In the 1950s Eliot Noyes was developing the design identities for IBM and Westinghouse, the first holistic approach of its kind for corporations in the United States. At the request of an English design organization, Noyes gave this speech (date unknown), recently found among Paul Rand’s papers by his friend Robert Burns while he was cataloging the final contents of Rand’s home in Weston, Connecticut. Following the passing in December 2017, of the former IBM design buyer and Rand’s wife, Marion Swanee Rand, the house and its contents will being sold for auction. Rand often articulated the importance of visual consistency, it appears that many of his rules were enforced by Noyes. “No design group may make any change or innovation in these disciplines without my concurrence, and that of all other design groups in the company. However, there is still plenty of room for creative effort.” This document sums up Noyes design philosophy that has had incredible impact on generations who practice the art of corporate identity. — Steven Heller

Design Policy for Corporate Buying Design Practice

by Eliot Noyes & Associates Architects and Industrial Designers

Clothes may not make the man, but they do tell something about him.

It is curiously different with corporations. What they really are often has very little relation to how they look. A consistency between corporate character and corporate appearance does not happen automatically and even seems to be a difficult thing to achieve. I am here to suggest that it can be achieved, even in rather large and unwieldy corporations such as IBM and Westinghouse. To make this valid, or even interesting, I should first be showing you visual evidence that an immense improvement in the appearance of IBM has in fact taken place during the six years of the Corporate Design Program, and that Westinghouse in the past year and a half has made a good start. . . .

For the moment . . . I shall have to ask you to assume that IBM, like Cinderella, has indeed been transformed, and that Westinghouse is on the way. I shall talk mostly about IBM, where the program is older, and as a result far more has been accomplished.

I’m sure you know a good deal about IBM and its products, as in fact you must to understand the program. In any case, let me review. IBM is the 26th largest corporation in the United States with a gross annual business of 1.5 billion dollars. Through its subsidiary, the IBM World Trade Corporation, it operates in 89 other countries as well. All told, it has 105,000 employees. In the United States, the company consists of a corporate staff in New York, and eight divisions, each one an almost autonomous operating unit. The corporate staff retains the right to advise and consult with these divisions on many matters, including design, but not to direct them in the handling of their normal business as long as all goes well.

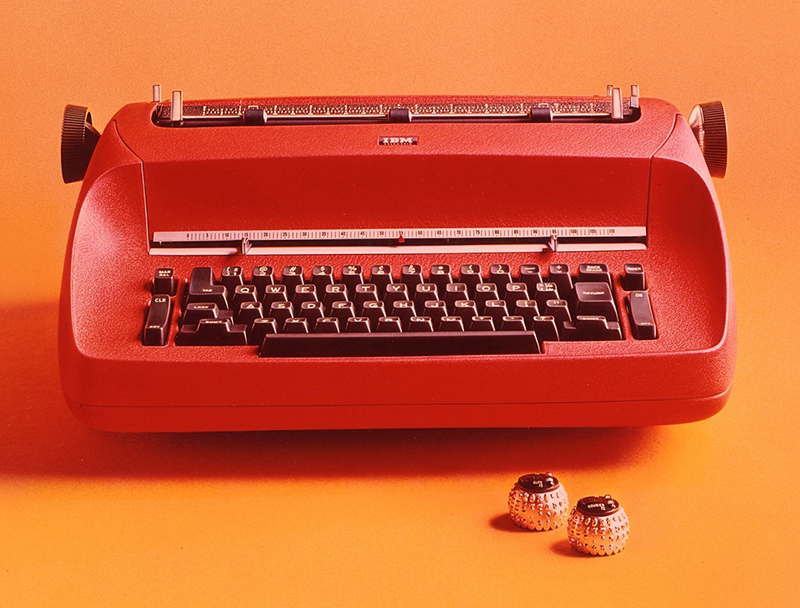

The company products are, of course, business machines of all sorts from typewriters to accounting machines, and up to giant computers, which use advanced electronic techniques to solve speedily the most complicated business and scientific problems. It is in every sense a modern company. The full design program I am conducting began in 1956; but for nine years before I had been retained by IBM to design machines, buildings, interiors, and other such things. Up to this point no large American company had ever embarked on an all-inclusive design program. . . .

