LEFT: Minganji Masqueraders, near Gungu, Congo (Democratic Republic), 1970, Eliot Elisofon / National Museum of African Art. RIGHT: Wall Hanging, 1926, Anni Albers / Harvard Art Museums / Busch-Reisinger Museum, Association Fund © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation

African collections are simply massive.

Did you know there are over 200,000 African objects at the British Museum; 20,000 at the Belgium Royal Museum; 70,000 at the Musée du Quai Branly; and over 26,000 at the Met? And the list goes on. So what do these numbers represent? Art, artifacts, colonialism, capitalism, shame? Yes. But there’s something else present in the data. Something powerful. Think of it: because of the volume, because of the dispersement, because of the accessibility, we’re witnessing perhaps the most influential art in the world — namely African art.

Now ask yourself, for such a massive art movement, quite literally, have you ever studied its impact at length, in school? If not, why? Well all that is about to change.

The painful history of the African diaspora includes not only the displacement of human life but also its cultural artifacts. It is estimated that “90 to 95 percent of Africa’s cultural heritage is held outside Africa by major museums.” That fact is jarring. And new. A report commissioned by President Emmanuel Macron in 2018, evaluated these collections and recommended that French museums “return artworks that were removed from Africa without consent if their countries of origin ask for them back.” Now that’s a proclamation with promise. And may indicate that finally, the arc of the moral universe is bending towards Africa. But only time will tell.

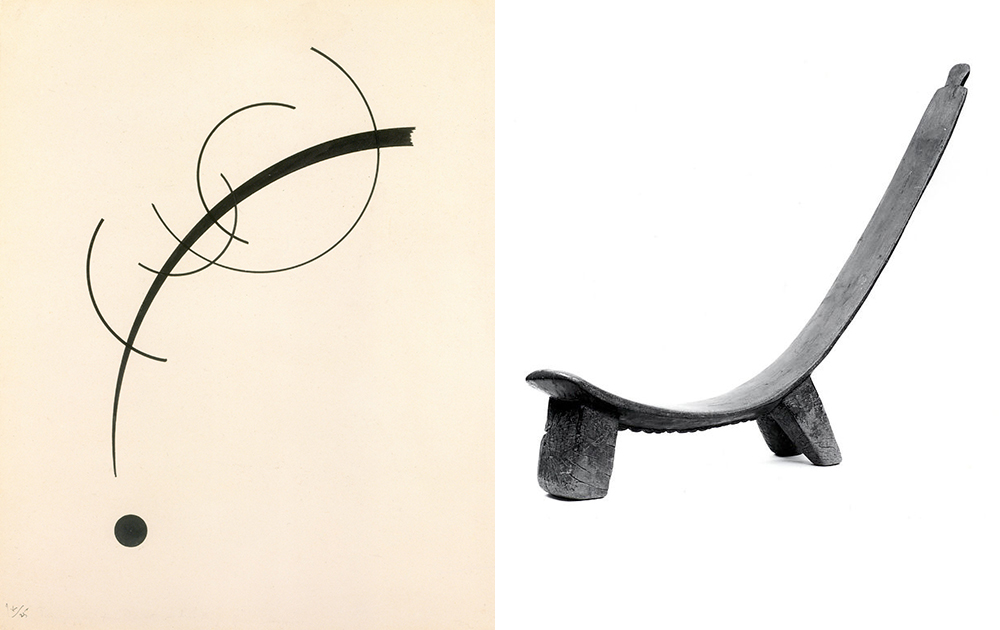

LEFT: Free Curve to the Point — Accompanying Sound of Geometric Curves, 1925, Vasily Kandinsky / Metropolitan Museum of Art Rogers Fund, 1970. RIGHT: Chair (Dâgalo), Burkina Faso, Black Volta River region, 19th–20th century, Nuna / Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Gift of Mrs. Gertrud A. Mellon, 1971

In the meantime, as we wait for repatriation, this art-without-borders continues to have global impact. “Two thousand years of history could not be wiped away so easily” is heard from every shelf, on every display, in every exhibit. One such history — that of modernism — is under reinvestigation. “In order to understand the full spectrum of the aesthetic foundations for early modernism” writes Denise Murrell, the amazing new curator for 19th and 20th century art at the Met, “an investigation of African influences in modern art remains relevant today.”

