Marcel Breuer’s Wassily Chair, 1927-28. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Herbert Bayer

Having known the word in my youth — first as the moniker of the big-haired 1980s proto-goth punk band from the UK, then as a shorthand term for certain modernist architecture — I was thoroughly shocked the first time I encountered images of the Bauhaus School complex, taken during the 30-year period of East German decay following World War II. That vast swaths of culture had been left to languish under hard-line regimes throughout the Eastern Bloc was no surprise (many towns in the former East Germany had a derelict appearance until only recently). But that the Dessau campus of an institution so renowned and of such significance across all disciplines of art and design had been left to crumble was jolting.

Thanks in large part to achieving status as a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage Site in 1996, the Bauhaus buildings in Dessau (and the institution’s previous home in Weimar) have been preserved and restored. Yet while the school’s paragons are routinely venerated for their individual contributions to their respective fields, celebrations of the school’s influential and pioneering impact as a singular body are still mystifyingly lacking.

Having known the word in my youth — first as the moniker of the big-haired 1980s proto-goth punk band from the UK, then as a shorthand term for certain modernist architecture — I was thoroughly shocked the first time I encountered images of the Bauhaus School complex, taken during the 30-year period of East German decay following World War II. That vast swaths of culture had been left to languish under hard-line regimes throughout the Eastern Bloc was no surprise (many towns in the former East Germany had a derelict appearance until only recently). But that the Dessau campus of an institution so renowned and of such significance across all disciplines of art and design had been left to crumble was jolting.

Thanks in large part to achieving status as a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage Site in 1996, the Bauhaus buildings in Dessau (and the institution’s previous home in Weimar) have been preserved and restored. Yet while the school’s paragons are routinely venerated for their individual contributions to their respective fields, celebrations of the school’s influential and pioneering impact as a singular body are still mystifyingly lacking.

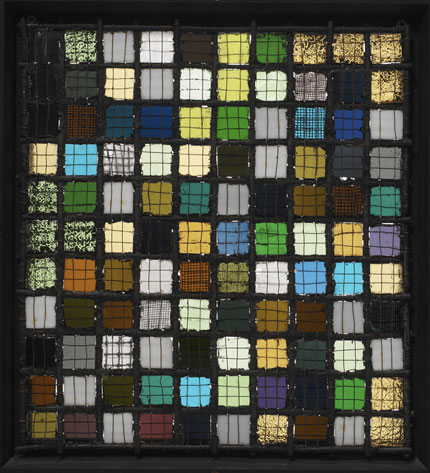

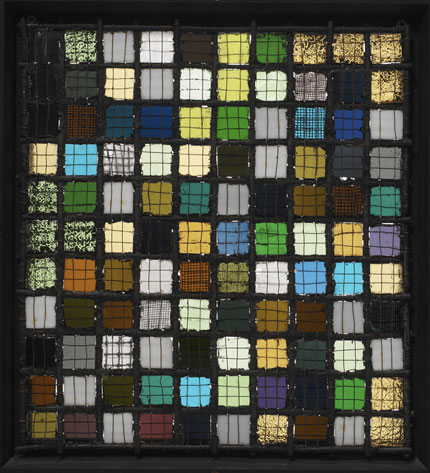

Josef Albers’ Gitterbild (Lattice picture, also known as Grid mounted). c. 1921. Albers Foundation/Art Resource, NY. Photo: Tim Nighswander © 2009 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

A case in point: The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition “Bauhaus 1919–1933: Workshops for Modernity,” running until January 25 in the museum’s sixth-floor Tisch Gallery. The new exhibition is the first update since “Bauhaus 1919–1928,” MoMA’s first, last and only comprehensive examination of the school, which was mounted nine years after the museum opened. Not since 1938 has the Bauhaus been appreciated as a singular historic organ by New York’s highest modernist institution. To boot, that lone summary exhibition wasn’t a summary at all, as it excluded the final five years of the school’s existence.