When I first met IBM the large main company showroom in New York was a sepulchral space, with oak paneled walls and columns, a deeply coffered painted ceiling, a complex pattern of many types of marble on the floor, oriental rugs on the marble, and various models of black IBM accounting machines sitting uneasily on the oriental rugs. These accounting machines, I might add, often had cast iron cabriole legs in the manner, I believe, of Queen Anne furniture. At the same time in Endicott, New York, a new IBM laboratory building had recently been constructed. It was a Georgian building of several stories with a portico, a pediment, a bell tower, and false wooden beams on the ceilings. Within its air of fraudulent antiquity, sharp modern minds were devising advanced techniques in modern computer technology. Somehow nobody seemed concerned or even very aware of any inconsistency in all this.

During these years I did a good deal of talking about design at IBM and discussed things often with Tom Watson, Jr. (not as yet President of the Company), being quite outspoken about the antediluvian and inconsistent appearance of the company as a whole. Suddenly we began to see the products, the graphics, and the architecture of Olivetti in many publications. Olivetti suddenly became a first-rate example to point to — a company in which a consistent design program was obviously an integral part of its management policies — and obviously paying off handsomely in various senses of the word.

The IBM program was initiated in 1956 at Watson’s personal instigation — he was now president of the company. I explained to him what I needed to make it work.

First, a title: I became Consultant Director of Design.

Second, contact for reporting purposes with the top management of the company. Design must be a function of management, attentive to but not controlled by sales or engineering departments, or any divisional echelons. The program was put under the Director of Communications, a corporate staff office, for coordinating purposes.

Third, an announcement within the company to establish my right to work freely on these problems, and to state partially the goals of the program.

Fourth, an operating budget — not for design but for administering the program.

I am myself an architect and an industrial designer, but not a graphics designer. My first move was to bring Paul Rand into a continuing association with me and the program as Graphics Consultant. In my opinion he is the best graphics designer in our country; he is well known internationally in this field. Graphics design was also logical to start with, because one produces printed material more quickly and more prolifically than products or buildings. The first moves were a redesign of the trademark, the development of certain disciplines for company-wide use in graphics, and the setting up of procedures for Paul Rand both to design many key graphics pieces and to work with internal IBM graphic s groups in the improvement of their work. At one point we made a short film for internal use illustrating these disciplines in the graphics arts program. This has resulted in a tremendous volume of first class graphic design, much of it done by IBM designers working under Rand’s supervision. We are constantly trying to spread the effect of this to the more remote parts of the company.

The most important area is perhaps industrial design — the products themselves. Previous design directions had resulted in a considerable confusion of product appearance ranging from machines with overtones of period furniture to machines resembling large buses with shiny stripes along their sides. With a few exceptions, there was no product design of any quality or suitable character.

In addition, there was in the product design problem an aspect that IBM itself was only dimly aware of — the need for total compatibility of design among the products. During these years, business machine s w ere changing from a few types of accounting machines using punched cards to large electronic data processing systems employing a great variety of machine s in different building block arrangements. It became obvious that any IBM machine manufactured anywhere in the world might find itself if the same installation and same room with products from any other IBM factory. There are in the United States about 6 main laboratory and manufacturing centers - huge plants operated often by different divisions. In addition, there are now five or six new IBM laboratories and factories in Europe developing some products not made anywhere else, but needing to be tied into the IBM family appearance. Each of these laboratories has an IBM industrial design group, consisting of a few designers and some technical people.

My role in this has been first, in the setting of industrial design disciplines which all IBM design groups must follow, and in visiting the tenor so key IBM design groups frequently to guide the course of design, and to make sure of design compatibility. I established the slogan “Everything goes with Everything”. It has taken some persuasion to make it work. A few years ago, one remote design group thought they were pretty far away from New York and decided to develop their own kind of design, colors, and so forth as a matter ‘of local pride. They had to be herded back into the company disciplines. It took a little time, but now everyone follows the rules pretty well. I have insisted on a consistent approach to form, a consistent approach to detailing, and a consistent approach to color.

No design group may make any change or innovation in these disciplines without my concurrence, and that of all other design groups in the company. However, there is still plenty of room for creative effort. For anyone who thinks the disciplines may be too restricting , I often cite the sonnet, as an example. There is no more exacting formula for a poem than those governing the writing of a sonnet in number of lines, meter, and rhyme scheme. Yet much of our finest poetry is written in sonnet form.

