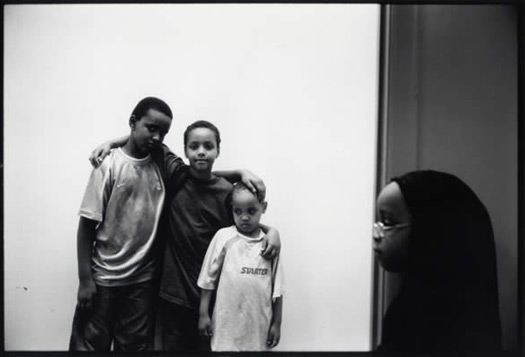

Abdi Roble, Huda Quran School, Columbus, OH, 2004

When photographer Abdi Roble witnessed the mass flight of his fellow Somalis he knew he must help. In the 1990s tens of thousands were fleeing their homeland to escape a vicious civil war, and many were reaching America where Roble had already settled. “I looked at myself and thought: you have a roll of film and a camera: this can be your philanthropy.” His plan: to create a record of the experiences of his people at a critical time in their history, a gesture that would help to ease the pain of loss and migration.

The result is a unique portrait of a community, possibly the first attempt in history to capture the process of migration and resettlement while it’s still under way. Since launching the Somali Documentary Project in 2003, Roble has taken more than 100,000 photographs showing every aspect of Somali migrant life, whether riding the bus, studying the Quran, celebrating a wedding or shopping in a local Somali-run store in Minneapolis. Settings range from the butcher’s shop to the mosque; from the kitchen to the classroom.

It’s an undertaking of epic scale. Bitter conflict continues in Somalia — Roble makes a point of excluding its divisive politics from the project — and at least a million Somalis are now thought to be living outside their homeland. America’s largest Somali community, Minneapolis, numbers up to 100,000 people, while Columbus, Ohio, where Roble lives, is home to some 40,000. Many are still trapped in the refugee camps of Kenya.

In the search for material, Roble has traveled not only across America but also to Europe and Kenya. To supplement his pictures, he has enlisted Ohio-based writer Doug Rutledge, who has carried out thousands of interviews which will be used as captions or stored to provide a lasting chronicle. Most are eager to help. Says Roble: “Every individual has a story to tell especially those who you encounter here in America, but they also want to share those stories so that they can become one collective story.”

But the project aims to be much more than an archive. Roble, who came to America as a cash-strapped immigrant in 1989, believes it can also help to break down barriers between the incomers and the host community. With money raised from a range of non-profits as well as donations from individuals Somalis, he has staged exhibitions and lectures across America. “Fear is about the unknown and one thing we emphasize is the importance of at least getting people to talk to each other. We all have so much in common. Every parent just wants a safe neighborhood and a good education for their children.”

For Roble, it’s an absorbing task with no obvious end while the migration continues. Over the last four years, he has worked full-time on the project. With Routledge, he has already produced a book, The Somali Diaspora published in 2008, and next year his pictures will form part of exhibitions in New York and Washington, sponsored by the Open Societies Foundation. And his ambitions go still further. In time, Roble hopes to establish a museum, probably in Columbus or Minneapolis, dedicated to the diaspora, a permanent memorial to lasting exile.

When photographer Abdi Roble witnessed the mass flight of his fellow Somalis he knew he must help. In the 1990s tens of thousands were fleeing their homeland to escape a vicious civil war, and many were reaching America where Roble had already settled. “I looked at myself and thought: you have a roll of film and a camera: this can be your philanthropy.” His plan: to create a record of the experiences of his people at a critical time in their history, a gesture that would help to ease the pain of loss and migration.

The result is a unique portrait of a community, possibly the first attempt in history to capture the process of migration and resettlement while it’s still under way. Since launching the Somali Documentary Project in 2003, Roble has taken more than 100,000 photographs showing every aspect of Somali migrant life, whether riding the bus, studying the Quran, celebrating a wedding or shopping in a local Somali-run store in Minneapolis. Settings range from the butcher’s shop to the mosque; from the kitchen to the classroom.

It’s an undertaking of epic scale. Bitter conflict continues in Somalia — Roble makes a point of excluding its divisive politics from the project — and at least a million Somalis are now thought to be living outside their homeland. America’s largest Somali community, Minneapolis, numbers up to 100,000 people, while Columbus, Ohio, where Roble lives, is home to some 40,000. Many are still trapped in the refugee camps of Kenya.

In the search for material, Roble has traveled not only across America but also to Europe and Kenya. To supplement his pictures, he has enlisted Ohio-based writer Doug Rutledge, who has carried out thousands of interviews which will be used as captions or stored to provide a lasting chronicle. Most are eager to help. Says Roble: “Every individual has a story to tell especially those who you encounter here in America, but they also want to share those stories so that they can become one collective story.”

But the project aims to be much more than an archive. Roble, who came to America as a cash-strapped immigrant in 1989, believes it can also help to break down barriers between the incomers and the host community. With money raised from a range of non-profits as well as donations from individuals Somalis, he has staged exhibitions and lectures across America. “Fear is about the unknown and one thing we emphasize is the importance of at least getting people to talk to each other. We all have so much in common. Every parent just wants a safe neighborhood and a good education for their children.”

For Roble, it’s an absorbing task with no obvious end while the migration continues. Over the last four years, he has worked full-time on the project. With Routledge, he has already produced a book, The Somali Diaspora published in 2008, and next year his pictures will form part of exhibitions in New York and Washington, sponsored by the Open Societies Foundation. And his ambitions go still further. In time, Roble hopes to establish a museum, probably in Columbus or Minneapolis, dedicated to the diaspora, a permanent memorial to lasting exile.