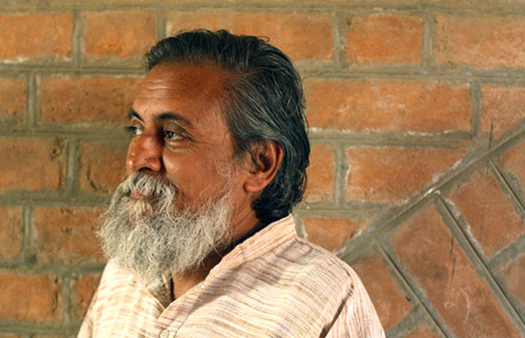

Anil Gupta backed by the signature brick of the Louis Kahn–designed Indian Institute of Management campus in Ahmedabad. Photos: Meena Kadri

A senior faculty member at the Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad, Anil Gupta champions those who are knowledge-rich yet economically poor. His belief that poverty can be alleviated through decentralized, innovation-led enterprises has given rise to several related programs. He formed the Honey Bee Network in the late 1980s to nurture and cross-pollinate grassroots knowledge, creativity and innovation. In 1993, he founded the Society for Research and Initiatives for Sustainable Technologies and Institutions (SRISTI) to provide organizational support to the Honey Bee Network. And in 1997, he created the Grassroots Innovation Augmentation Network (GIAN) to catalyze knowledge into feasible products and sustainable enterprises. Gupta’s semi-annual Shodh Yatra (Journey of Discovery) involves a trek of rural Indian villages to uncover innovative thinking. And the National Innovation Foundation (NIF) he co-established in 2000 provides an assessment procedure and database of grassroots technological innovations. NIF recently gained wide attention by supplying from its archives several inventions featured in the Bollywood blockbuster 3 Idiots, including a scooter-powered flour mill and cycle-driven washing machine.

Anil Gupta spoke with Meena Kadri in Ahmedabad, India, on January 20, 2010.

Meena Kadri

How would you describe your mission across your many initiatives?

Anil Gupta

To enhance the inherent creativity of grassroots innovators, inventors and eco-preneurs while exploring a new paradigm for poverty alleviation that celebrates inclusive development. We focus on devising a knowledge network from village to government level while overcoming the constraints posed by language, literacy and locality. We also facilitate the documentation and cross-pollination of traditional knowledge across India.

Kadri

How do you see these endeavors playing a role in reducing poverty?

Gupta

Most models of development are centered on what the poor don’t have rather than what they have. Some position the poor at the bottom of the economic pyramid, but this does not equate to a lack of knowledge, values and social networks. I prefer to see the poor as a provider than a market — with their limited material resources driving knowledge-intensive, informal innovation. Through providing incubation and development support, patent and intellectual-property-rights assistance, marketing advice and microventure funding, we seek to support the creativity that already exists at the grassroots.

One example of upward mobility is Dharamveer Kamboj, who went from being a rickshaw puller in Delhi’s Old City to an acclaimed organic farmer and innovator in food-processing technology for which he now receives international orders.

Kadri

How are innovations sourced?

Gupta

We have a number of channels, including scouts who tour rural villages, our multilingual Honey Bee newsletter and Shodh Yatra, which focuses intensively on a specific rural region twice a year. Additionally, we support local networks of farmers who discuss experimentation based on local challenges. We also attend an array of fairs, exhibitions and weekly markets, where we both seek and celebrate innovators.

Entrepreneurs such as Mansukhbhai Prajapati, with his range of clay pans, pressure cookers and non-electric refrigerator, do well at such events. His Mitti Cool brand attracts other would-be innovators as a shining example of a successful enterprise that combines technology with traditional knowledge to deliver sustainable solutions.

Once we have sourced innovations and traditional knowledge, we document and decide if they are suitable for cross-pollination and open-source development or whether they require testing, validation, incubation, production and marketing.