Further coordination is maintained by meetings of the design Managers from each laboratory four times a year each time at a different plant or laboratory. This covers most of IBM’s products, and as you see the work is done mostly within the company, under my guidance. In this way close contact is maintained between the company designers and the company engineering groups. Accumulated experience in design as well as technical matters is not lost but built upon. These are designs for the large computer systems, which are either rented or sold. On the other hand, the ET division produces typewriters and dictating machines. These are consumer products, and require a different and a special design handling. The current group has been designed by my office, but IBM at the moment uses no other outside designers of products. The third important design area is architecture. If it takes a thief to catch a thief, perhaps it takes an architect to pick an architect. In any case, business staffs usually have little knowledge or experience which will enable them to select architects that can produce appropriate buildings within such a program. There is no shortage of architectural firm s eager to participate, but there are numerous pitfalls in the process of selecting one for a specific job. An insider in the world of architecture can usually provide either special knowledge or insight that, from the design point of view in particular, is helpful to a corporation in making the right choice. In relation to some fairly specific design goals which are implicit in the Corporate Design Program, I can also usually explain why I want IBM’s Building Construction Department to use architects who will stand up for the art of architecture, while respecting the sanctity of budgets and schedules. I have also succeeded in introducing such internationally well-known architects as Eero Saarinen and Marcel Breuer to IBM, and they have been given key buildings to design, with spectacularly successful results. For many smaller projects in various regions of our country, I have also generally been able to steer the company to competent firms which IBM might not have found by themselves. Within this pattern I have also designed a number of buildings myself. IBM’s architectural program is now well identified for its progressive direction and the company has received special awards from the AlA and continuing good notice in the press for its success in this field. All this brings a gleam of joy to the corporate eye, and, really more important, provides much more attractive buildings and pleasant surroundings for IBM employees.

There are many other areas in which I have been able to exercise some control: interiors of offices, lobbies, and showrooms; the furniture and colors; advertisements; trade shows; window displays; signs; films, and more have all reacted to the program. Other designers of special talent such as Charles Eames, who became a consultant to the program right from the start, have contributed enormously in many ways. Eames, in particular, has found through film s and exhibitions a variety of exciting ways to express the company character and goals.

The results of the total program are many, all rewarding. First, I think IBM has been identified as having pioneered this kind of program on such a scale, and of having done it as well or better than any other company. It has become a classic example, and has been written about endlessly in magazines of all sorts, including Fortune, which recently gave it a long treatment in full color. But IBM knows well that this is not just something arty — to state the case as management sees it, Mr. Watson said recently . . .

“Good design can be a silent partner working for us twenty-four hours a day. As a profit organization, we know that good design is good business and is essential to achieving maximum market advantage.”

Within the company there is a very evident pride in the way the company looks, its new buildings, products, and everything else.

Good design as a way of life has pretty well infused the company thinking. It doesn’t go on automatically though, — it has to be nurtured constantly, and new situations that come up must be coped with almost daily. But that is all part of my normal consulting activity for IBM.

Mostly I have discussed procedures, and you have had to take on faith their alleged success. For this success, I think a special point of view must constantly be at work on the day to day design problems - this point of view must be one which sees corporations not simply as business enterprises but in larger contexts of our economy and our society. In this way, IBM must be understood as a company who se conscious ultimate goal is to help man solve problems that will extend his control over his environment. Similarly, Westinghouse must be understood as a company which is not only involved in our daily comforts and conveniences, but also as a company probing the outer edges of scientific knowledge for our future security and perhaps the survival of the planet. Design programs for these companies must be based to some extent on these concepts and must try to reflect and interpret them through design.

Finally, there must, I think, be single-minded guidance of a design program, unwaveringly supported by the top management of the company. This guidance, in turn, must be exercised by someone scornful of superficial results and firm in the conscientious pursuit of excellence, which in this program is perhaps the combination of practicality and quality. In a sense, excellence should be the true goal of all such programs, if they are to be meaningful. In this context, I would like to read you same thing which appeals to me. It is by John Gardner, President of a foundation, The Carnegie Corporation, in New York…

“We must learn to honor excellence (indeed to demand it) in every socially accepted human activity…

“The society which scorns excellence in plumbing because plumbing is a humble activity and tolerates shoddiness in philosophy because it is an exalted activity, will have neither good plumbing nor good philosophy. Neither its pipe s nor its theories will hold water.”