As if that bizarre, seven-decade sin of omission weren't striking enough in plain numbers, consider that MoMA regards the Bauhaus as a massive influence on its own founding and development. Alfred Barr, Jr., the museum’s original director and an art historian, wrote to Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius that the former’s brief visit to Dessau shortly before MoMA opened was "one of the most important incidents in my own education."

That the original “Bauhaus 1919–1928” show excluded one-third of the institution’s duration (even though it wasn’t presented until five years after it closed) can be attributed to Barr’s personal relationship to Gropius, who organized the exhibition to cover only his own tenure as Bauhaus director. But MoMA’s subsequent 70-year lacuna on the Bauhaus is just plain baffling.

The reason for the long wait? Ostensibly, it was simply an oversight. Given their stature as individual practitioners, Bauhaus artists are constantly appearing in other MoMA exhibitions, and the idea for a comprehensive show on the entire school just hadn't been pursued. Apparently it was when “Workshops for Modernity” organizer Barry Bergdoll joined MoMA three years ago as the Philip Johnson Chief Curator of Architecture and Design that the ball for a comprehensive Bauhaus show got rolling. Bergdoll and his co-curator, Leah Dickerman, are quick to point out that they don't consider the 1938 show as comprehensive, either. In its entire 80-year history, MoMA has never fully examined the Bauhaus School. Thankfully, their new exhibition includes the years under Hannes Meyer and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and captures the full spirit of the institution.

A case in point: The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition “Bauhaus 1919–1933: Workshops for Modernity,” running until January 25 in the museum’s sixth-floor Tisch Gallery. The new exhibition is the first update since “Bauhaus 1919–1928,” MoMA’s first, last and only comprehensive examination of the school, which was mounted nine years after the museum opened. Not since 1938 has the Bauhaus been appreciated as a singular historic organ by New York’s highest modernist institution. To boot, that lone summary exhibition wasn’t a summary at all, as it excluded the final five years of the school’s existence.

As if that bizarre, seven-decade sin of omission weren't striking enough in plain numbers, consider that MoMA regards the Bauhaus as a massive influence on its own founding and development. Alfred Barr, Jr., the museum’s original director and an art historian, wrote to Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius that the former’s brief visit to Dessau shortly before MoMA opened was "one of the most important incidents in my own education."

That the original “Bauhaus 1919–1928” show excluded one-third of the institution’s duration (even though it wasn’t presented until five years after it closed) can be attributed to Barr’s personal relationship to Gropius, who organized the exhibition to cover only his own tenure as Bauhaus director. But MoMA’s subsequent 70-year lacuna on the Bauhaus is just plain baffling.

The reason for the long wait? Ostensibly, it was simply an oversight. Given their stature as individual practitioners, Bauhaus artists are constantly appearing in other MoMA exhibitions, and the idea for a comprehensive show on the entire school just hadn't been pursued. Apparently it was when “Workshops for Modernity” organizer Barry Bergdoll joined MoMA three years ago as the Philip Johnson Chief Curator of Architecture and Design that the ball for a comprehensive Bauhaus show got rolling. Bergdoll and his co-curator, Leah Dickerman, are quick to point out that they don't consider the 1938 show as comprehensive, either. In its entire 80-year history, MoMA has never fully examined the Bauhaus School. Thankfully, their new exhibition includes the years under Hannes Meyer and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and captures the full spirit of the institution.