How surprising. For something that began over 100 years ago, why does it remain relevant today? Well, it seems that history has selective memory — and those who do the selecting, determine how it’s being remembered. So to broaden the scope, to make history more inclusive, maybe we need a new method of selection. Why yes! And that new way is here. Well almost. It’s only 10 paragraphs away. Do read on!

LEFT: Screen (Insika), Rwanda or Burundi, early to mid-20th century, Tutsi peoples / Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, William B. Goldstein and Marie Sussek Gifts, 2010. RIGHT: “MR” Armchair, 1927, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe / Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Theodore R. Gamble Jr. Gift, in honor of his mother, Mrs. Theodore Robert Gamble, 1980

Indeed “art historians play a significant role in shaping our understanding of the past.” So watch anything you can by historian Gus Casely-Hayford. And through his eyes, your world will change, in the same way that the art world changed at the beginning of the 20th century — “something was about to happen and you could feel it in the air.” African art had been “imported into Paris for a long period of time but the turn of the 20th century was when it really caught fire.”

Cue up Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. What do you know of this painting? That it appropriated African motifs? That it changed the course of art history? That these two things were related? (Well, two out of three ain’t bad.)

We’ve learned that Picasso's radical approach to art-making was achieved through a new aesthetic style and departure from naturalism, both of which were inspired by Africa. But does that acknowledgement go far enough? Consider this instead: Les Demoiselles was not a painting but a thought process — an African thought process — a new philosophy adopted by Picasso, Matisse, and others, that completely altered the course of western history. This reframing is revealing. It ascertains that this art, this African art “actually gives birth to the idea of modernity.”

So African ingenuity helped shaped the modern movement, which shaped the 20th century — profoundly. It was a catalyst for change. A new direction. A shift in thinking. A shift in my thinking. Now I can’t help but see the influence — from prehistoric cave art, to Egyptian motifs, to sub-Saharan sculpture, to “instinctive” geometric textiles, to symbolic language systems, to body art, to the craft of weaponry — our visual world today is awash with the visual influences of Africa. Murrell also adds that "in the contemporary postcolonial era, the influence of traditional African aesthetics and processes is so profoundly embedded in artistic practice that it is only rarely evoked as such.”

