LEFT TO RIGHT: Costruzioni by Marta Giunpero; Earthscraper by Simone Giai; Urbanism - Struttura G0053 by Giulio Vesprini.

“A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not even worth glancing at, for it leaves out the one country at which Humanity is always landing. And when Humanity lands there, it looks out, and, seeing a better country, sets sail. Progress is the realization of utopias.” — Oscar Wilde, cited by Rutger Bregman in his recent book, Utopia for Realists and how we can get there (Bloomsbury)

Walter Benjamin, Patrick Geddes, Jane Jacobs, and other urban luminaries, who’ve spent their lives studying “cities in evolution”* adorned the oversize banners that hung in the foyer of Turin’s Centrale Lavazza, last October. Replete with quotes, data, maps, illustrations, and fun facts cited from unlikely media sources, those visionaries were the preamble to last fall’s Utopian Hours festival theme: “8 Billion Cities.” They’re also Luca Ballarini’s personal utopian heroes (and mine too in fact), thinkers and doers that inspire this Turin-born and -based global architect turned creative director extraordinaire, official city mover and shaker. Through TorinoStratosferica, the nonprofit he cofounded with Giacomo Biraghi, also co-director of Utopian Hours, and with the support of his agency Bellissimo, Luca Ballarini’s built this engaging rendez-vous since 2017. Urbanists, planners, creative entrepreneurs, elected officials, flâneurs, climate activists are invited, they’re people from around the world who walk the walk, and not just talk the talk.

LEFT TO RIGHT: Ctrl + I - Invertire il mondo by Alvar Aaltissimo; Vertical retreat by Andrea Mongia; Cycling in my city by BR1.

The event isn’t just a bunch of talks, it’s become a timely catalyst and platform for Luca’s own creative placemaking initiatives and his guests’ in Torino—the #3 city in Italy, which, in 2008, became the first World Design Capital. This fall, the festival aimed to refocus utopia on a definition of urbanity that favors a human-centered approach, rather than define it by physical/architectural construct—learning from the shifts the recent pandemic operated on our psyche and overall perception of our habitat. “Imagination is the ultimate frontier for humanity,” declares Luca Ballarini.

If the crucial question remains ‘where to live,’ the impetus is to overcome the superficial oppositions to which we have become addicted, to strive to be both “urbanites” and a human species capable of listening to Nature—to reconcile the tensions between city quitters and city revivers. —Luca BallariniA city reviver, that’s what Luca is about. I met him for the first-time last year in Turin while on a UNESCO Creative Cities of Design tour about sustainable mobility. I had coproduced a workshop for the Saint-Etienne Cité du design in partnership with the city of Turin’s urban planning department, to explore soft mobility models, vegetalization and pedestrian solutions for its city center. I reached out to Luca who invited me to visit his Precollinear park project. An old tramway path turned public park over the river Pô that attempted to improve the well-being of inhabitants, contribute to the reduction of pollution and heat while offering a common living space during COVID and beyond. Quite a program. Design by the people for the people.

Subsequently, I invited Luca last spring during the 12th International Design Biennale in Saint-Etienne, wherein I produced and moderated Fix, Flux +Flow: rebuilding the imaginaries of mobility, a one-day conference about sustainable mobility. There, Luca discussed the power of the designer-citizen, able to drive change in cities by mobilizing its inhabitants—lots of architecture students preferably—as exemplified in his Precollinear project. He often talks about the image of the city, the new visual “postcard” that makes a city desirable with clearly identified destinations and recognizable markers. In turn, these new iconic spots help define the identity of a place, and its overall rep’. Luca warns about the importance of care and caretaking of public spaces and urban regeneration projects—especially those that try to rekindle our communion to nature—one of the main themes of this year’s festival.

LEFT TO RIGHT: Il Quinto Stato (Torino, 2133) by CityMaybe; Torino come Arcipelago by Fabio Alessandro Fusco; HyperSwarmingCity by Riccardo “Akasha” Franco-Loiri.

The Utopian Hours festival was polished, highly efficient, diverse, and friendly. It was held in the striking new venue of La Centrale at Nuvola Lavazza, an old power station part of the Lavazza complex, revisited by architect Cino Zucchi. With this same architect and the very same intent to regenerate old heritage building with meaning and purpose Stratosferica recently announced it was part of the winning team for the Cavallerriza project. The international competition, sponsored by Fondazione Compania di San Paolo, plans to turn Cavallerriza, the 17th C. royal palace stables into a new cultural, social and educational hub right in Torino center. The Utopian Hours event mixed perspectives from activists, tech investors and entrepreneurs, Co2 emission fighters, urbanists and elected officials. As a bonus, the festival organizers took us on tours of some of the most iconic venues of the Piedmont capital, such as Lingotto, house of automotive superpower Fiat, whose rooftop and famous pista was recently turned into a public park à la High Line, courtesy of landscape architect Benedetto Camerana. Again, dichotomy resolved and urban nature on display for all.

