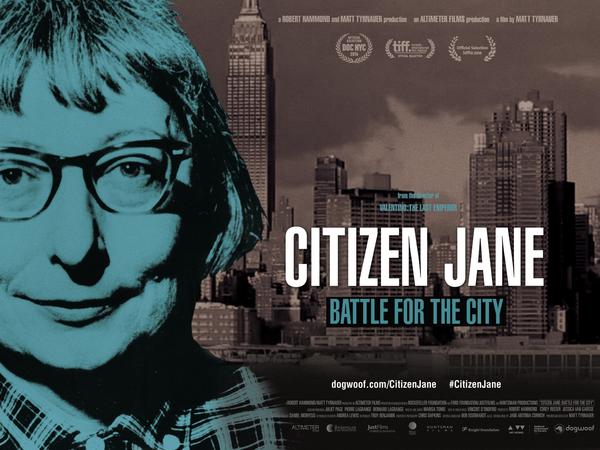

I first met Jane Jacobs on an airplane. Not literally. While flying over the Atlantic Ocean, on a return trip from London, I noticed, as I flipped through the airline’s digital film library, a feisty-sounding documentary called Citizen Jane: Battle for the City. I watched the film and, in the process, wound up loving Jane Jacobs. How could I not?

There is a winning, almost punk-rock ethos in the attitude and long career of Jane Jacobs. In 1961, she was a community activist, with no college degree. A wife and mother living in Greenwich Village, a self-taught journalist whose beat was the urban environment, she took a look at city planning practices and didn’t like what she saw. So she did something about it. Jacobs attacked not just the prevailing wisdom of recognized authorities, in the now-classic The Death and Life of Great American Cities—which I checked out of the library almost as soon as I landed—but she went on to fight and defeat the biggest, baddest planner of the 20th century: Robert Moses. (The documentary necessarily simplifies the narrative into a steel-cage match between Jacobs and Moses, even though the truth was obviously more complicated. But how else, beside dramatic framing, are you going to keep people watching a film about city planning for an hour and 32 minutes? For more on film's narrative, read my interview with Citizen Jane’s director and producer.)

The irony of an airborne introduction to Jacobs: So much of our legendary urbanist’s accomplishments involved bringing the design of cities down to earth from the soaring views of modernists, such as the Olympian personage who called himself “Le Corbusier.” A passage from Le Corbusier’s Aircraft will suffice: “[I]t is as an architect and town-planner—and therefore as a man essentially occupied with the welfare of his species—that I let myself be carried off on the wings of an airplane, make use of the bird's-eye view, of the view from the air, to which end I directed the pilot to steer over cities.”

Such high-flying philosophy repulsed the hero of Citizen Jane. In the film, we hear the Cynthia Ozick-looking Jacobs say, of the attitude of conventional city planners: “There’s a prudishness, a fear of life, a wish to direct things from some uncontaminated refuge that is part and parcel of their bad plan.” Notice the awesome dichotomy she creates: Jacobs casts herself as the sensualist and realist, and the planners as a bunch of frightened spinsters. She plunges into the living breathing world of the city, and invites you to join her on street level.

Indeed, Jacobs says that the civic powers-that-be are fooling themselves, that their learning is little more than a kind of defensive faith, pathetically unmoored from the real. Planners, she writes, “have gone to great pains to learn what the saints and sages of modern orthodox planning have said about how cities ought to work and what ought to be good for people and businesses in them. They take this with such devotion that when contradictory reality intrudes, threatening to shatter their dearly won learning, they must shrug reality aside.”

A true populist, Jacobs is to my mind, our most successful embodiment of Lincoln’s “government by the people, for the people, of the people.” She reminds one of Walt Whitman, who also reveled in the comprehensive detail of city life. Her insistence on specificity is so humane and so poetic. If any writer could truly understand what Whitman meant about “the blab of the pave” and “the talk of the promenaders,” who truly heard “[w]hat living and buried speech is always vibrating here,” it’d be she. Recall how she suggested the we look at city life and “liken it to the dance—not to a simple-minded precision dance with everyone kicking up at the same time, twirling in unison and bowing off en masse, but to an intricate ballet in which the individual dancers and ensembles all have distinctive parts which miraculously reinforce each other and compose an orderly whole.”

The spirit of “eyes on the street” is what we’re talking about—and it’s a poetry that Jacobs insisted we should all share. Her call for participation is larger than that, and more demanding. It isn’t enough for city folk to be consulted in the planning process; they must be completely involved. She writes:

I hope any reader of this book will constantly and skeptically test what I have to say against his own knowledge of cities and their behavior. If I have been inaccurate in observations or mistaken in inferences and conclusions, I hope these faults will be quickly corrected. The point is, we need desperately to learn and to apply as much knowledge that is true and useful about cities as fast as possible.

If you have an ounce of belief in American democracy, you’d read this and want to stand up and cheer! This might be the most reader-empowering aside that a non-fiction author has ever issued. Jacobs was actually inviting her reader to call her out on her own mistakes. From all the available evidence, she meant it to be taken seriously.

On film, Jacobs says, “I think it’s wicked, in a way, to be a victim.” She goes far beyond encouraging architects and planners to engage with end users. She insists on self-determination and complete existential engagement—from everyone in the city. The notion of equating passivity and wickedness is not for the faint of heart.

Her belief was vastly strong, and it moved others to agitate for legitimate change. In Citizen Jane, famed architectural critic Paul Goldberger says, “Jane Jacobs is one of the very first people to say the car is not supreme. The people who walk on the sidewalk are what makes the city.” Imagine a ‘60s housewife saying no to an expressway running through her New York City neighborhood—and getting the city to agree. Astonishing!

One wonders how we might cut-and-paste Jacobs’ ethos into our current moment, or if it’s even possible. Do you hear writer-led crowds demanding that cities ensure that citizen data, say, will be adequately protected, or that pedestrians, not self-driving cars, come first? No, you don’t. Today countless urbanists and designers have read Jacobs and hold her up as a hero—and a few are eager to suggest that she wasn’t entirely right—but how many of them emulate her ability to combine philosophy, writing, and activism into a single, integrated work-life? I imagine that Jane would enjoin those who, like myself, rooted for her in the documentary and read The Modern Library edition of The Death and Life in some suburban coffee shop, to ask ourselves, “Have you done enough? What have you done?”

If you believe in what she has to say, it’s not enough, not nearly enough, to admire Jacobs. She wants you to act, to have a say in public life, in the communal construction of your environment. She wants your vigorous civic involvement, and if you skip out on that, you will be shirking your democratic duty. And so: Attend planning meetings. Educate yourself. Meet your neighbors. Speak up. Get involved. And here I think not of Jacobs but of Emerson who has reminded generations of English majors, and hopefully other Americans: “Nothing can bring you peace but yourself. Nothing can bring you peace but the triumph of principles.” For all the drama in Jacobs’ life, and there was more than enough to fuel a feature-length documentary, she seems, in the final estimate, to have also achieved a great inner Emersonian peace. How are you doing on that front?