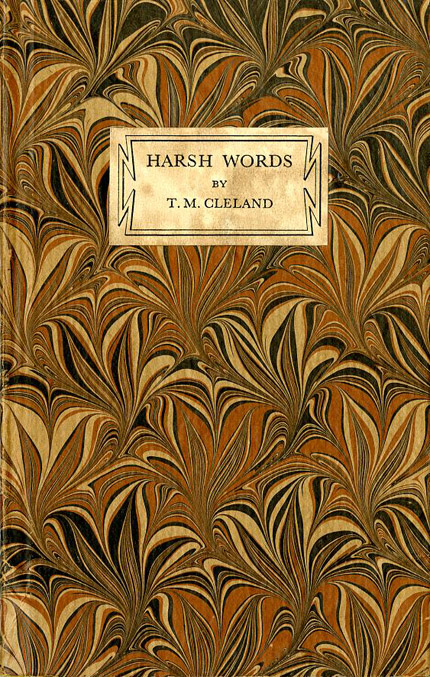

Design criticism may be comparatively new, but critical designers are not. During the late nineteenth century, William Morris was known to scold his fellows over the erosion of design standards brought about by the industrial revolution. Two decades later, William Addison Dwiggins routinely complained about the continuous decline in aesthetic virtuosity. The grousing — I mean, reflective critical debate — continued through the twentieth century. One of the not-so-genteel of the designer critiques was “An address delivered at a meeting of The American Institute of Graphic Arts in New York City” on February 5, 1940, “on the occasion of the opening of the Seventeenth Annual exhibition of the Fifty Books of the Year” by Thomas Maitland (T.M.) Cleland (and later published by the AIGA as a keepsake). Cleland's ominously titled Harsh Words began thus:

“The generosity of your invitation to me to speak on this important occasion leaves me a trifle bewildered. I am so accustomed to being told to keep my opinions to myself that being thus unexpectedly encouraged to express them gives me some cause to wonder if I have, or ever had, any opinions upon the graphic arts worth expressing.”

Whether they were worth expressing was ultimately in the ear of the receiver; nonetheless, Cleland had a lot to say: 39 pages, over 5000 words worth of displeasure with the state of the book and typography and a lot more that he disingenuously hoped “will not be thought an abuse of this kindly tendered privilege.”

The AIGA elders doubtless knew what they were in for. This was a celebration of printing and typography, but Cleland, a book designer who designed the first cover of Fortune Magazine in 1933, had his sights on bigger game than the 50 Best Books. His mission, he declared, was “to deplore the fifty thousand worst books, which may be seen elsewhere.”

“If I can only develop it in terms of a tree…," he said of his aesthetic vision, "the tree I have in mind is cultural civilization: one of its limbs is art, and a branch of this we call the graphic arts; and a twig on this branch is printing and typography.” Among his prime bugaboos is “the idea that originality is essential to the successful practice of the graphic arts, [and] is more prevalent today than it ever was in the days when the graphic arts were practiced at their best.” Responding to the end of the so-called avant-garde era of experimentation, Cleland cautioned, “The current belief that everyone must now be an inventor is too often interpreted to mean that no one need any longer be a workman.”

Sound familiar? Today’s notion that the computer will undo all the genius the hand hath wrought? “The conscious cultivator of his own individuality will go to extravagant lengths to escape the pains imposed by a standard,” he added. Can you hear the cheers, such as the kind punctutating the State of the Union address, following key passages?

Another of Cleland's bêtes noires was “the superabsurdity” of modernism. “Embraced with fanatic enthusiasm by many architects and designers is the current quackery called ‘Functionalism,'” he wrote. Cleland reveled in ornamentation, so it's to be expected that he argued against “a new gospel for the regeneration of our aesthetic world ... [that restricted] all design to the function of its object or materials.” Like many designers of his day who distrusted the motives and outcomes of a younger generation (e.g., Paul Rand, Lester Beall, Bradbury Thompson), he saw modernism as merely the latest among “the new religions and philosophies that have paraded in and out of our social history for countless generations.”

While attacking the coupling of ideology with design (“the simple addition of an ‘ism’,” he sneered), Cleland aimed even more barbs at the popular Streamline style, as practiced by the industrial designers Raymond Loewy, Norman Bel Geddes, Henry Dreyfus and Walter Dorwin Teague). This work he decried as “unsightly” and a reflection of “mass vulgarity.”

Cleland reached his critical crescendo when discoursing on type and printing. He accused the modernists of simplifying traditional forms of type “as you might simplify a man by cutting his hands and feet off." He added, “You can no more dispense with the essential features of the written or printed Roman alphabet, ladies and gentlemen, than you can dispense with the accents and intonations of human speech. This is simplification for simpletons, and these are block letters for blockheads.”

“We hear now of ‘left wing’ artists,” he went on about designers with noncommercial, save-the-world ambitions. “As nearly as I can discover, these are to be recognized by their contempt for any sort of craftsmanship and peculiar ability to keep their drawings clean. They make penury a pious virtue, and they are not infrequently big with pretension to being the only serious interpreters of life and truth.” Even back then, eh? But Cleland reserved bile for the slick professional too, "the school of ‘economic royalists’ who have made of art a commercial opportunity.” That is to say, industrial designers with large staffs, who have “welded art and commerce so successfully that it is nearly impossible to tell them apart.”