I sat with Luca Ballarini late last year to reflect on how his work and Utopian Hours’ program converge to change-making in the city, his city, Turin. But also, all the other capitals he often visits and interacts with, thanks to inspiring programs and speakers, lots of whom, New Yorkers I had a chance to meet personally, or even work with in my life in NYC—such as Majora Carter, Scott Francisco, Amanda Burden (those contemporary visionaries that will adorn one day oversized banners)…

Laetitia Wolff: About utopia: in the daunting moment we live in, utopia has never been so needed. Utopian Hours is the title of your festival since 2017 but do you think it particularly resonates this year? Has something changed, if so what?

Luca Ballarini: With every edition of the festival, we’re building on this understanding that Utopian Hours is not to stand “against,” rather it’s about finding a way out, a way forward, utopia is a solution-seeking endeavor. Utopia means either the best place or the other place—our job is to suggest a new recipe for building better places, we engage the people who are building them. In the first edition we tried to debunk what we knew and perceived around us, but now, professionals and practitioners show they are very aware of what’s going on. COVID has accelerated the need to do something for humanity but also for city and policy makers, who can no longer ignore the complex ecosystems we live in and have to provide answers within them. Are you an optimist? Are you a pessimist? We never use the word dystopia—but that’s not the point. There are elements in everything we perceive as utopia that could be dystopian, if pushed too far, too progressive, too one-sided. Think Truman Show. You could say that every great utopian went too far—Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright, Buckminster Fuller. Utopia is more about accepting the idea of building a better place.

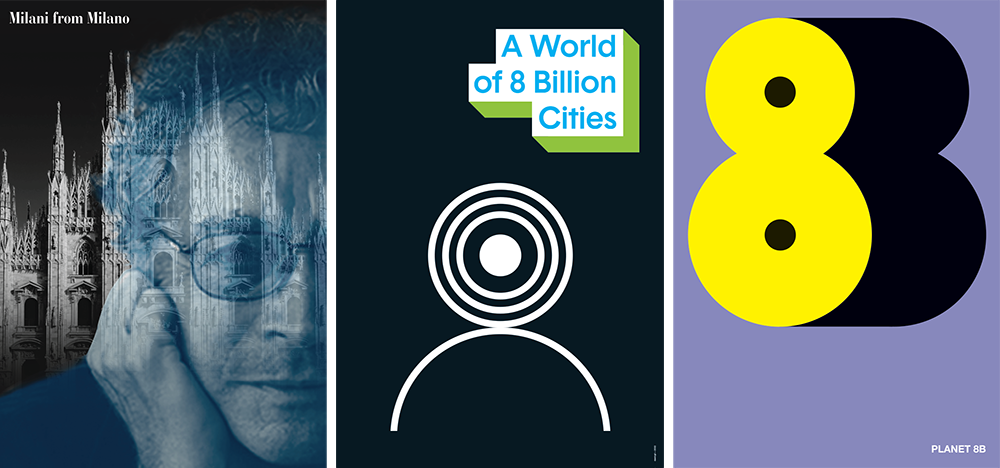

LEFT TO RIGHT: Milani from Milano by Armando Milani; A World of 8 Billion Cities by David Gil; Planet 8B by Francesco Dondina.

LW: “From city making to citizen making,” accompanies this year’s edition title “A world of 8 billion cities.” Can you elaborate on how you envisioned this shift and how some of your guest speakers illustrated this idea?

LB: Our framework is there to inspire a reflection, not to make people adhere to it necessarily. “A World of 8 Billion Cities” made people understand that there was something exciting, but also something wrong. The shift is from cities to people. The city is a concept, a state of mind, as we are becoming an urban species. Our ultimate goal is to be urban; we’re training our mind to be urbanite. Making cities isn’t just a niche or industry concern, all humanity is going to be urban, so we ought to be better citizens. Is it about a mental state or the environment we live in? Is it a way to envision things, attitudes, behaviors? Media and government talk a lot more about urban sprawl than the fact that we are becoming an urban species. And while we, at Stratosferica, become aware of our symbiosis with nature, and try to bring nature into our built environment, we remain profoundly humanists, not naturalists. As our slogan says, “cities are mental weapons” created by humans both to replicate on Earth our interpretation of the cosmos, and to oppose to the forces of Nature. The solutions come from living with it, and open our consciousness to it, not by letting Nature prevails over human intervention, as some may think.

