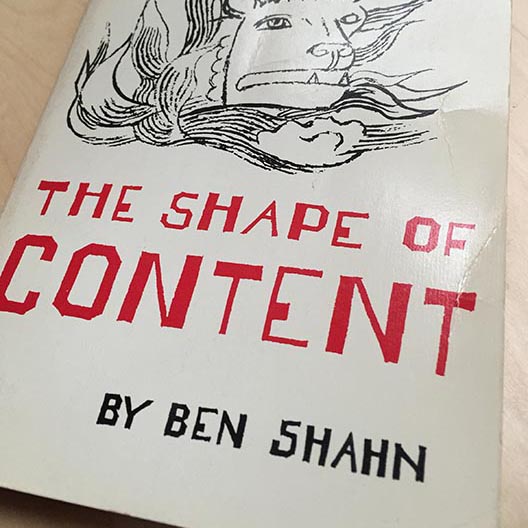

If you are going to read one thing this summer (or now), I suggest an essay in Ben Shahn’s The Shape of Content titled “Biography of a Painting.” It is not just about painting but rather about what is involved in making an image—a heartfelt image. Since designers are image-makers and storytellers, the ideas that Shahn, who was a poster artist, print maker, book illustrator, photographer, and painter from the 20s through the 60s, addresses regarding the symbolic composition of his painting entitled “Allegory” is not only relevant to the muse-driven elite but to all “applied” or commercial artists and designers.

The Shape of Content is a anthology of lectures given at Harvard in 1957. They address all matters pertaining to his creation of art. Yet “Biography” explains how art is not immune to the issues of the day, or the news of the moment, but rather is a tool of communicating information and critiquing the world. It is about a painting Shahn made in 1948 that was directly inspired by a news article about a Chicago fire in which “a colored man had lost four children.” Shahn was asked to make drawings to accompany a “Concise reporatorial account of the event.” The item was written with the dispassion that was common with such reportage, but after Shahn had acquired all the facts and viewed the visual record of the fire he decided on a different course.

“It seemed to me,” he wrote, “that the implications of this event transcended the immediate story; there was a universality about man’s dread of fire, and his suffering of fire.” He further noted that it suggested that racial injustice played a role in this event that “had its own kind of universality.”

Shahn accounts for why, instead of literally portraying the event, he decided to develop a symbolic framework. “The narrative of the fire,” he wrote, “had aroused in me a chain of personal memories.” There were two significant fires in his own life, one when he was a boy and the town where he lived had burned down. The other that “left its mark upon me and all my family, and left its scars on my father’s hands and face, for he had clambered up a drainpipe and taken each of my brothers and sisters and me out of the house one by one, burning himself painfully in the process.” As I read this passage, I recalled being pulled out of the top fifth floor of my burning apartment building, which killed my next door neighbor.

Shahn describes in vivid terms how he developed symbolic imagery to express the feelings the news and memories evoked—and his search to find the right image. But it is not just a biography of this painting, the essay is about the harshly critical response from a New York critic and friend who attacked its technique and intention, going so far as to reject it as political propaganda. Shahn admitted that “Allegory” “is an idea painting. It is also a highly emotional painting, and I hope that it is still primarily an image, a paint image.” With great eloquence he explained that painting (like design) is not a limited medium. “Painting can contain the politician in a Daumier, the insurgent in a Goya, the suppliant in a Masaccio.”

There are many who say design should stick to serving the client and designers should keep politics out of what they do. For anyone who wants to read a inspiring account of why this is a short sighted view, I highly recommend “Biography” as a way a trigger this charged conversation.