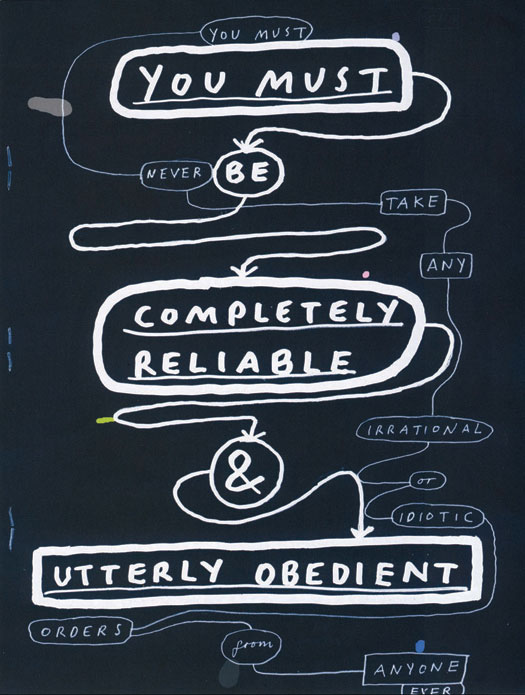

Flow chart by Paul Davis

London: an early morning train in January. I’m trying to concentrate on my book but the guard is making banal announcements and I read the same paragraph over and over again. He urges us to be careful on the icy platforms. He is concerned about our safety and comfort.

I’m on my way to see the artist Paul Davis. The train announcer would make a good target for one of Davis’ satirical drawings. It’s easy to imagine him savaging the guard’s unctuous pronouncements and the feigned concern for our safety and comfort.

Davis has asked me to write the introduction to his latest book. I told him I didn't want to write about the usual stuff — art school, his first job, wrangles with clients. He agreed and suggested we go for a walk instead. We decide to stroll around Shoreditch in East London — a once raffish and impoverished district but now a fashionable area of bars, galleries, and design studios. We could be flâneurs for a day, I said. I could be Boswell to his Johnson.

We agree to meet in a café. We are the only customers. We gossip and trade design industry tittle-tattle. Davis moans cheerfully about gutless commissioners who say they like his work and then get other people to rip off his style. He’s not bitter — just uncomprehending. He describes a life of furious productivity. He works every day, he says. Drawings pour out of him; he draws as often as other people draw breath. Later, at his studio, he shows me the outcome of all this effort.

We leave the café. The iron-grey sky has been replaced with the brittle yellowy brightness of winter sun. Davis talks about money. His girlfriend. His recent attack by an unknown assailant. I knew Davis had been attacked but I didn't know the details. When mutual friends had spoken about it, they had winced sympathetically in a way that discouraged questions.

I asked him what had happened. Davis had left his flat early one evening. As he walked down the street he was smashed on the head by someone who came up behind him. He only remembers waking up in an ambulance. The attacker had severed an artery in his head. His face was a mask of blood.

He has no idea why he was attacked. The same thing has happened to other people he knows. He thinks it might have been a gang initiation rite: young bloods earning their stripes by performing acts of random violence. Davis seems an unlikely victim. He’s wiry and agile. Not an obvious target. But evidently someone thought it was a good idea to bash him on the head. Safety and comfort.

He has no idea why he was attacked. The same thing has happened to other people he knows. He thinks it might have been a gang initiation rite: young bloods earning their stripes by performing acts of random violence. Davis seems an unlikely victim. He’s wiry and agile. Not an obvious target. But evidently someone thought it was a good idea to bash him on the head. Safety and comfort.