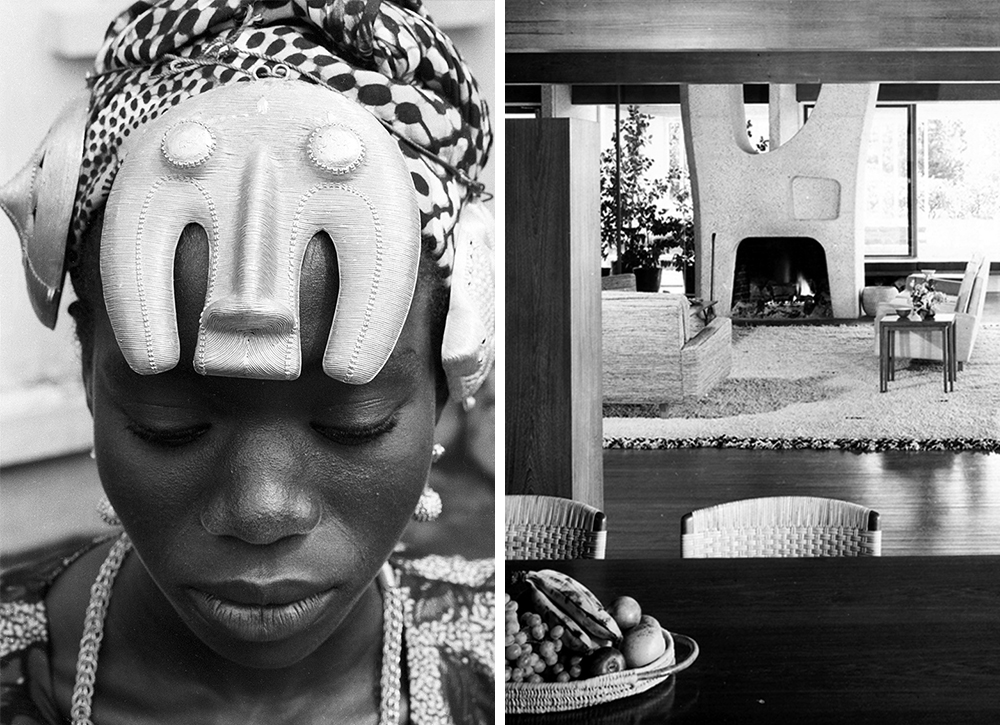

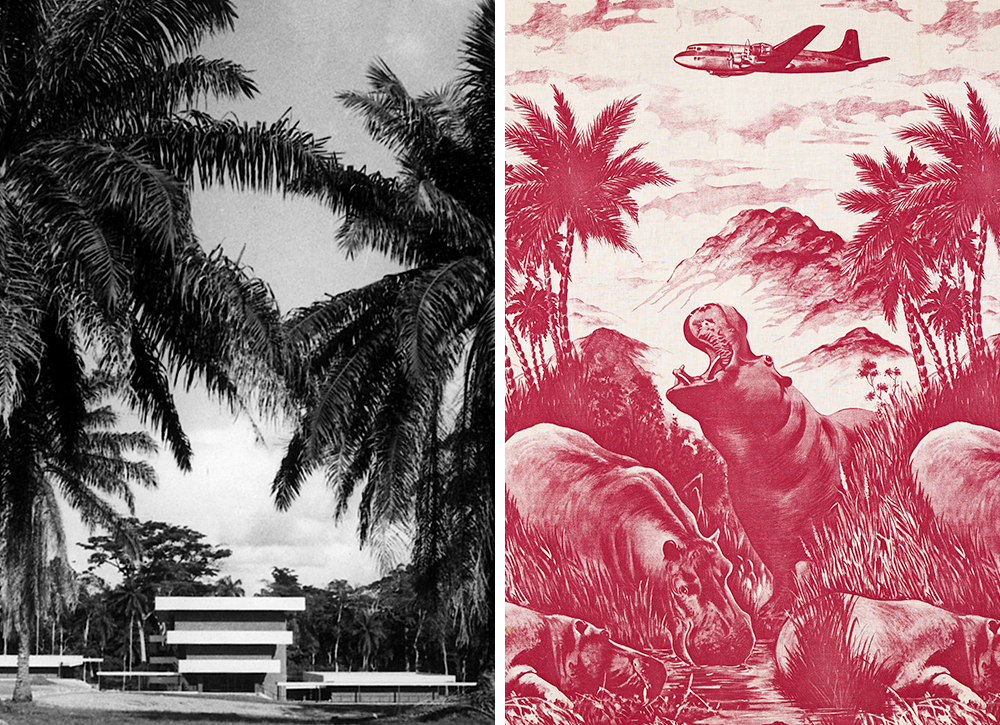

LEFT: Franc̦oise Dao Alouette, Anna village, Ivory Coast, 1972, Eliot Elisofon / National Museum of African Art. RIGHT: Gagarin House I (detail), designed by Marcel Breuer, interior view, 1954, Ben Schnall / Marcel Breuer papers, 1920–1986 Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

And here’s where it gets interesting: we can trace African innovation through modern art, but how about through modern design?

