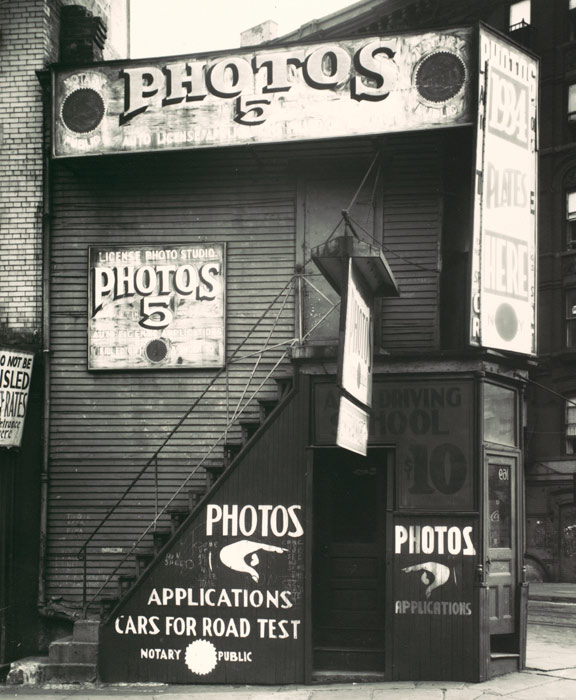

License Photo Studio, New York by Walker Evans, 1934

The final entry in my series of weekly Exposure columns is Walker Evans’ classic photograph from 1934 of a license photo studio in New York. It’s easy to imagine the photographer’s delight in the scene, a chance to shoot a picture about making pictures in which the word “photos” appears six times—it can just about be glimpsed on the suspended sign above the entrance. Evans (1903-75) studied the details of the studio’s haphazard construction with his customary cool but fascinated eye, and made a meticulous visual record, using a large-format, 6 x 8-inch camera.

Offering license applications, license plates, and a driving school, as well as photos for identification, the notary public’s business appears to be thriving despite the fading sign boards and rickety air. The carton-like structure on the street corner is jammed against the brick wall of its neighbor, suggesting an opportunistic later addition, and the outdoor staircase is presumably the only way of reaching the room at the top, where the studio was most likely located. Although the picture tends to be cropped in close to the building when reproduced in books, prints in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art reveal a little more of the scene, including the adjacent sign, “Do not be misled.” Next to the pointing hand on the left, some joker has scrawled “Come up and see me some time,” Mae West’s immortal quip, not once but twice. Reading this three-dimensional text-object as closely as Evans no doubt intended, we also discover a Coca-Cola logo half-concealed inside, framed by the glass door.

Evans exhibited License Photo Studio in “American Photographs” at the Museum of Modern Art in 1938, as picture 80 (of a hundred) in a short sequence devoted to painted signs that draws attention to the characterful exuberance of vernacular letterforms—the entire series is reconstructed in Walker Evans: The Hungry Eye. In the American Photographs book, he underscored the picture’s significance for him by making it the first. The open doorway insistently promising photos, as though the images might materialize within the dark frame between the fingertips, becomes the portal to a manner of seeing that would be hugely influential. (The next image develops the photographic theme by focusing on a grid of studio portraits.) With the passage of time, Evans’ photograph has accrued larger implications. It has become an emblem for the boundless potential of photography, and the profound mystery of netting and preserving likenesses of things that will some day disappear, through the medium of light. The photo studio, too, must have vanished decades ago, and this may be the only surviving photograph. This curious box of a building almost looks like a piece of photographic apparatus in its own right, a two-story camera in the street.

See all Exposure columns