The United States of America more than once employed a media savvy expert who administered, strategized, developed a brand story, and ensured that U.S. assets were optimized. Today that would be called a creative director. In 1917, when America tossed its helmet into the ring of World War I, President Woodrow Wilson, who campaigned on the broken promise not to engage in foreign entanglements, established a wartime information/propaganda office. The Committee on Public Information (CPI) was the first brand consultancy of its kind on a national level for a very specific product — selling and financing the world war. Its “team leader” was George Creel (1876-1953).

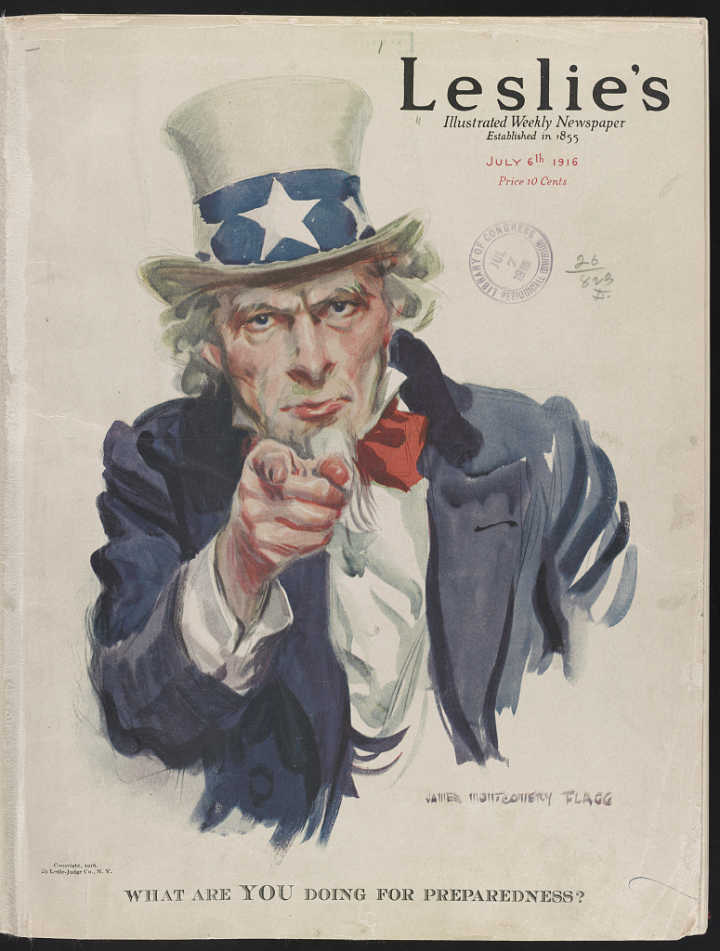

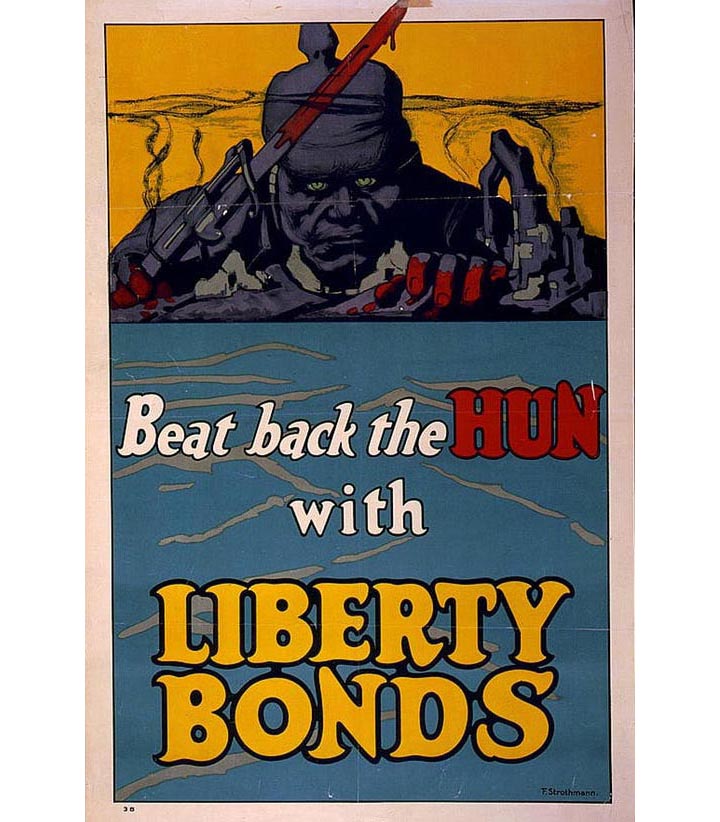

The CPI was used to write, design and otherwise communicate government news to the American people, to sustain morale among citizens, administer voluntary press censorship, and develop propaganda abroad for allies and enemy alike. The creative genius behind the curtain, Creel, was a former newspaper reporter, editor, and publisher. He created 37 distinct divisions, most significantly the Division of Pictorial Publicity, headed by Charles Dana Gibson (famous for his stylish “Gibson Girl” depictions in Life, the humor magazine), staffed by hundreds of the nation's most talented artists who created over 1000 graphic works, paintings, murals, posters, cartoons, and displays that introduced patriotism, fear, and support for war, despite overwhelming popular outcry to remain neutral. Luminary illustrators included Joseph Pennell, N.C. Wyeth, and James Montgomery Flagg (1877–1960).

