Jonathan Barnbrook is known for his socio-political inspired typefaces, among them “Mason” (a.k.a. “Manson”), “Bastard,” “Patriot,” “Nixon Script,” “Apocalypso” and “Drone.” He also designed the Grammy winning covers for David Bowie’s “Blackstar” and “The Next Day” album covers. For a designer who takes such a keen role, through type, typography, books and posters, in the political discourse this past year has left him somewhat disoriented and champing at the bit. “I have to say political work is tough for me in these times,” he told me. “Satire doesn’t work, showing people up as they are, doesn’t work, seems people don’t care.”

So, while “formulating a response and will return at some point,” in the meantime Barnbrook has taken refuge in electronic music. As is true for various designers, music and sound is a compliment to visuals and imagery, what he calls “my equal love next to graphic design.” He explains that it is a place where he controls everything, the beat, the tempo and of course the visual response.

Anil Aykan and Jonathan Barnbrook with their synthesizer.

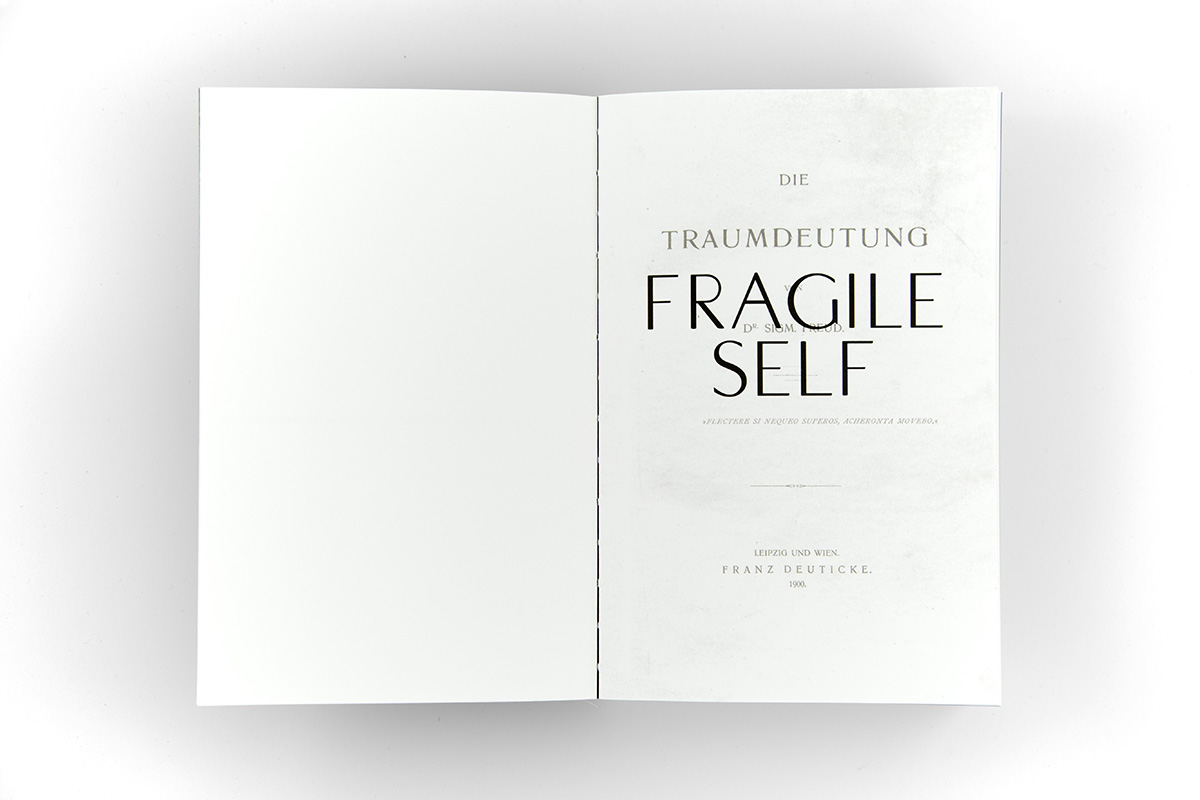

Barnbrook and his collaborator, percussionist and wife, Anil Aykan. who comprise the band Fragile Self, released their first results as an eponymous album on CD, vinyl along with a uniquely illustrated five-hundred-page book. The book is a summation of several years of work, it takes a dive into the meaning, subject, atmospheric feeling of the songs. Having looked, read and listened I can say it is a remarkable relationship between music and graphics.