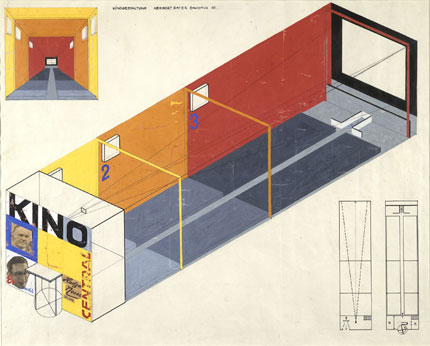

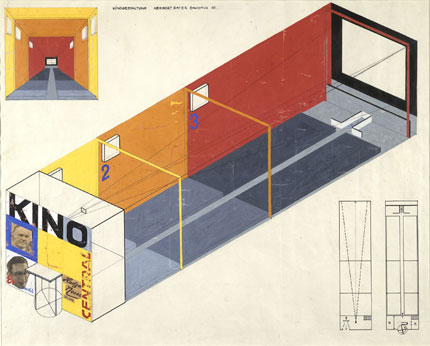

Herbert Bayer’s design for a cinema. 1924–25. Harvard Art Museum, Busch-Reisinger Museum. Photo: Imaging Department © President and Fellows of Harvard College © 2009 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

In the context of its time, the impact of the Bauhaus was seismic. No era has shaped the course of human civilization as profoundly as the 20th century, and in many ways the Bauhaus movement represents a hinge of modern history. The preceding 100 years had a progressive bent and tumultuousness previously unknown to man, and the Bauhaus rose during the hectic modernizing interim between the two World Wars, at a time when everything from domestic life to the materials that populated it was shifting. In 1900, few people outside of the largest cities in Europe and America had electricity; by the time the Bauhaus closed in 1933, they had color films, the Empire State Building, frozen foods and Scotch Tape. The school kept pace with the breakneck cadence of change, adopting new industrial materials, experimenting with production techniques for everything from imagery to housewares to homes themselves and pushing the flexibility of prefabrication. The glee with which the school adopted the rapid acceleration of artistic disciplines and mediums, and the degree to which they were targeted and eventually extirpated by mid-century sociopolitical movements, is only partially metaphorical for the century as a whole. It is not a stretch to consider the Bauhaus as the artistic distillation of the 20th century’s creativity, aspirations, experiments and failures.

As remarkable as it was in the context of the 1920s and ’30s, there should be no doubt as to the importance of the Bauhaus today. Addressing the question of whether retrospective appreciation of the school was "merely a belated wreath laid upon the tomb of brave events," Herbert Bayer and Walter Gropius stated, in the book that accompanied MoMA’s 1938 exhibition:

"Emphatically, no! The Bauhaus is not dead; it lives and grows through the men who made it, both teachers and students, through their designs, their books, their methods, their principles, their philosophies of art and education."

How right they were. With so much innovation, approaching the sprawling Bauhaus oeuvre is a complicated matter. MoMA's “Workshops for Modernity” retrospective is to be primarily framed around the chronological development of the Bauhaus, split into sections that follow the school from the 1919 founding in Weimar (the seat of the eponymous Republic, Germany’s 15-year flirtation with a legitimate liberal constitutional democracy) through the 1925 move to Dessau, and the final throes in Berlin during 1932 and 1933, where they were ultimately stamped out by the advent of Nazi rule.

In the context of its time, the impact of the Bauhaus was seismic. No era has shaped the course of human civilization as profoundly as the 20th century, and in many ways the Bauhaus movement represents a hinge of modern history. The preceding 100 years had a progressive bent and tumultuousness previously unknown to man, and the Bauhaus rose during the hectic modernizing interim between the two World Wars, at a time when everything from domestic life to the materials that populated it was shifting. In 1900, few people outside of the largest cities in Europe and America had electricity; by the time the Bauhaus closed in 1933, they had color films, the Empire State Building, frozen foods and Scotch Tape. The school kept pace with the breakneck cadence of change, adopting new industrial materials, experimenting with production techniques for everything from imagery to housewares to homes themselves and pushing the flexibility of prefabrication. The glee with which the school adopted the rapid acceleration of artistic disciplines and mediums, and the degree to which they were targeted and eventually extirpated by mid-century sociopolitical movements, is only partially metaphorical for the century as a whole. It is not a stretch to consider the Bauhaus as the artistic distillation of the 20th century’s creativity, aspirations, experiments and failures.