What Cleland was looking for was “somewhere between the two…” an artist not quite poor enough to be picturesque, just well enough off “to keep his collar and his drawings clean.”

My point in quoting Cleland’s Harsh Words is not to ridicule him for being reactionary or curmudgeonly. He was a highly respected designer who had the courage to stand before a (substantially unsympathetic) audience and debate issues important at the time. He didn't have the comfort of ducking behind a blogger's pseudonym, which accounts for the humility that took some of the sting out of his rant. “I humbly pray, ladies and gentlemen," he wrote, "that you will apply no instruments of precision to my words — they are the best I could find in this emergency for saying what I believe to be true. If you think me guilty of exaggeration, the foregoing remarks are my only defense. But if you accuse me of being facetious, I will tell you that I have never been more serious in my life.”

“The generosity of your invitation to me to speak on this important occasion leaves me a trifle bewildered. I am so accustomed to being told to keep my opinions to myself that being thus unexpectedly encouraged to express them gives me some cause to wonder if I have, or ever had, any opinions upon the graphic arts worth expressing.”

Whether they were worth expressing was ultimately in the ear of the receiver; nonetheless, Cleland had a lot to say: 39 pages, over 5000 words worth of displeasure with the state of the book and typography and a lot more that he disingenuously hoped “will not be thought an abuse of this kindly tendered privilege.”

The AIGA elders doubtless knew what they were in for. This was a celebration of printing and typography, but Cleland, a book designer who designed the first cover of Fortune Magazine in 1933, had his sights on bigger game than the 50 Best Books. His mission, he declared, was “to deplore the fifty thousand worst books, which may be seen elsewhere.”

“If I can only develop it in terms of a tree…," he said of his aesthetic vision, "the tree I have in mind is cultural civilization: one of its limbs is art, and a branch of this we call the graphic arts; and a twig on this branch is printing and typography.” Among his prime bugaboos is “the idea that originality is essential to the successful practice of the graphic arts, [and] is more prevalent today than it ever was in the days when the graphic arts were practiced at their best.” Responding to the end of the so-called avant-garde era of experimentation, Cleland cautioned, “The current belief that everyone must now be an inventor is too often interpreted to mean that no one need any longer be a workman.”

Sound familiar? Today’s notion that the computer will undo all the genius the hand hath wrought? “The conscious cultivator of his own individuality will go to extravagant lengths to escape the pains imposed by a standard,” he added. Can you hear the cheers, such as the kind punctutating the State of the Union address, following key passages?

Another of Cleland's bêtes noires was “the superabsurdity” of modernism. “Embraced with fanatic enthusiasm by many architects and designers is the current quackery called ‘Functionalism,'” he wrote. Cleland reveled in ornamentation, so it's to be expected that he argued against “a new gospel for the regeneration of our aesthetic world ... [that restricted] all design to the function of its object or materials.” Like many designers of his day who distrusted the motives and outcomes of a younger generation (e.g., Paul Rand, Lester Beall, Bradbury Thompson), he saw modernism as merely the latest among “the new religions and philosophies that have paraded in and out of our social history for countless generations.”

While attacking the coupling of ideology with design (“the simple addition of an ‘ism’,” he sneered), Cleland aimed even more barbs at the popular Streamline style, as practiced by the industrial designers Raymond Loewy, Norman Bel Geddes, Henry Dreyfus and Walter Dorwin Teague). This work he decried as “unsightly” and a reflection of “mass vulgarity.”

Cleland reached his critical crescendo when discoursing on type and printing. He accused the modernists of simplifying traditional forms of type “as you might simplify a man by cutting his hands and feet off." He added, “You can no more dispense with the essential features of the written or printed Roman alphabet, ladies and gentlemen, than you can dispense with the accents and intonations of human speech. This is simplification for simpletons, and these are block letters for blockheads.”

“We hear now of ‘left wing’ artists,” he went on about designers with noncommercial, save-the-world ambitions. “As nearly as I can discover, these are to be recognized by their contempt for any sort of craftsmanship and peculiar ability to keep their drawings clean. They make penury a pious virtue, and they are not infrequently big with pretension to being the only serious interpreters of life and truth.” Even back then, eh? But Cleland reserved bile for the slick professional too, "the school of ‘economic royalists’ who have made of art a commercial opportunity.” That is to say, industrial designers with large staffs, who have “welded art and commerce so successfully that it is nearly impossible to tell them apart.”

What Cleland was looking for was “somewhere between the two…” an artist not quite poor enough to be picturesque, just well enough off “to keep his collar and his drawings clean.”

My point in quoting Cleland’s Harsh Words is not to ridicule him for being reactionary or curmudgeonly. He was a highly respected designer who had the courage to stand before a (substantially unsympathetic) audience and debate issues important at the time. He didn't have the comfort of ducking behind a blogger's pseudonym, which accounts for the humility that took some of the sting out of his rant. “I humbly pray, ladies and gentlemen," he wrote, "that you will apply no instruments of precision to my words — they are the best I could find in this emergency for saying what I believe to be true. If you think me guilty of exaggeration, the foregoing remarks are my only defense. But if you accuse me of being facetious, I will tell you that I have never been more serious in my life.”