Barnbrook has long been a quintessential “designer as author”, and this project simply continues his practice into another realm of authorship, visceral sensation and expression. I recently asked him to discuss this distinct yet logical inclusion to his repertoire of creative platforms

Steven Heller: How long have you and Anil been involved with electronic music and its relationship to visual art?

Jonathan Barnbrook: We have been working on it since 2010 – a very long-term project indeed! But it took that long to bring it all together in terms of making sure all of the content was right, there is a huge amount of research in this, not to mention our first foray into music which is no small task. Fragile Self is both a liberating and terrifying project – we control the content rather than using someone else’s, but also you are in a new area and putting it in front of musicians who clearly are going to judge it.

Heller: There is an affinity between visual and sound, but why did you decide to do such an elaborate graphic accompaniment?

Barnbrook: In the beginning we really wanted to have no visuals at all, just for our pure love of music to come through, but then we thought about what is unique about us that we could bring to the world of music which is completely saturated with artists and it was that bringing together of music and visuals in one form. So, they were never thought about independently from each other and we knew we could explore the project in a really thorough visual manner as well as a musical one.

Our advantage is that being designers we are well organized and could treat it as a project which had a definite outcome – which I know sounds quite disconnected emotionally, but in this case the content you are using is yourself, your emotions, thoughts and images of yourself - so it partially comes down how honest you are with the responses to the world and makes those decisions of rejecting or accepting something extremely difficult.

Heller: What does the music provide you with that graphic design and type does not?

Barnbrook: Well having said the things that helped being a designer there is definitely a lot that made us uncomfortable, there is a whole new world of theory and composition. The most exciting difference though is the spontaneity of live performance music, just often depends on making music at a certain moment and when it goes well it is the most fantastic feeling. That process is the opposite of the endlessly edited design work we do. Also, with this project, although we think about the audience – we are the main audience so there is nobody trying to modify our ideas here.

Heller: It seems to me both disciplines require a lot of discipline?

Barnbrook: We are obsessed with how the music is made. It’s all pure electronic music created on mainly modular synthesizers. If you don’t know them, they break down a conventional synthesizer into separate parts. Meaning you can mix different ways of making sound with generative composition — it is a real playground of noise and song making.

Heller: You say it is a life-long passion. How or why did you go for design, shall we say, first?

Barnbrook: My interest in design came from music, I was obsessed with record covers from the age of 13. If an album cover was good it enhanced my experience of the music, it felt like covers were important extensions of that intangible feeling when music triggered something inside you. The discovery of the album cover came with the realization that there is someone who creates that — that there is such a job as a graphic designer exists. I kind of became obsessed with typography as soon as I started college and then followed that. It strangely wasn’t until I started working with [David] Bowie that I felt like I could bring something to the area of record cover design (not a bad person to start with!). The actual music making started when I met Anil, because she had been involved in bands and was also passionate about music. We compliment each other really well; definitely the result is more than just the sum of parts.

Heller: Tell me a bit more about the narrative foundation for this music and book?