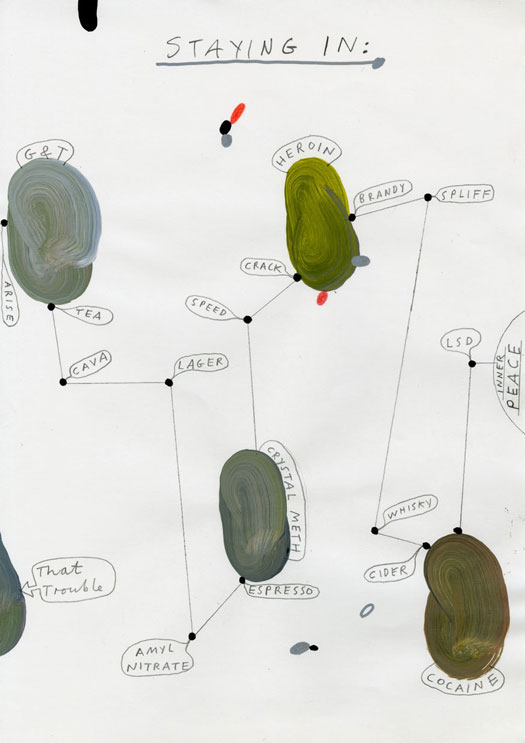

Flow chart by Paul Davis

We pound the pavements around Brick Lane. We pass galleries and shops. Everywhere we look we see signs of the bo-ho gentrification that is turning Shoreditch into just another precinct of tourist London. Suddenly Davis points to the myriad of tiny ovals of flattened chewing gum that cover the roads and pavements. There are thousands of them momentarily illuminated and glowing in the January sun. It’s like a shoal of tiny flat fish veering into view. He says that these blobs — and the blobs that appear on his retina — inspired the ovals that populate his newer work.

After Brick Lane we push eastward. We stand in the bandstand at Arnold Circus. Davis smokes a cigarette. The elegant redbrick housing estates are quiet. No one is on the street. No traffic. We wander over to the Rochelle School, a Victorian building with separate entrances for boys and girls. It’s no longer a school, but if you listen carefully you can hear the ghostly yelping of hundreds of children from the nearby Boundary Estate — one of the first housing estates in the world and a legendary place in East London social history.

The Rochelle School is now a fashionable spot inhabited by a gallery, an artist’s agent, a design studio, a publisher and — where the old bike shed once was — a swanky eatery. Davis meets someone he knows professionally. They tap dance around each other — he charming and eager, she wary and distant.

We head back to Davis’s studio. We look through his work. I am reminded of his furious energy and productivity as sheaves of sketches are laid out on every available surface. I notice that the drawings are full of brightly coloured ovals, and I remember the chewing gum.

We go to lunch at a nearby restaurant. Afterwards we head off in opposite directions. I keep thinking of Davis’s attack. I can’t get the thought of it out of my head. I hear footsteps behind me. I look round. It’s a gangly youth. In his hand he carries a gun. But it's only a cup of coffee with a plastic lid. Safety and comfort on the streets of London.

We pound the pavements around Brick Lane. We pass galleries and shops. Everywhere we look we see signs of the bo-ho gentrification that is turning Shoreditch into just another precinct of tourist London. Suddenly Davis points to the myriad of tiny ovals of flattened chewing gum that cover the roads and pavements. There are thousands of them momentarily illuminated and glowing in the January sun. It’s like a shoal of tiny flat fish veering into view. He says that these blobs — and the blobs that appear on his retina — inspired the ovals that populate his newer work.

After Brick Lane we push eastward. We stand in the bandstand at Arnold Circus. Davis smokes a cigarette. The elegant redbrick housing estates are quiet. No one is on the street. No traffic. We wander over to the Rochelle School, a Victorian building with separate entrances for boys and girls. It’s no longer a school, but if you listen carefully you can hear the ghostly yelping of hundreds of children from the nearby Boundary Estate — one of the first housing estates in the world and a legendary place in East London social history.

The Rochelle School is now a fashionable spot inhabited by a gallery, an artist’s agent, a design studio, a publisher and — where the old bike shed once was — a swanky eatery. Davis meets someone he knows professionally. They tap dance around each other — he charming and eager, she wary and distant.

We head back to Davis’s studio. We look through his work. I am reminded of his furious energy and productivity as sheaves of sketches are laid out on every available surface. I notice that the drawings are full of brightly coloured ovals, and I remember the chewing gum.

We go to lunch at a nearby restaurant. Afterwards we head off in opposite directions. I keep thinking of Davis’s attack. I can’t get the thought of it out of my head. I hear footsteps behind me. I look round. It’s a gangly youth. In his hand he carries a gun. But it's only a cup of coffee with a plastic lid. Safety and comfort on the streets of London.