As remarkable as it was in the context of the 1920s and ’30s, there should be no doubt as to the importance of the Bauhaus today. Addressing the question of whether retrospective appreciation of the school was "merely a belated wreath laid upon the tomb of brave events," Herbert Bayer and Walter Gropius stated, in the book that accompanied MoMA’s 1938 exhibition:

"Emphatically, no! The Bauhaus is not dead; it lives and grows through the men who made it, both teachers and students, through their designs, their books, their methods, their principles, their philosophies of art and education."

How right they were. With so much innovation, approaching the sprawling Bauhaus oeuvre is a complicated matter. MoMA's “Workshops for Modernity” retrospective is to be primarily framed around the chronological development of the Bauhaus, split into sections that follow the school from the 1919 founding in Weimar (the seat of the eponymous Republic, Germany’s 15-year flirtation with a legitimate liberal constitutional democracy) through the 1925 move to Dessau, and the final throes in Berlin during 1932 and 1933, where they were ultimately stamped out by the advent of Nazi rule.

Eberhard Schrammen’s Maskottchen (Mascot). c. 1924. Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin. Photo: Gunter Lepkowski © Estate Eberhard Schrammen

“Workshops for Modernity’s" loose sequential organization is foremost a gesture of convenience: the school was always headed in all directions at once as a matter of purpose, with few to no true unifying principles throughout its existence. A grand experiment in completely rethinking the structure of human life as we know it through art, there was a distinct vision at its inception. As Gropius put it [emphasis his] to "create a new guild of craftsmen, without the class distinctions which raise an arrogant barrier between craftsman and artist. Together let us conceive and create the new building of the future, which will embrace architecture and sculpture and painting in one unity and which will rise one day toward heaven from the hands of a million workers like the crystal symbol of a new faith." Though that may sound communist in nature (and indeed it did to the Nazis), the Bauhaus was officially staunchly apolitical.

In short, the Bauhaus eschewed all maxims beyond simply creating objects through a unity of artistic work across all fields. The various departments of the Bauhaus were segregated in name only, and cross-pollination was the written rule. As a consequence, the output could be prolific but unexpected. Though they did create several private houses and a couple of apartment blocks, along with a government building or two, the architects who ran the Bauhaus (Gropius was succeeded as director by Hannes Meyer and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, each serving a three-year stint) delivered far less built output before the school’s closure in 1933 than one might imagine. (Oddly, there was only an official architecture department for the last six years, and beyond their own facilities in Dessau perhaps the most notable architectural design to come out of the school was a losing bid for the Chicago Tribune Tower.)

Instead of hunching over drafting tables all day, architects busied themselves with interior design (Gropius crafted iconic door handles) and furniture (Marcel Breuer’s chairs); painters sculpted (László Moholy-Nagy was an early experimenter with Plexiglas) and metalworked (Marianne Brandt reinvented the idea of the lamp and the ashtray) and theorized (Wassily Kandinsky’s book Point and Line to Plane); printmakers created jewelry (Anni Albers) and light projection apparatuses (Ludwig Hirschfeld Mack).

Unlike the hit-and-miss results of many experimental and mixed-media artists, the Bauhaus masters and students produced valuable and groundbreaking works at a breakneck pace, so much so that their names have entered the modern lexicon in iconic form. A generation before Damien Hirst had Rachel Howard painting spots for him, and some 30 years before Robert Rauschenberg “erased” Willem De Kooning, Maholy-Nagy's "Telephone Pictures" were a genesis of conceptual art in 1922. Kandinsky is generally considered the progenitor of abstract expressionism. Naum Gabo’s name is synonymous with the origins of kinetic art. Moholy-Nagy and Paul Klee were working with spray paint in the 1920s. Johannes Itten and Josef Albers mixed speculative thought and demonstrative experimentation to lay the foundations for the contemporary principles of color theory. Kandinsky, Ludwig Hirschfeld Mack, Gertrud Grunow and Kurt Schwerdtfeger were all developing early experiments on the relationship between color and sound, unwittingly making their way into later scientific research on dissonance and synesthetic composition (a 1930 print of a "visual analysis of a piece of music, from a color-theory class with Wassily Kandinsky" by Heinrich Siegfried Bormann is included in the exhibit). Herbert Bayer pioneered the now-ubiquitous use of all lowercase letters and created typefaces that were a benchmark in graphic design.