The Bauhaus turned 100 this past year. Our fascination with this school culminated with a celebration of squares, circles, and triangles (fondly known as Albers, Brandt, and Itten). Such geometry speaks to me. As the daughter of a mathematician, from a family who celebrated Pi Day as a national holiday, we paid homage to the square. But can simple geometry encapsulate the Bauhaus ethos? I wonder. Take a look at the designs from a 1938 Bauhaus exhibit at the MoMA. There, believe it or not, you’ll see complexity, diversity and decoration. It’s not all “clean lines and pure materials.” The point is this: modernism is diverse. And history is edited.

“Given its diasporic influence in our lives today, the Bauhaus is so familiar that we think of it as a form of ur- modernism, a point of mythic origin.” Mythic origin? Really? Just look into the eyes of an Oskar Schlemmer mask, however, and you’ll see someone familiar: It was precisely at this time that King Tut’s tomb was discovered, which prompted heightened interest in Ancient Egypt across Europe and across art disciplines. So the influence is there but sometimes the acknowledgment is not. To start the discussion at the Bauhaus, therefore, is like beginning the alphabet on the second letter, which limits our understanding of history.

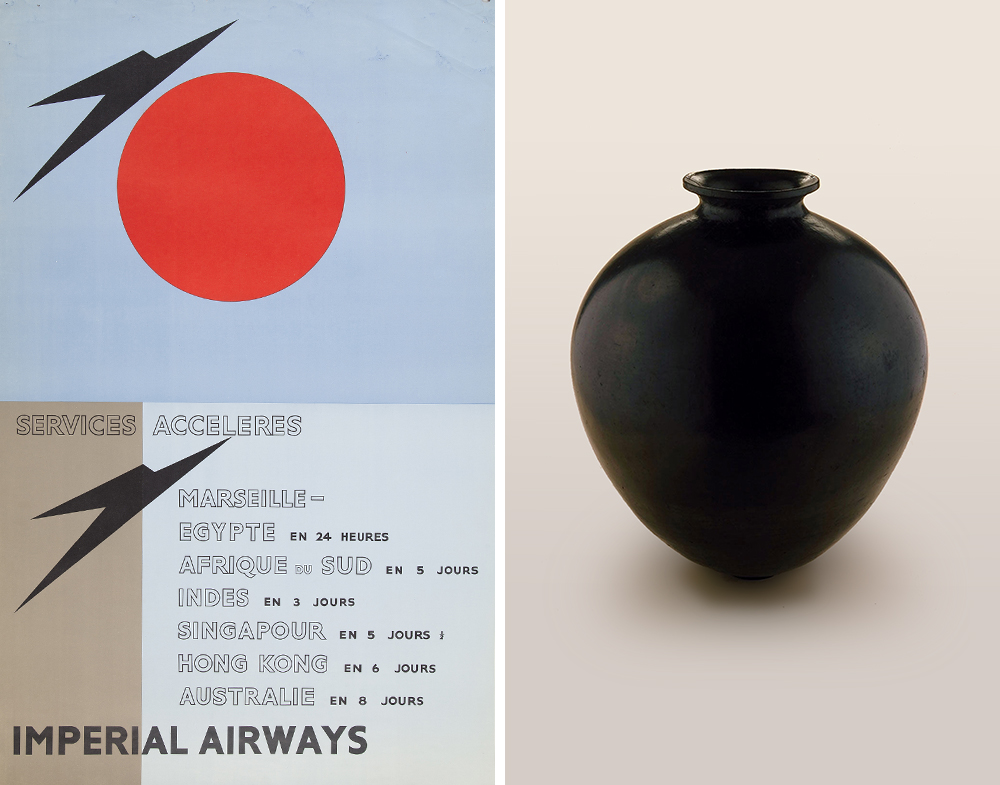

LEFT: Imperial Airways Services Acceleres Poster (detail), UK, 1938, Ben Nicholson / National Air and Space Museum. RIGHT: Jar, Western Inter-Lacustrine region, Uganda, mid-20th century, Nyoro artist / National Museum of African Art

As a matter of fact “artists in Germany between the world wars worked extensively with African compositional devices as they rejected naturalism as inadequate to their project of representing the anxiety, dislocation, and utopian fantasies of interwar German society.” These motifs can clearly be seen through the work of Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinksy, masters at the Bauhaus program. They can then be traced through their colleagues and students too.

