Los Angeles, with the total in other cities rarely exceeding 2,500. However, in his day, there were no well-paying salaried art jobs, yet with thousands of newspapers and magazines, illustrated ads, posters, billboards, booklets, folders, and the like, there was freelance gold in them-there-hills. “Our bookstores, libraries, classrooms, and homes contain millions of books and pamphlets filled with pictorial matter of every description,” he wrote. “The clothes we wear, the houses we live in, the countless gadgets we use — all bear the marks of artistic effort.”

“Commercial art, regardless of its ultimate use,” he continued, “remains basically an art — not in any precious or esoteric sense, but because fundamentally it meets with the specifications that apply to all art.” No, commercial art may not “pack an artistic wallop” like the Sistine Chapel murals, but they do have something in common: both were done on commission for a client (and the client was god).

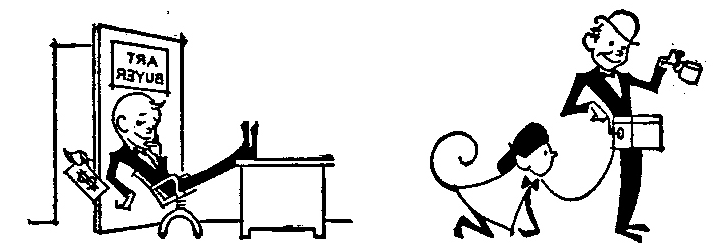

Back in Rodewald’s day, commercial artists who received salaries of $10,000 were usually in some executive capacity, art directors, art managers, art buyers — not producers of art. The salaried job was just a stepping stone to better things. How many successful commercial artists started as job-holders? Well, I couldn’t tell you. But many sat behind desks, made Solomonic decisions between one illustrator and another, until they realized they could do it just as good or better, and get the dough.

Rodewald spent most of his career doing rather than managing commercial art, so he decided that it was important to share his knowledge with up-and-comers. He wrote eloquently about existential things like time, ethics, and even why artwork should be signed. He also shared insight on short cuts, selling, pricing, and what to expect from art directors. But the most revealing chapter is “Kickbacks and Favoritism,” a fact of professional life back then that is little discussed in 2018 (is it?).

It is easy to think that whatever our field is called today, it has not changed much since Rodewald published in 1954. But the excerpt below is unusual (isn’t it?).

There are doubtless art directors and other buyers who extort rebates in return for giving out work. Such kickbacks may range all the way from a fixed percentage of every billing to occasional gratuities in the form of cash, or Christmas and birthday presents of great enough value to place them outside the category of harmless amenities.

Such practices are nothing short of bribery and racketeering, and are not only harmful and costly to the artists, but also to the employers of the guilty individuals. . . In most states they also constitute a crime.

Section 439 of the New York Penal Code defines as a misdemeanor and describes with fair accuracy the type of kickback familiar in the art business, and provides penalties of up to $500 and one year in jail for both parties to the deal. . .

Because evil casts its ugly shadow indiscriminately over all, it should be the concern of all . . . It is therefore a matter of elementary prudence for all art buyers to maintain a reasonable appearance of impartiality as well as to practice it. An art director who plays favorites, and who sometimes goes as far to indicate that he will buy the work of an artist only if handled through a certain studio or representative, must not be surprised if it is rumored that he is receiving kickbacks, regardless of how unfounded such accusations may be. . .

Aside from painstaking correctness in all his dealings involving artists, a good art buyer sees to it, if only in the strictest self-interest, that the artwork he buys is handled fairly and honestly all down the line.