Though it may have slept on the Bauhaus for the better part of a century, to its credit MoMA has recognized the diversity of the school’s output; and for “Bauhaus 1919–1933: Workshops for Modernity,” Bergdoll and Dickerman have augmented the museum's own collection of works with contributions from the Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin, Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau and Klassik Stiftung Weimar. The result is a thoroughly impressive catalogue of works. All told there are several hundred objects in the exhibition: a host of brochures, posters and sales catalogues and a collection of postcards from a dozen Bauhaus students and faculty; all manner of mixed-media collages; textile and wallpaper samples; photographs, paintings, woodcuts and illustrations; graphic design and typography sheets; architectural plans; furniture and housewares (from chairs and lamps to a baby cradle, teapots and inkwells); marionettes, toys and chess sets; 35mm film sequences; sculptural pieces made from glass, metal, plastic and even wooden aircraft propellers; and documentation of other projects that range from stained glass windows to promotion of an International Hygiene Exhibition.

There is scant work by Mies van der Rohe (two chairs, a page from a catalogue and the marked-up architectural drawings of a student), but virtually every other prominent Bauhaus artist is well covered, with several dozen works by Klee, Kandinsky and Moholy-Nagy alone. In addition to his letterpress and typography samples, Herbert Bayer's Thuringian banknotes and a series of 1924 designs for a newspaper stand, a cigarette pavilion, a movie theater and "an illuminated advertising sphere" are particularly interesting. Also of note is the juxtaposition between the two pieces from the lawyer, theater director and painter Lothar Schreyer: one is the 1920 design for a coffin ("death house for a woman") and the other the class schedule for the 1921–22 winter semester.

The development of the Bauhaus was eclectic in both concept and deed, and the sheer variety of works in “Workshops for Modernity” deftly illustrates that fact. While some of the aesthetic trends favored by many prominent Bauhaus artists were also present in other modernist movements, the Bauhaus was distinguished by the adaptation of technology and the utilitarianism of mass production. The school was also populated by German, Swiss, American, Russian, Dutch, Austrian, Hungarian, Slovenian, Ukrainian, Czechoslovakian and Japanese artists, most of whom were already then or would eventually become luminaries in architecture, painting, interior design, typography, sculpture, photography, weaving, printmaking, color theory and education. This diversity will be front and center in “Workshops for Modernity’s" Bauhaus Lab that accompanies the exhibition, an interactive program offering a series of symposiums, workshops and classroom experiments that focus on not only the mechanics of process employed at the school but also the cultural aspect of the Bauhaus, with selections highlighting the role of women and artists of various nationalities.

Though the Bauhaus itself was located in Germany, the school was short lived and afterwards the style lived on primarily in America. Oddly, if it weren't for the Nazis the development of modernism in the United States might have been at a much slower clip. After leaving Germany, sometimes with a stop in England or Switzerland, a good number of the school’s masters and students immigrated to the United States. Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer brought the newly reorganized Harvard Graduate School of Design to prominence in architecture; László Moholy-Nagy launched the New Bauhaus in Chicago, which quickly became the Illinois Institute of Technology's Institute of Design; Ludwig Hilberseimer and Mies van der Rohe also landed in Chicago with Maholy-Nagy, the latter of the two spawning a generation of eminent architects with his "God is in the details" approach; Anni and Josef Albers took over the painting program at Black Mountain College in North Carolina and instructed the likes of Cy Twombly, Robert Rauschenberg and Susan Weil; Herbert Bayer helped the Container Corporation of America (which developed the six-pack) revolutionize product packaging and advertising before moving on to Colorado's Aspen Institute; Werner Drewes was graphic arts director for the Works Progress Administration in New York and went on to teach painting and printmaking at the Brooklyn Museum, Columbia University and Washington University in St. Louis. The list of the Bauhaus' contributions to the art of American culture is virtually limitless. In the world at large, the Bauhaus footprint is simply astounding.