Mitti Cool cookware and refrigerator by Mansukhbhai Prajapati, from Gujarat

Kadri

Can you give some examples of the cross-pollination of ideas you foster?

Gupta

Last year we visited farmers in Maharastra who were facing failed cotton crops which were driving increasing numbers to suicide. Much of their discussion revolved around failed pesticides. We had previously gathered knowledge via the Honey Bee Network from cotton farmers elsewhere in India who had found planting bindhi [okra] attracted pests away from the cotton. Elsewhere, jaggery [unrefined sugar] is sprayed on cotton to attract ants, which eat the larvae of pests. These solutions are sustainable as well as productivity-enhancing and were duly passed on to the Maharastran farmers. We also publish our widely distributed newsletter in seven languages to heighten the spread of knowledge, plus we transmit specifically relevant ideas via our local networks and during the Shodh Yatra.

We are currently exploring an internet telephony solution via which we could pair callers’ locations and area of work with knowledge that exists in our database. For example, a farmer from Bihar could receive information on combating pests and weather conditions in his area that have achieved success elsewhere.

Kadri

Many of the innovations I’ve seen have been put forward by men — but I’m sure there must be many by women also.

Gupta

Indeed! The pedal-powered washing machine featured in the film 3 Idiots was inspired by the invention of 20-year-old Remya Jose from Kerala, which has been showcased on the Discovery Channel.

We sourced a drink made from the Opuntia [prickly pear] cactus fruit from women in Saurasthra that sold exceptionally well at our annual Stavik Food Festival. The festival attempts to enhance demand for local crops to stimulate market-based incentives for their conservation and cultivation. We provided festival goers with nutritional information for the drink based on testing at our SRISTI lab. We’re now in discussions with the Indian railways to see if we can sell the drink on board their trains, which serve 18 million passengers daily.

There are countless women innovating but a memorable success story was Valsamma Thomas. We helped to develop her herbal hair-oil using local ingredients. She did so well off the venture that we later received a photograph from her proudly displaying the new car she had purchased with her profits.

Kadri

Could you expand on the sustainable nature of many of the grassroots initiatives?

Gupta

When you combine a scarcity of resources with an abundance of knowledge, sustainable solutions are a common result. Those at the grassroots inherently look for ways to co-opt nature and conserve energy. Our Shodh Yatra explorations demonstrate that rural innovations tend toward sustainable solutions with frugality, durability and multi-functionality being part of the mix. Re-purposed technology, such as bicycles, feature often in transformed roles to meet a variety of needs. From agricultural innovations to the gas-powered iron or pressure-cooker-driven coffee maker, we find that solutions developed by producers who are also users reflect the concerns of both the production and consumption environments.

Gas-powered iron by K Linga Brahman, from Andra Pradesh

Pressure-cooker coffee maker by Mohammed Rozadeen, from Bihar

Kadri

What are some of the biggest challenges you currently face in your work?

Gupta

We source many genuine innovations that address local problems, but some do not become products due to lack of fine-tuned design. We’d like to explore a model whereby professional designers give their time as a form of investment in the eventual product. Grassroots innovators can devise needs-based solutions in an anticipatory manner but need assistance to test, scale, market and distribute — we can manage some of this but would like to utilize professional institutes, perhaps on a deferred-payment basis.

And of course one of the biggest challenges that’s driven me for some time now is — when things turn out well — ensuring that the honey gets spread around!

Kadri

While we’ve been sitting here you’ve had a number of students visit your office for various requests, plus taken many phone calls, and at one stage you were juggling two handsets and their respective callers to co-ordinate an event. Does it ever seem like just too much for one person?

Gupta

Well, of course it’s not just me — we have a great team across our various organizations and local networks, plus many volunteers and students who bring their energy and commitment. I feel that through this kind of collaboration and facilitation we can turn vicious circles into virtuous ones. Really, there is so much to do because there is such a wealth of innovation to be tapped and channeled. And of course the real work — and indeed the success — happens not in an academic office but at the grassroots itself.