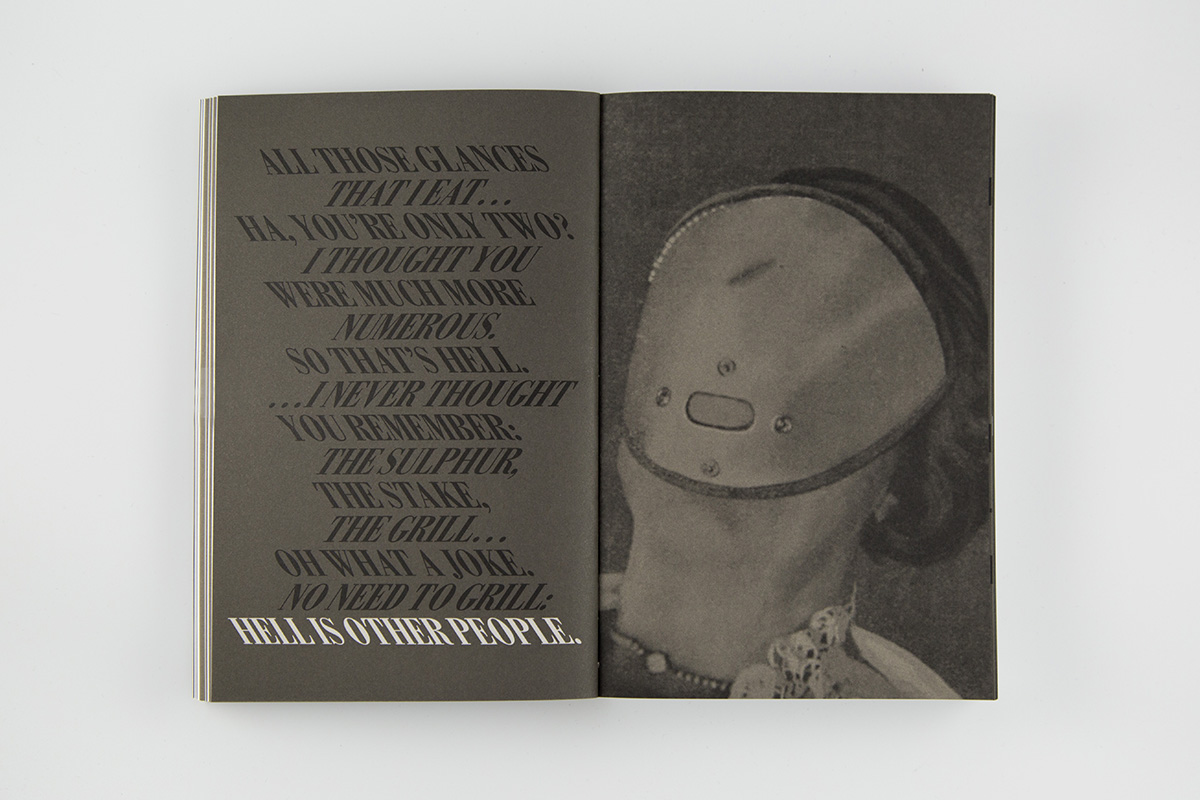

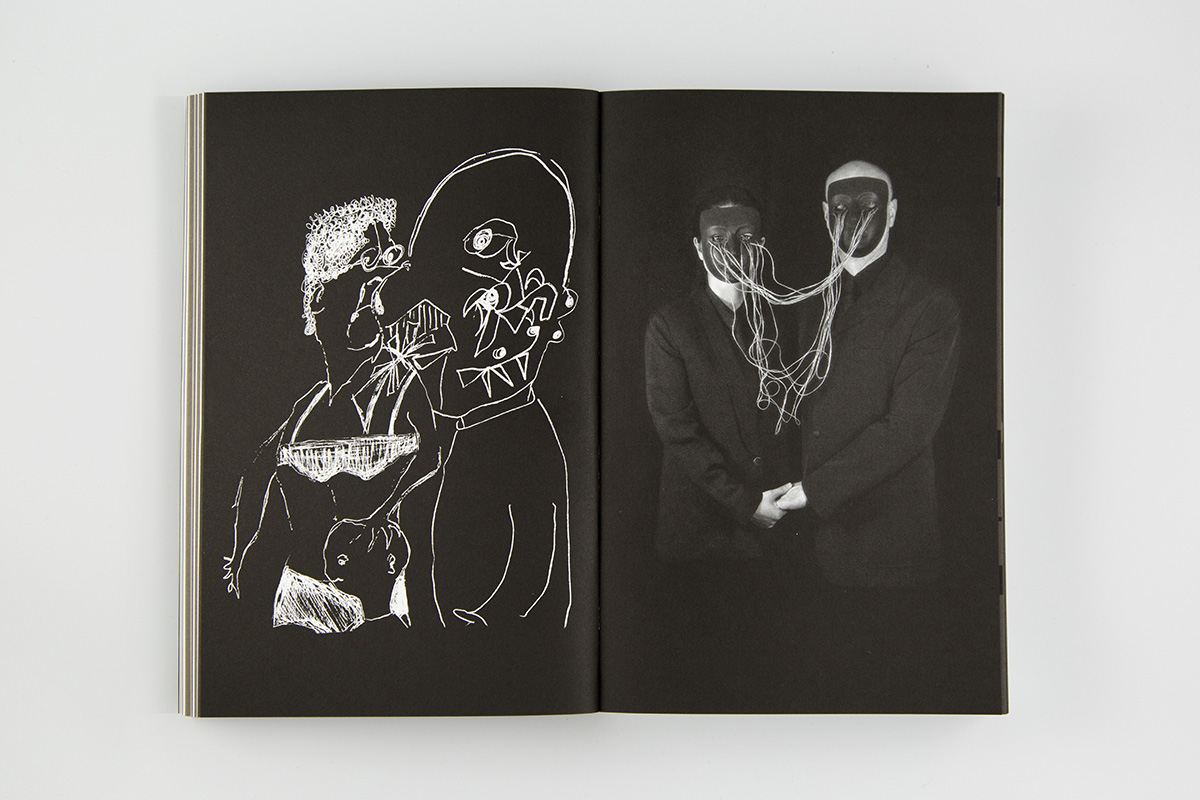

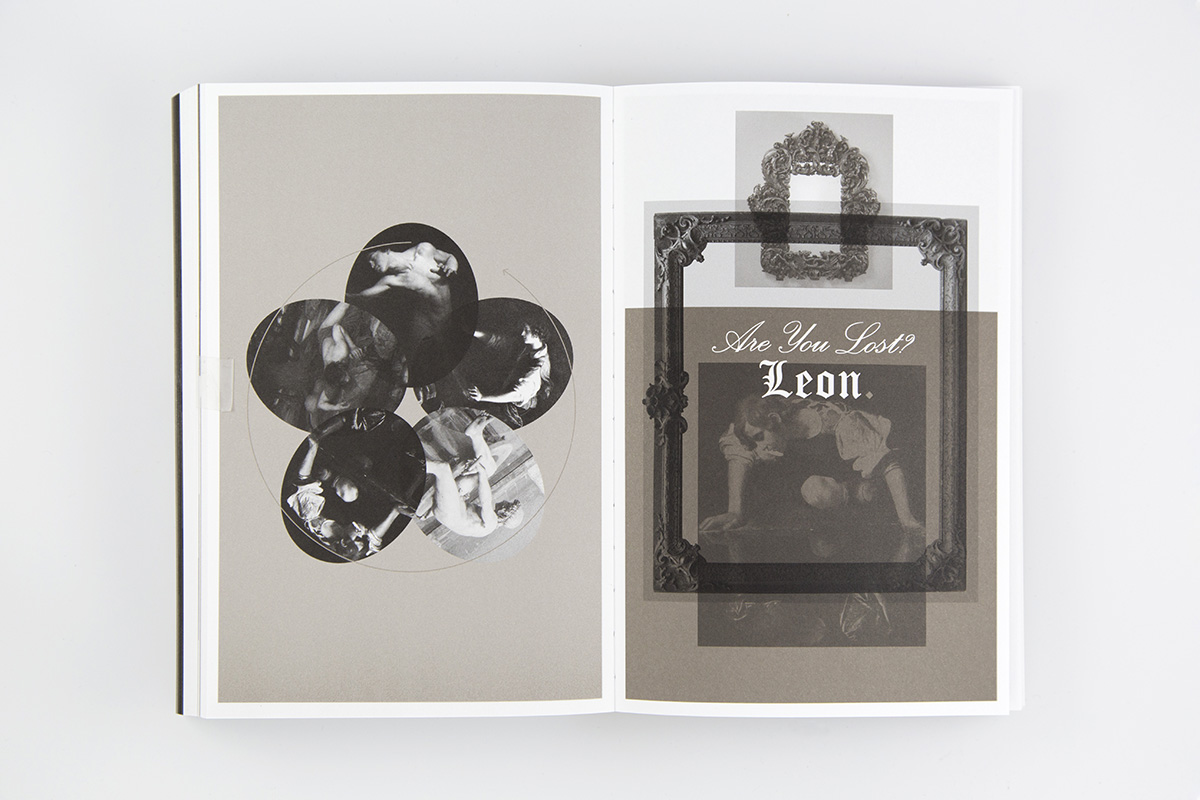

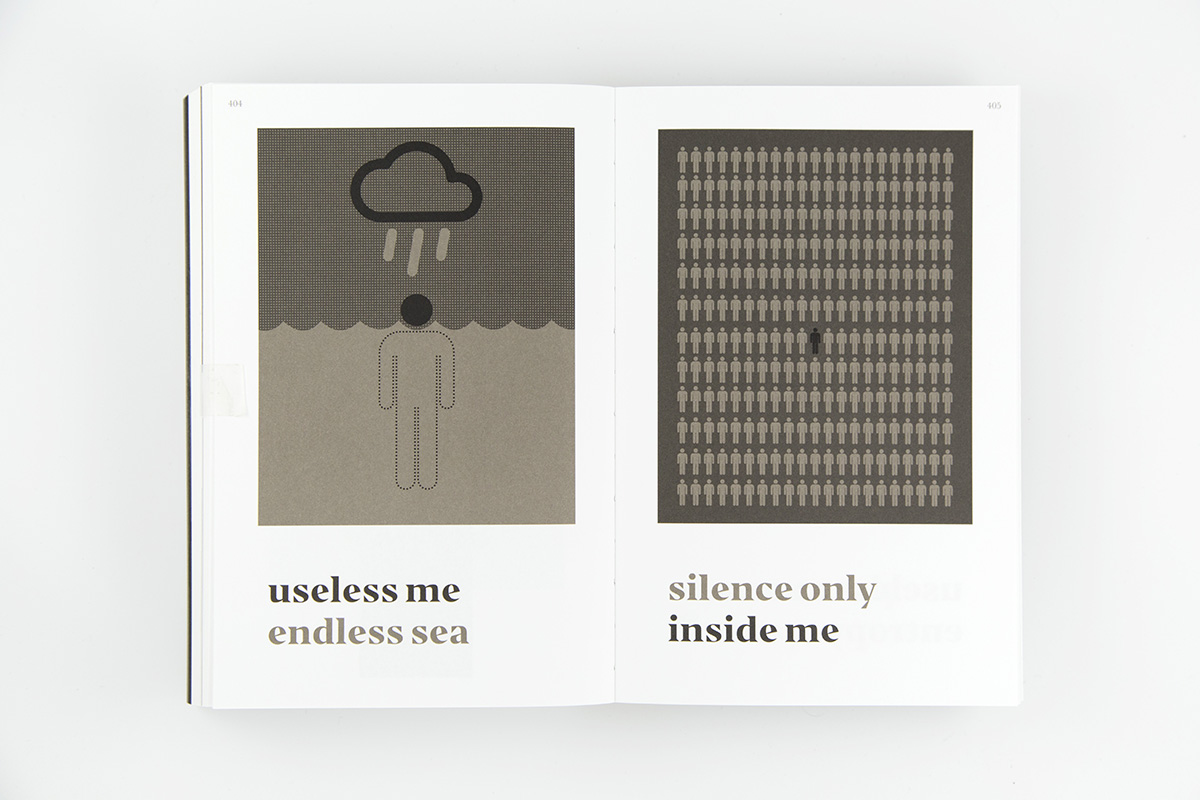

Barnbrook: There are a lot of themes about mental health but they are treated in a more poetic or observational form. Anil studied psychotherapy and I started to read the books she was reading for her course too. It was a hugely creative time for both of us understanding how the subconscious can affect creativity, how people who have a different perception of the world can be hugely creative and how we have treated creatives and people with mental health issues throughout history. Somewhere within that is a path to being more creative yourself and understanding what it is to be a human with a fully-fledged identity that is a result of all of the experiences of your past. Music tells us something about the truth of what being a human being is and I hope in our own way we have revealed