In terms of contemporary style and design, the Bauhaus reigns supreme as an overarching influence even today. The school's faculty, students and subsequent practitioners have directly resulted in everything from the tallest office building in Michigan (more than half a century before designing Comerica Tower at Detroit Center, architect Philip Johnson's career was inextricably altered after he met Mies) to the title script for the iconic TV show The Jeffersons (Herbert Bayer's "Universal" typeface is perhaps the most mimicked script in design history) to that lone red wall in your yuppie friend's apartment (scattered amongst the primarily black, white and gray faces of the Dessau campus were red walls and yellow ceilings) to virtually every aspect of popularized modern design.

Without the Bauhaus, who knows what the interior shots of the Sterling Cooper offices on Mad Men would look like: there would likely be no Mark Rothko paintings and the furniture would certainly be more Frank Lloyd Wright–style wood than Mies and Breuer’s metal. IKEA probably wouldn’t exist at all, and leafing through the latest issue of Dwell magazine feels like a tour through the Bauhaus catalogue. For their new exhibition MoMA has also constructed a Bauhaus Lounge that is "furnished with chairs, tables, and couches designed by Bauhaus faculty, and offers visitors a relaxing space to further explore the creative processes of Bauhaus artists."

“Bauhaus 1919–1933: Workshops for Modernity” runs until January 25. Additional information on the exhibition can be found at http://www.moma.org/bauhaus. European readers should note that there is currently a fantastic and extensive career retrospective of László Moholy-Nagy — one of the most astonishingly versatile, influential and progressive artists of the Bauhaus collective — running until the February 7 at the Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt, Germany.

“Workshops for Modernity’s" loose sequential organization is foremost a gesture of convenience: the school was always headed in all directions at once as a matter of purpose, with few to no true unifying principles throughout its existence. A grand experiment in completely rethinking the structure of human life as we know it through art, there was a distinct vision at its inception. As Gropius put it [emphasis his] to "create a new guild of craftsmen, without the class distinctions which raise an arrogant barrier between craftsman and artist. Together let us conceive and create the new building of the future, which will embrace architecture and sculpture and painting in one unity and which will rise one day toward heaven from the hands of a million workers like the crystal symbol of a new faith." Though that may sound communist in nature (and indeed it did to the Nazis), the Bauhaus was officially staunchly apolitical.

In short, the Bauhaus eschewed all maxims beyond simply creating objects through a unity of artistic work across all fields. The various departments of the Bauhaus were segregated in name only, and cross-pollination was the written rule. As a consequence, the output could be prolific but unexpected. Though they did create several private houses and a couple of apartment blocks, along with a government building or two, the architects who ran the Bauhaus (Gropius was succeeded as director by Hannes Meyer and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, each serving a three-year stint) delivered far less built output before the school’s closure in 1933 than one might imagine. (Oddly, there was only an official architecture department for the last six years, and beyond their own facilities in Dessau perhaps the most notable architectural design to come out of the school was a losing bid for the Chicago Tribune Tower.)

Instead of hunching over drafting tables all day, architects busied themselves with interior design (Gropius crafted iconic door handles) and furniture (Marcel Breuer’s chairs); painters sculpted (László Moholy-Nagy was an early experimenter with Plexiglas) and metalworked (Marianne Brandt reinvented the idea of the lamp and the ashtray) and theorized (Wassily Kandinsky’s book Point and Line to Plane); printmakers created jewelry (Anni Albers) and light projection apparatuses (Ludwig Hirschfeld Mack).