LW: Perfect segue: Your guest Scott Francisco, founder of Cities4Forests, whose mission is to help cities around the world connect with and invest in forests, announced a new deal with the city of Turin. Can you explain how you use Utopian Hours as a catalyst to accelerate the adoption of these innovative models in your city, what’s going to happen next in Turin with Cities4Forests?

LB: Cities4Forests had seen our work at the COP 26 in Glasgow. Last April, we built tables, chairs, stools, and food stands for the Precollinear park, working with conservation timber from eastern Gabon thanks to Cities4Forests’s Partners Forest Program. It was a pilot project that demonstrated our ability to manage smoothly hundreds of volunteers, and subsequently we obtained additional funds. This winter, we brokered a Memo of Understanding with the city of Turin, working with the Deputy mayor in charge of riversides and green spaces, getting a new 75,000 Euros grant from their Partners for Forest program. Together with the city we’ve decided where to allocate this money that will benefit Stratosferica to support a new creative placemaking project on Corso Farini, not far from Precollinear and near the Campus Luigi Einaudi designed by Norman Foster. It’s a tree-lined, 800-meter-long artery, divided in 3 sections, which runs along old gasometers, enormous, iconic steel structures dating back to 1862. With this new creative placemaking effort, you can imagine the potential, it still looks very run down now, but I believe we can make it an appealing place, with a pavilion container as bar, like we did for Precollinear, all in wood. It’ll be nice!

LW: The 8 Billion Cities festival featured a fun format wherein special guests are invited to walk the city freely to bring back fresh ideas for city improvement. Over the years have you built upon their feedback? Have you tried to implement some of those Urban Explorers’ suggestions?

LB: The Visiting Urban Explorers format has been featured in the festival since the very beginning. All 17 of the guest explorers have been filmed, all their videos are available on YouTube. The rules of the game: they’ve never been to Turin before, are left for 3-5 days alone to wonder, explore by themselves and discover the city. Some are more successful than others, some are ephemeral, intangible, purely conceptual or too difficult to implement, others just bring back banal suggestions, but we’ve never tried to implement their ideas. Typically, we try to implement projects that have a potential to be sponsored and sustained long-term by other stakeholders. What could be interesting is to spread them out in other cities: the balcony idea of Alizé Carrère, this year, who suggested to refresh the city by greening individual balconies, for instance, was very easily replicable.

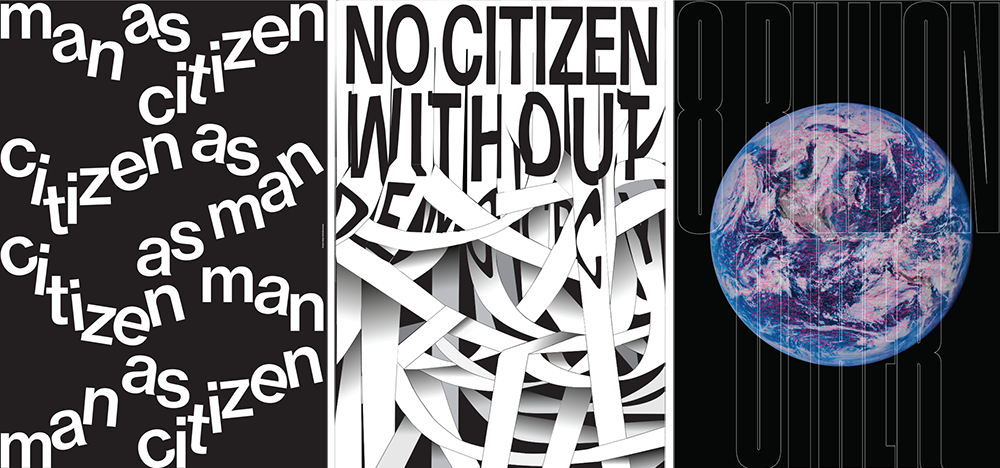

LEFT TO RIGHT: Man as citizen, citizen as man by Giulia Boccarossa; No citizen without democracy by Giulia Cordin; 8 Billion other by Sheldon.studio.

