Cover of Bibliodyssey: Amazing Archival Images from the Internet, based on the weblog by PK; designed, edited and published by Fuel

Are graphic design skills transferable? Does being a graphic designer equip a person to do anything other than be a graphic designer? I know half a dozen designers — friends and associates — who are using their professional know-how to launch alternative or parallel careers. I'm not extrapolating a trend here: but there's something in the harsh ecology of contemporary graphic design that is encouraging certain sorts of designers to use their skills, instincts and sensibilities to create alternative ways of earning a living. One of the most interesting examples of this is the publishing venture set up by the British design group Fuel.

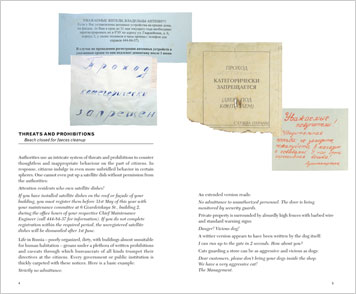

Spread from Bibliodyssey: Amazing Archival Images from the Internet, based on the weblog by PK; designed, edited and published by Fuel

Fuel were the most daring and self-aware of the U.K. design groups to emerge in the post-Brody era. Less fashionable than Tomato or Designers Republic, they had an arty hauteur that made them graphic design outsiders. In the early 1990s it was common to see the three Fuel men staring out of photographs wearing sharply tailored matching pinstripe suits and fuck-you expressions. They eschewed the mateyness of most British graphic designers in favor of a dash of menace backed up an air of calculated detachment. Or to put it another way, they conducted themselves like junior members of the Brit Art movement, a connection that remains active today: on their website they list Tracey Emin, Jurgen Teller and Jake and Dinos Chapman as clients, and their studio is in the same East London street as the home of the dapper Godfathers of Brit Art, Gilbert and George.

Damon Murray, Stephen Sorrell and Peter Miles formed Fuel in 1991 (Miles left in 2004). They produced graphic design for a variety of clients including MTV, Levi's, Diesel and the Sci-Fi Channel, and yet the trio declined to follow the path of growth that so many other design groups chose at that time. Instead they put their energy into producing self-initiated books and films. The most ambitious of these projects was Fuel 3000, a hefty tome that acted as a manifesto for their brutalist, non-ingratiating style. The book was an emotionally glacial mix of images and text that navigated a course through the 21st century media world of instant gratification and glassy-eyed fixation with the surface of things. In twenty years time, Fuel 3000 will be seen as far more emblematic of its era than most of the boosterish eye-candy design books published at the same time.

Fuel's interest in personal authorship had started at the Royal College of Art where their eponymous magazine, with its quixotic use of vernacular motifs and crude default typography, seemed like a rebuke to the seductive design of their style-besotted contemporaries. Yet when Rick Poynor wrote about them in 2000, in an essay entitled "Power to Translate" (reproduced in his book Obey the Giant), he commented "... Fuel certainly didn't regard themselves as exponents of 'graphic authorship' — a term they had not heard until the late 1990s, when they reacted to it in conversation with derisive laughter."

My guess is that the derisive laughter was an admission that Fuel knew — even then — that they were not indulging in pure graphic authorship, rather that they saw themselves as editors. As they told the British journal Design Week in a recent interview, "editing text has much in common with art directing in terms of deciding what to take out and what to leave in, and it's all problem solving, whether its for a client or a personal project."

A talent for editorship has led them to become publishers and establishing Fuel Publishing. As they also told Design Week: "Half of the business now is publishing, so the books have to pay for themselves. Obviously each book is a huge undertaking and financial risk, so there's a rigorous process from the initial idea to the possibility of realization before we develop individual titles."

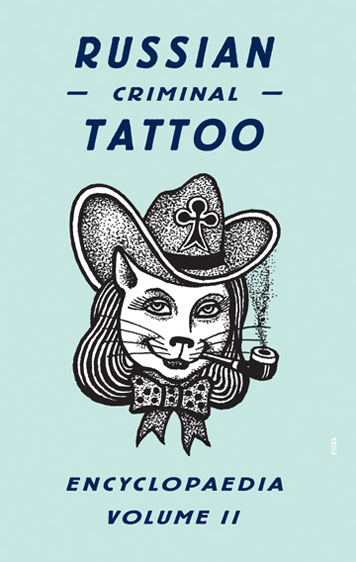

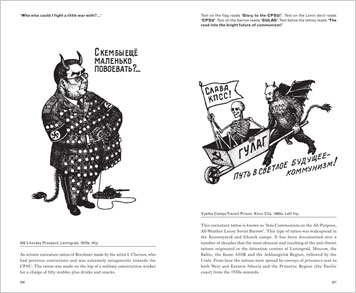

Cover and spread of Russian Criminal Tattoo, Encyclopaedia II, designed, edited and published by Fuel

Looking at Fuel's small, carefully nurtured backlist, it appears that they have entered a new phase. Detached scowling and graphic obliqueness have been replaced by a warmer, less austere sensibility that has allowed them to produce books with surprisingly broad appeal. Fuel's books have a cultural reach that lifts them out of the design ghetto and into the world of book chains and the review pages of broadsheet newspapers. Their two surveys of Russian criminal tattoos have become cult hits; a book on English football match-day programs, from the era before David Beckham and the merging of football and fashion, offers a guide to an ignored strata of British graphic design; and a book pairing Andy Martin and the eccentric "performance poet" and broadcaster Ian McMillan shows what happens when publishers make inspired commissions. Their latest volumes include a return to Russia and a book inspired by an entry they found on Design Observer.

Murray and Sorrell's realization that they possessed the transferable skills and instincts to publish thought-provoking books with editorial depth, has allowed them to create a publishing venture that offers a fresh take on visual culture. It's a venture that their design background — especially their early explorations into graphic authorship — has equipped them well to undertake.

Cover and spread of Notes from Russia by Alexei Plutser-Sarno; designed, edited and published by Fuel