These were modern times and just as the battlefield was replete with unprecedented weapons, in the opinion of those who were pioneers of propaganda, a new creativity based on overt and covert public mind control was also necessary to fight a bloody war. The foundational message was simple: “When people started to think for themselves the world became a dangerous place. Conformity, loyalty, and fealty to one supreme individual — god or king — made life easier on everyone. The people knew exactly what to do and for whom — reasons were unnecessary.”

Flagg’s most lasting work, the “I Want You! For U.S. Army” poster, doubtless had Creel’s enthusiastic support. It was designed in 1917 but the inspiration came from a 1914 poster by the British illustrator Alfred Leete, which featured Lord Kitchener, the British Secretary of State for War, pointing directly at the viewer and declaring, “Your Country Needs YOU” — the motif was adapted by other warring nations, France, Germany, and Russia, using idealized representations of soldiers in their respective uniforms. Flagg was responsible for reinterpreting the image of Uncle Sam, who he portrayed as vital and authoritative for the cover of the July 16, 1916, issue of Leslie's Weekly, accompanied by the title "What Are You Doing for Preparedness?" The poster is the best known of some 46 works that Flagg created to support the war effort. Flagg himself called his creation "the most famous poster in the world."

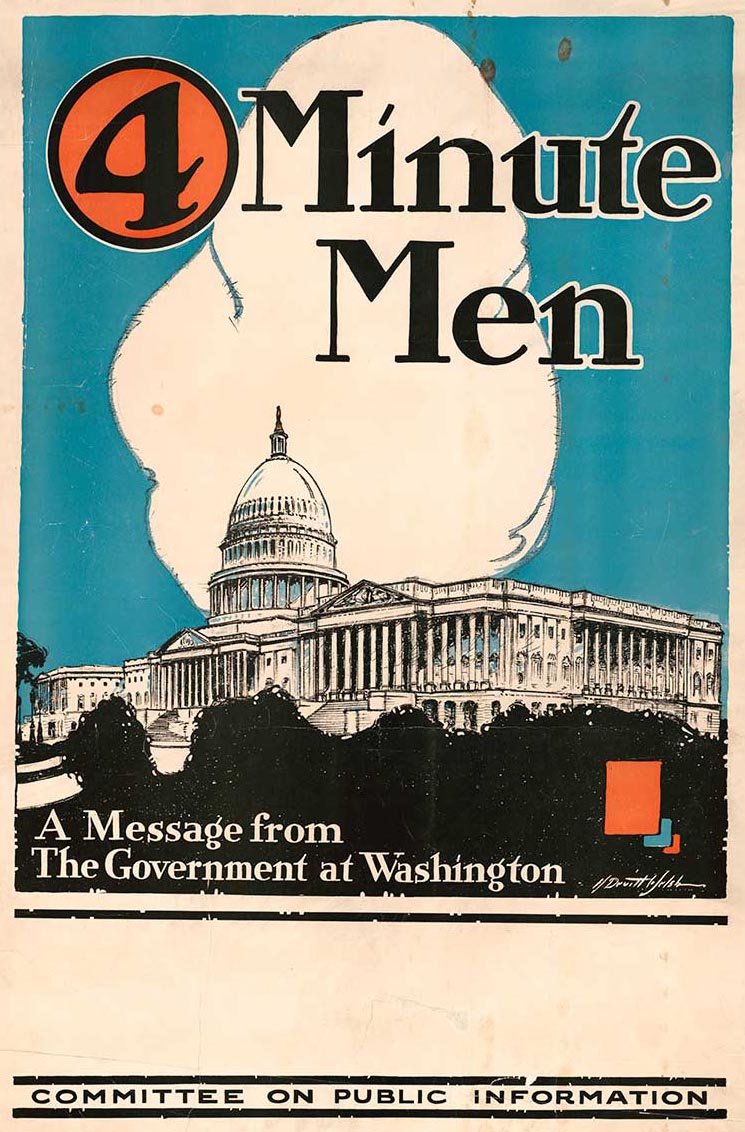

Creel earned his status as America’s creative director through strategic home front events, notably the 4 Minute Men division of 75,000 civilian volunteers who regularly spoke in public to 314 million people over the span of 18 months on efforts like rationing and other victory initiatives. They spoke at social events in movie theaters for a maximum four minutes, which was the typical duration it took to change a movie reel and the time believed to be an average citizen's attention span. Creel micro-orchestrated publicity events down to how speakers should pepper their speeches with dramatic emotional appeals. Between the CPI News Division and Censorship Committee, Creel was able to control the dissemination of official war information.

The CPI was responsible for censorship during the war, which Creel described disingenuously as control of sensitive information: "expression, not repression." Nonetheless, the sedition laws prohibiting antiwar and other demoralizing expression were liberally interpreted and enforced. The CPI ceased on November 11, 1919, upon the signing of the Armistice with Germany. As a model of communications efficiency Creel’s multimedia campaign had set a standard for how branding, as we have come to know it, strategically engaged the modern tools of creative persuasion to underpin a convincing narrative.

“Creel was extraordinarily energetic, quick to make decisions. . . ,” noted David F.Trask, former chief historian of the U.S. Army Center of Military History. “He was capable of inspiring strong devotion” to the cause, massage and client — the United States of America. All are essential qualifications for a creative director, or in this case a propagandist during wartime, in fact, anytime, if such power can be used wisely.