LW: “Placemaking is about changing the perception citizens have of their own city,” said guest speaker Amanda Burden, formerly New York city planner during the Bloomberg administration. What is it you wish to change about Turin, how does that apply to your projects and vision for your city?

LB: Perception at the core of what we’ve been doing since 2017. I cannot stand the legacy of some of those close-minded, bourgeois Turinese and how they relate to their city, ignorantly obsessed with failure, decline, and bad luck. They are the opposite of being great ambassadors for a city which is beautiful, and that most foreigners consider the best hidden gem of Italy. What we need to do is change the storytelling! At some point, some people thought that Precollinear felt like it belonged to another city, as if they didn’t deserve it. But it’s slowly changing, we are becoming better at communicating about Turin. I’m hopeful.

Solutions may come from the basic needs of people but also from their aspirations. You can change things at small scale, and still have a very big impact. —Luca BallariniLW: “Are architectural utopian visions truly providing ecological solutions?” provocatively questioned one of your city explorers, of Alizé Carrère of National Geographic.

LB: Architects are interested in building things, they like to be builders, and not always symbiotic with the environment and the who live around and in these buildings. I’m personally more Geddesian.*** Increasingly, I think of shrinking my own scale. Ecological solutions are not often embedded in those utopian visions, I agree with Alizé. The media talk a lot about Neom, The Line in Saudi Arabia – but come on, how far can you go into dystopia!?

LW: “Is poverty a cultural attribute, and what are you looking for in a community you desire?” asked South Bronx activist Majora Carter. And righteously so, she points to the assumptions we all have towards lower-income neighborhoods, and how those attitudes perpetuate social injustice. How did her presentation resonate with you in Europe, in Italy particularly where migrants are a polarizing subject in political debates, what lessons can you pull from her provoking analysis of bias in city making?

LB: Majora was one of the key points in the festival, we loved her presentation! Unfortunately, professionals who work here in Turin in the fields of social work, migrant welcome policies, and urban regeneration were not in the audience - they might have their own bias about how to deal with underserved communities in this country. The lesson we can pull from Majora Carter’s statement could: let’s continue to work with people, talk, walk, relate to them, build relationships by understanding their lifestyles, habits and wishes, and try to connect them with the present we live in. Solutions may come from the basic needs of people but also from their aspirations. You can change things at small scale, and still have a very big impact.

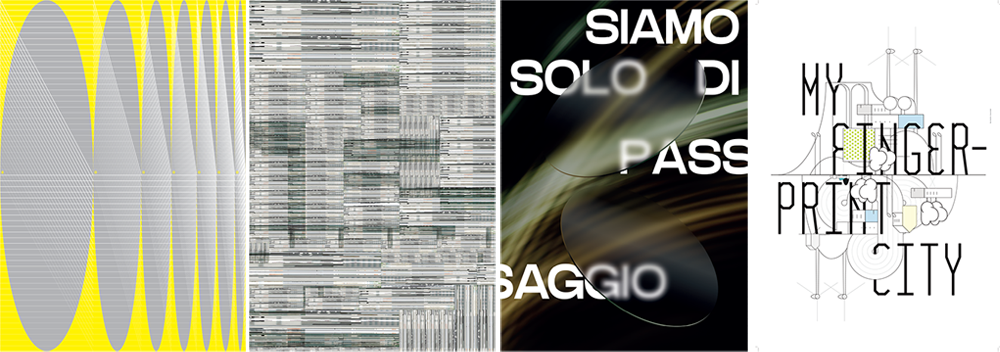

LEFT TO RIGHT: Una tecnica sottile by Filippo Papa; Deeper by Collettivo Rumore; Siamo solo di passaggio by Valentina Alga Casali; My fingerprint city by Marco Tortoioli Ricci + Francesco Gubbiotti.

LW: You firm Bellissimo produces a lot of a graphic design and branding, do you have an open call for posters at each of the Utopian Hours edition? Tell us more about this year’s 8 Billion edition.

LB: We wanted to bring more visual aspects in the festival, bring in the graphic design community, because everything is visual in the end, to convey messages and show that all disciplines are interlaced. At the core of what Utopian Hours aspires to be is the power of visuals, the festival is image-heavy. Images are so important to make people understand solutions, and also appeal to young people. Thirty years from now, they’ll be the ones to see the urban changes at play today. We should appeal to them first.

NOTE: * Cities in Evolution, an Introduction to the Town Planning Movement and to the Study of Civics, by Sir Patrick Geddes, 1915

The design posters selection was coordinated in collaboration with AIAP the Italian association of visual communication.