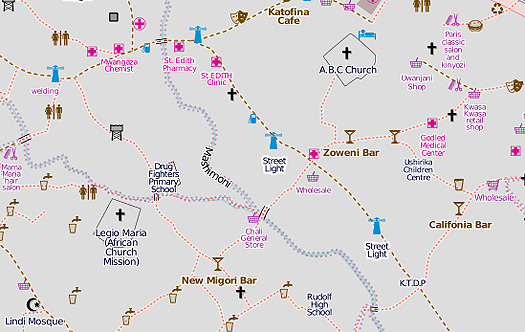

Detail of current Kibera plan, from mapkibera.org.

Wise visitors to Kibera take a guide. Sprawling across more than 500 acres on the edge of Nairobi, the settlement ranks as one of Africa’s largest and poorest slums. Up to a million people are thought to live in the jumble of garbage-strewn streets and alleys, the exact lay-out changing from week to week. Finding a path though the shantytown presents a constant challenge even to locals. Maps produced by the Kenyan authorities or aid agencies are often outdated or unavailable to the public.

That’s why the Map Kibera project was launched last year. In just a few months, a team of local youngsters using simple handheld GPS technology has produced an online open-source digital map of the entire district. On offer: all the information that the inhabitants — rather than the authorities — need for survival. One look at the map shows the location of a range of landmarks and facilities from water pumps, latrines, schools and health clinics to shops, churches or mosques.

But the map is intended for much more than just navigation. Its backers see the project as part of a wider drive to empower the slum’s residents, providing the data they need to deal with the authorities and take control of their own future. A second phase in the map’s development, now almost complete, envisions its wider use as a media tool that push awareness of its problems. Says Erica Hagen, who co-founded Map Kibera with digital mapping expert Mikel Maron: “This isn’t just about access to information, it’s about creating that information itself.”

Already it’s taken much painstaking work. With help from local Kenyan partners and initial funding from the U.S. group JumpStart International, the organizers trained a team of cartographers to create the map, pinpointing the sites that they considered important, then uploading the data onto the computer. By using the techniques of OpenStreetMap, a free user-edited map of the world, data can be constantly updated — just as on Wikipedia.

Some likely benefits are clear. A better knowledge of Kibera’s geography should help the government or NGOs to fill the gaps in the basic services — whether it’s sanitation or electricity — that the community badly needs. At the same time, the project has helped the spread of technological know-how in Kibera and built links with Nairobi’s tech community by enlisting its help. Says Hagen: “There is quite a vibrant technological community in Nairobi but it hadn’t really reached to the kids in Kibera.”

That could be just the start. In the latest phase of the project the Map Kibera team has been collecting more specific information in four areas, health, security, education and water, that can also be accessed through the map. Want details of the local health clinic? The map will be able to help.

Bolder still, the organizers hope that the smart multimedia use of the map will promote community journalism and engage the public’s interest. The online Voice of Kibera service collects local media, including video, and reports submitted through the web and via SMS, linking stories to a specific point on the map. To feed the flow of information, more young people have been trained in the use of video and editing software. Only when its voices and stories are heard outside the community, say the organizers, will Kibera be truly on the map.