Let’s start with the obvious: I see African motifs in Marcel Breuer and Gunta Stölzl African Chair of 1921. I see ancient x-chair construction in Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Chair of 1929. I see the lineage of African and South American geometry in Anni Albers weavings of 1936. I see African metalwork in the floor graphics of a Herbert Bayer exhibit plan of 1938. I see prehistoric wall motifs in Marcel Breuer architecture from 1957.

I see all these images, right now, through the vast digital collections at the Smithsonian Institution (and peer museums). As part of a fellowship through the Smithsonian Center for Learning and Digital Access (SCLDA), I’m curating an image collection on their Learning Lab platform — a powerful tool that can access “millions of images, recordings, and texts” across all SI museums. This project is meant to help teach more inclusive design histories in higher education. But watch out — the tool is addictive. Africa. Modernism. Geometry. Congo. Seated Figurine. Homage to the Square. Keïta. Gunta. Red. 1919. What will these keyword searches produce? My heart’s aflutter with anticipation. Then suddenly over 1,000 results appear. Form follows [algorithmic] function. And from these results, a collection is made. Then shared. And finally, the moment we’ve been waiting for — a new method of selection! A new way of knowing! A citizen history!

Gone is the history textbook. Gone is the single author. Gone is the set narrative. In its place are teachable images, networked collections, and metadata. Again, something is about to happen and you can feel it in the air. It’s called Open Access and will dramatically impact how we teach and learn. Just this year, the Smithsonian made close to 3 million images “open” or “open for use without any restrictions” following initiatives by the Met and the British Museum. To do what, you ask? Well, to 3D print a model of Rosetta Stone when teaching symbol systems, of course. Or to learn typography by printing your own facsimile of an Ethiopian Illuminated Gospel. Or to adopt an African thought process into your next painting which may one day radically and recognizably alter history.

LEFT: Faculty of Humanities Buildings (detail), OAU Campus, Ile-Ife, Nigeria 1962, Courtesy of the Arieh Sharon Digital Archive ariehsharon.org. RIGHT: Factory Printed Cloth (detail), Sierra Leone, ca. 1959, Undetermined artist / National Museum of African Art Gift of Donald A. Theuer and Lilburne Theuer Senn

Again the collections are massive:

There are 2,335,338 open access images at the British Museum. 406,000 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. And now 2,800,000 at the Smithsonian Institution. While many of these scans offer African objects, by no means is this restitution. Not in the least. However, global access to digital collections may help students find and trace Africa’s profound impact on design, which is an exciting new area of research and pedagogy. Just think of it: because of the volume, because of the dispersement, because of the accessibility, we’re witnessing perhaps the most influential moment in history — namely open history.

Notes:

Special thanks to Darren Milligan, Cody Coltharp and Tracie Spinale (Smithsonian Center for Learning and Digital Access); and Karen Milbourne (National Museum of African Art).

In consideration for the ritualistic practice captured in the Minganji Masqueraders' photo, here is more information from its metadata:

“Although the Minganji face masks make an appearance at a wide variety of occasions (such as the investiture ritual of a local chief, or the construction of a new chief’s residence), their primary role is as guardian of the initiation encampement. The Minganji masks, other than the Gitenga mask, embody death, uncertainty, and darkness." [Petridis C., 1993: Pende Masks styles. Face of the Spirits].”

To use the Smithsonian Learning Lab collection in your classroom, click on the image below: