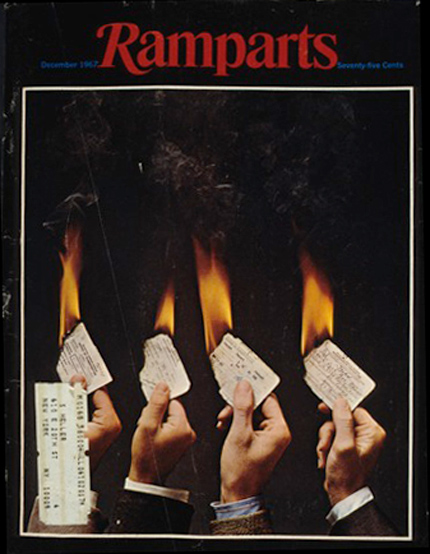

Ramparts, December 1967

Few American magazines are agents of change. Most are chroniclers of their time and place, lightning rods rather than lightning.

By the beginning of World War II, the press, and magazines in particular, were propaganda tools, whether they liked it or not, whose chief goal was to influence public opinion in support of the status quo. Even during the McCarthy era, despite some intrepid attempts to influence politics and society, magazines did not challenge popular perceptions or habits in any meaningful way. Then came Ramparts in the mid-1960s.

Marking the end of post-war puritan American values, a younger generation that had been raised on the sour milk of McCarthyism reinvigorated periodical publishing. Ramparts on the West Coast was the clarion of new aesthetics, politics and social mores. It exposed CIA involvement in American colleges and universities and reintroduced muckraking to American journalism. In providing alternatives to the dominant culture, Ramparts nurtured the New Left's emerging sensibilities, which for better or worse helped foment the revolutionary spirit of the time.

By the beginning of World War II, the press, and magazines in particular, were propaganda tools, whether they liked it or not, whose chief goal was to influence public opinion in support of the status quo. Even during the McCarthy era, despite some intrepid attempts to influence politics and society, magazines did not challenge popular perceptions or habits in any meaningful way. Then came Ramparts in the mid-1960s.

Marking the end of post-war puritan American values, a younger generation that had been raised on the sour milk of McCarthyism reinvigorated periodical publishing. Ramparts on the West Coast was the clarion of new aesthetics, politics and social mores. It exposed CIA involvement in American colleges and universities and reintroduced muckraking to American journalism. In providing alternatives to the dominant culture, Ramparts nurtured the New Left's emerging sensibilities, which for better or worse helped foment the revolutionary spirit of the time.

Ramparts, February 1966

Ramparts was not on the cutting edge of design in the way that, say, Emigre was in the 1980s and 90s. Rather, with its bookish, 19th-century conceits, it conformed to classical design verities, the most important of which was legibility. Dugald Stermer, Ramparts's art director from 1964 to 1970, explained that the magazine’s restrained format, in contrast with an anarchic approach, "lent more credibility to what must have seemed then like hysterical paranoid ravings of loonies."

Founded in 1962, Ramparts was originally published by Edward Keating, a lawyer who had sunk a private fortune into a magazine that he described as having an anti-clerical, liberal Catholic bias. Those early issues of Ramparts, which Stermer suspects was named for the "ramparts we watched," looked like a college literary magazine with unrelated typefaces, ill-crafted illustrations and unsophisticated layouts. Despite Ramparts's oppositional stance, Keating was not a basher, but rather a concerned citizen who saw aspects of America turning sour. He also realized after a few issues that all the world's ills could not be blamed entirely on the influential conservative cleric Cardinal Spellman of New York, and so he turned his attention to the burgeoning Civil Rights movement and took on the political right wing.

The early Ramparts represented the "soft wing" of the left. Yet the stance began to change when Warren Hinckle III, then Ramparts's promotion director, and Howard Gossage, a veteran San Francisco advertising man and member of the Ramparts advisory board, gradually took control away from Keating. Eventually Hinckle was named editor and Robert Scheer, a young investigative journalist, was hired as foreign editor. The former, who was not allied with any political movement, was a muckraker in the William Randolph Hearst tradition and viewed sacred cows as moving targets; the latter, a skeptic of all isms, uncovered and sourced the earliest stories about CIA involvement in the Vietnam War and on American college campuses just prior to the emergence of a national anti-war movement. Scheer had, in Stermer's words, "this remarkable curiosity into the halls of power. He did not have the revulsion for it that most on the left did, and so doggedly trailed stories that neither the mainstream nor the left had any interest in examining." With Hinckle's taste for muck and Scheer's news instinct, Ramparts began to publish important stories on subjects ignored by most of the national media.

Founded in 1962, Ramparts was originally published by Edward Keating, a lawyer who had sunk a private fortune into a magazine that he described as having an anti-clerical, liberal Catholic bias. Those early issues of Ramparts, which Stermer suspects was named for the "ramparts we watched," looked like a college literary magazine with unrelated typefaces, ill-crafted illustrations and unsophisticated layouts. Despite Ramparts's oppositional stance, Keating was not a basher, but rather a concerned citizen who saw aspects of America turning sour. He also realized after a few issues that all the world's ills could not be blamed entirely on the influential conservative cleric Cardinal Spellman of New York, and so he turned his attention to the burgeoning Civil Rights movement and took on the political right wing.

The early Ramparts represented the "soft wing" of the left. Yet the stance began to change when Warren Hinckle III, then Ramparts's promotion director, and Howard Gossage, a veteran San Francisco advertising man and member of the Ramparts advisory board, gradually took control away from Keating. Eventually Hinckle was named editor and Robert Scheer, a young investigative journalist, was hired as foreign editor. The former, who was not allied with any political movement, was a muckraker in the William Randolph Hearst tradition and viewed sacred cows as moving targets; the latter, a skeptic of all isms, uncovered and sourced the earliest stories about CIA involvement in the Vietnam War and on American college campuses just prior to the emergence of a national anti-war movement. Scheer had, in Stermer's words, "this remarkable curiosity into the halls of power. He did not have the revulsion for it that most on the left did, and so doggedly trailed stories that neither the mainstream nor the left had any interest in examining." With Hinckle's taste for muck and Scheer's news instinct, Ramparts began to publish important stories on subjects ignored by most of the national media.

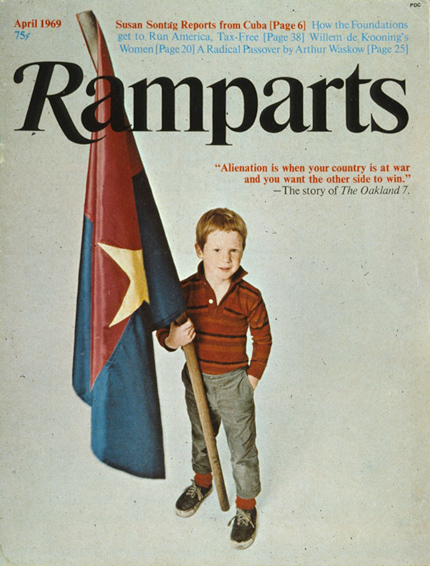

Ramparts, April 1969

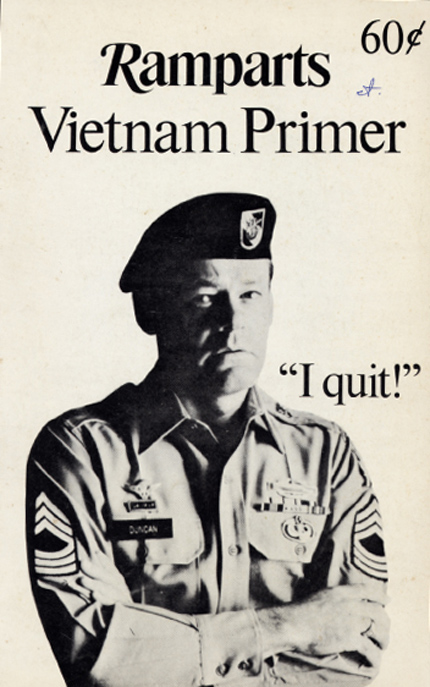

One of Ramparts's most controversial stories was the confession of a Green Beret sergeant who quit in protest of the secret war in Vietnam. Ramparts drew material from other disaffected government and military personnel whose consciences had been bothering them, but who at that time — a few years before the Pentagon Papers story broke in The New York Times — couldn't air their grievances in major newspapers. Indeed the mainstream press was skeptical of anti-government attacks, and more or less followed an "America, love it or leave it" stance. Stermer recalls that Ramparts's goal was to "just raise hell," though journalistic accuracy remained of paramount importance.

In addition to the Church and the State, Ramparts's favorite enemy was liberals. It criticized the anti-communist ideology of liberal Democrats, which it claimed was more extreme than that of Republicans. Eisenhower may have cautioned against the military industrial complex and "the potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power" in the hands of hostile states, but it was Kennedy and Johnson who presided over the Bay of Pigs and the Vietnam War. Some of Ramparts's choicest mid-sixties attacks were therefore leveled at Johnson and at Bobby Kennedy, who was seen as an ideological extension of his older brother.

In addition to the Church and the State, Ramparts's favorite enemy was liberals. It criticized the anti-communist ideology of liberal Democrats, which it claimed was more extreme than that of Republicans. Eisenhower may have cautioned against the military industrial complex and "the potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power" in the hands of hostile states, but it was Kennedy and Johnson who presided over the Bay of Pigs and the Vietnam War. Some of Ramparts's choicest mid-sixties attacks were therefore leveled at Johnson and at Bobby Kennedy, who was seen as an ideological extension of his older brother.

Although Ramparts's circulation was low compared to mainstream magazines such as Life and Look, it maintained a skeptical voice towards attitudes about power and sexuality. Yet Ramparts was not a blind follower of dogma or a passive agent of ideology. As Stermer insists, "We never took anything, not even our own side, at face value." Its editors, older than the average members of the young left (Scheer and Stermer were 31 in 1967), did little to encourage the emerging drug or rock-and-roll cultures, though they did devote an entire issue to an analysis of psychedelia. In short, says Stermer, "We were skeptical of the hippies and diggers, but did not go out of our way to criticize them either, since they weren't the enemy."

Ramparts was nationally distributed on the newsstands of the largest metropolitan areas of America. Given such visibility there was a mandate to look inviting and provocative. Stermer used Times Roman almost exclusively, with dingbats and Scotch rules for accents. The style may have been far from radical, but it was unusual at the time to use book design tropes for a magazine and it went on to influence Rolling Stone (Jann Wenner, a former Ramparts editor, copied Stermer's grid for his first issues) and New York. Having worked as an illustrator, Stermer knew how to entice commissions from known artists despite the magazine's pauper-like fees. He lured Edward Sorel into Ramparts by offering him a monthly visual column — "Sorel's Bestiary" where famous people were portrayed satirically as animals. He commissioned many members of Push Pin Studios, including founders Seymour Chwast and Milton Glaser, though they risked undermining their relationships with the mass market through association with a left-leaning journal. Robert Grossman did one of his best Johnson caricatures for Ramparts, and Paul Davis executed a number of covers, including one of South Vietnam's First Lady (technically, the president's sister-in-law) Madame Nhu, as a cheerleader for an investigative report into CIA recruitment of operatives for clandestine work in Vietnam.

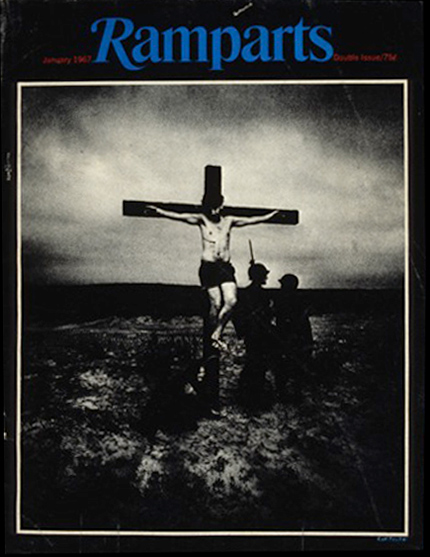

Ramparts, January 1967

Stermer proudly recalls two coups: The first was hiring Ben Shahn out of veritable retirement to do a portrait of the early anti-war senator J. William Fulbright. The second was commissioning Norman Rockwell to paint a portrait of Bertrand Russell: "I thought it would be terrific to have one great man in his seventies paint another in his nineties. Though Rockwell balked at first, apparently his son convinced him that we were more important than the Saturday Evening Post." As art director, Stermer also had a say in editorial direction, which allowed him uncharacteristic leeway in developing stories and features — both visual and text essays.

Ramparts's investigative stance required strong political covers, such as the John Heartfield–like photomontages by Carl Fischer, who at the same time was collaborating with George Lois on his legendary covers for Esquire.

Ramparts covered the waterfront but its twin preoccupations were war and racism. Vietnam turned the two focuses into one. While America was struggling to preserve democracy in Southeast Asia, a race war was raging on the streets of Los Angeles, Newark and Detroit. To shepherd coverage of domestic strife, Ramparts hired Eldridge Cleaver (who was introduced to the Black Panthers while at Ramparts and later became the minister of information of the Black Panther party). Editors at Ramparts helped him to publish his autobiography Soul on Ice. Ramparts also provided the burgeoning Black Panther movement, which was then a small paramilitary group in Oakland, with a national voice. Its cover story on Mohammed Ali explained for the first time why the "brown bomber, black beauty" became loyal to Elijah Muhammad. Over at the Evergreen Review, Barney Rosset, who had early on been interested in colonialism and African independence, fought his own war against racism by publishing books by black authors like LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka), the first edition of Alex Haley's Autobiography of Malcolm X, and Franz Fanon's landmark works on white colonialism.

Ramparts's investigative stance required strong political covers, such as the John Heartfield–like photomontages by Carl Fischer, who at the same time was collaborating with George Lois on his legendary covers for Esquire.

Ramparts covered the waterfront but its twin preoccupations were war and racism. Vietnam turned the two focuses into one. While America was struggling to preserve democracy in Southeast Asia, a race war was raging on the streets of Los Angeles, Newark and Detroit. To shepherd coverage of domestic strife, Ramparts hired Eldridge Cleaver (who was introduced to the Black Panthers while at Ramparts and later became the minister of information of the Black Panther party). Editors at Ramparts helped him to publish his autobiography Soul on Ice. Ramparts also provided the burgeoning Black Panther movement, which was then a small paramilitary group in Oakland, with a national voice. Its cover story on Mohammed Ali explained for the first time why the "brown bomber, black beauty" became loyal to Elijah Muhammad. Over at the Evergreen Review, Barney Rosset, who had early on been interested in colonialism and African independence, fought his own war against racism by publishing books by black authors like LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka), the first edition of Alex Haley's Autobiography of Malcolm X, and Franz Fanon's landmark works on white colonialism.

In addition to race and war, Ramparts ran some of the earliest investigative reports on the environment, such as "America the Raped" (May 1967), which warned of the destruction by the Army Corps of Engineers of America's ecosystems. Ramparts extolled the virtues of left-wing Catholics and their unique role in the civil rights and anti-war movements. It published frequent stories attempting to unravel the the Kennedy assassination conspiracy, much of which was used as source material for Oliver Stone's 1991 film JFK. And it gave unprecedented coverage to the Middle East and earned the anger of pro-Israeli factions among the left for taking an anti-Zionist stance in various articles.

Fearless in its coverage, Ramparts was no stranger to legal hardships. The most threatening came when Stermer arranged a 1967 cover shoot with Carl Fischer that showed his and three other staffers' hands holding their burning draft cards — a symbolic gesture of nonviolent resistance to a war that broke at least two federal laws. In executing the cover, he broke a statute known as the Disrespect Law (it commonly referred to the burning of money or the flag). This act of defiance on the part of a national magazine forced the government to empanel a federal grand jury to investigate a possible indictment. While Stermer and Scheer initially wanted to fight the case as a First Amendment issue, their counsel, a Washington lawyer and football team owner, William Bennett Williams, refused to let his clients risk imprisonment, and persuaded them to plead not guilty should an indictment be handed down. In the end, however, Williams pulled strings with his friend Lyndon Johnson, one of the bitterest Ramparts' enemies, to squash the investigation — suggesting that strings can always be pulled, revolution or not.

In contrast to the underground press, which even at most political favored hi-jinx over journalism, Ramparts and Evergreen Review were serious advocates of investigative reporting and critical commentary in the service of social activism. But they were also businesses that could not exist unless the balance sheet was balanced.

Warren Hinckle III attempted to kill Ramparts in 1969 and reform it under the title The New Ramparts. He failed (though a few years later published a few issues of a Ramparts clone, Scanlons) and left Stermer and Scheer to shepherd the magazine. At the time, collectivization was in the air and the Ramparts staff wanted a greater say in the magazine's direction. A palace coup succeeded in ousting Scheer. Although Stermer was asked to remain, "presumably because only I knew how to get the magazine out," he also left. Ramparts was then edited until 1975 by a committee, which included David Horowitz, Peter Collier (both of whom have become vocal neo-cons), David Kolodney, Patricia Shell and Peter Stone.

Ramparts has been dead for almost two decades, but to look back at it now is not an exercise in nostalgia. Rather than a document of the sixties' rights and wrongs, successes and failures, it is a monument of activist publishing. Now that the end of magazines is nearer, Ramparts stands out as one to remember.

In contrast to the underground press, which even at most political favored hi-jinx over journalism, Ramparts and Evergreen Review were serious advocates of investigative reporting and critical commentary in the service of social activism. But they were also businesses that could not exist unless the balance sheet was balanced.

Warren Hinckle III attempted to kill Ramparts in 1969 and reform it under the title The New Ramparts. He failed (though a few years later published a few issues of a Ramparts clone, Scanlons) and left Stermer and Scheer to shepherd the magazine. At the time, collectivization was in the air and the Ramparts staff wanted a greater say in the magazine's direction. A palace coup succeeded in ousting Scheer. Although Stermer was asked to remain, "presumably because only I knew how to get the magazine out," he also left. Ramparts was then edited until 1975 by a committee, which included David Horowitz, Peter Collier (both of whom have become vocal neo-cons), David Kolodney, Patricia Shell and Peter Stone.

Ramparts has been dead for almost two decades, but to look back at it now is not an exercise in nostalgia. Rather than a document of the sixties' rights and wrongs, successes and failures, it is a monument of activist publishing. Now that the end of magazines is nearer, Ramparts stands out as one to remember.