a truth too in this project. This is mixed with creative visual responses to the subject matter of the songs, and also research into for instance specific lines of lyrics. For instance, the German phrase ‘Einmal ist keinmal’ appears in one of the songs and all of the meanings and uses are explored in the book. This is all part of the space – 500 pages – that the book gives us to go on tangents and put things in which are part of the indirect meaning of the songs.

Heller: That psychological component is very familiar. I have written a bit about the surrealistic quality of the Apperception Tests that I took when I was a kid. . .

Barnbrook: We have tried to do a few new things including the first authorized use of the ‘Apperception Test’ images. Which is a psychological test that using images whose meaning changes dependent on the mental health of the person who looks at them. There is also a collaboration with the artist Peter White from Bethlem Gallery, London – they work with former mental health patients from the South London and Maudsley NHS Trust. The book also includes a huge amount of literary references that needed permission sought and original photography that all needed.

Heller: What are your present and future plans for this?

Barnbrook: Since we started this project, it felt like it has become another part of both of us, part of our relationship. So, I don’t imagine it will ever stop, this is not like a design project where you have solved a problem and then you move onto the next project. Here it is much more about expressing what we feel in a very pure form. It is sometimes difficult, we argue about the way songs are composed, what images should be used but also the way of working together is something of the most enjoyable that I have done, it feels like a new universe to explore create every ‘atom’, the sound waves, the sequences, the visuals, the lyrics. It’s very exciting.