Unlike the hit-and-miss results of many experimental and mixed-media artists, the Bauhaus masters and students produced valuable and groundbreaking works at a breakneck pace, so much so that their names have entered the modern lexicon in iconic form. A generation before Damien Hirst had Rachel Howard painting spots for him, and some 30 years before Robert Rauschenberg “erased” Willem De Kooning, Maholy-Nagy's "Telephone Pictures" were a genesis of conceptual art in 1922. Kandinsky is generally considered the progenitor of abstract expressionism. Naum Gabo’s name is synonymous with the origins of kinetic art. Moholy-Nagy and Paul Klee were working with spray paint in the 1920s. Johannes Itten and Josef Albers mixed speculative thought and demonstrative experimentation to lay the foundations for the contemporary principles of color theory. Kandinsky, Ludwig Hirschfeld Mack, Gertrud Grunow and Kurt Schwerdtfeger were all developing early experiments on the relationship between color and sound, unwittingly making their way into later scientific research on dissonance and synesthetic composition (a 1930 print of a "visual analysis of a piece of music, from a color-theory class with Wassily Kandinsky" by Heinrich Siegfried Bormann is included in the exhibit). Herbert Bayer pioneered the now-ubiquitous use of all lowercase letters and created typefaces that were a benchmark in graphic design.

Though it may have slept on the Bauhaus for the better part of a century, to its credit MoMA has recognized the diversity of the school’s output; and for “Bauhaus 1919–1933: Workshops for Modernity,” Bergdoll and Dickerman have augmented the museum's own collection of works with contributions from the Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin, Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau and Klassik Stiftung Weimar. The result is a thoroughly impressive catalogue of works. All told there are several hundred objects in the exhibition: a host of brochures, posters and sales catalogues and a collection of postcards from a dozen Bauhaus students and faculty; all manner of mixed-media collages; textile and wallpaper samples; photographs, paintings, woodcuts and illustrations; graphic design and typography sheets; architectural plans; furniture and housewares (from chairs and lamps to a baby cradle, teapots and inkwells); marionettes, toys and chess sets; 35mm film sequences; sculptural pieces made from glass, metal, plastic and even wooden aircraft propellers; and documentation of other projects that range from stained glass windows to promotion of an International Hygiene Exhibition.

There is scant work by Mies van der Rohe (two chairs, a page from a catalogue and the marked-up architectural drawings of a student), but virtually every other prominent Bauhaus artist is well covered, with several dozen works by Klee, Kandinsky and Moholy-Nagy alone. In addition to his letterpress and typography samples, Herbert Bayer's Thuringian banknotes and a series of 1924 designs for a newspaper stand, a cigarette pavilion, a movie theater and "an illuminated advertising sphere" are particularly interesting. Also of note is the juxtaposition between the two pieces from the lawyer, theater director and painter Lothar Schreyer: one is the 1920 design for a coffin ("death house for a woman") and the other the class schedule for the 1921–22 winter semester.

The development of the Bauhaus was eclectic in both concept and deed, and the sheer variety of works in “Workshops for Modernity” deftly illustrates that fact. While some of the aesthetic trends favored by many prominent Bauhaus artists were also present in other modernist movements, the Bauhaus was distinguished by the adaptation of technology and the utilitarianism of mass production. The school was also populated by German, Swiss, American, Russian, Dutch, Austrian, Hungarian, Slovenian, Ukrainian, Czechoslovakian and Japanese artists, most of whom were already then or would eventually become luminaries in architecture, painting, interior design, typography, sculpture, photography, weaving, printmaking, color theory and education. This diversity will be front and center in “Workshops for Modernity’s" Bauhaus Lab that accompanies the exhibition, an interactive program offering a series of symposiums, workshops and classroom experiments that focus on not only the mechanics of process employed at the school but also the cultural aspect of the Bauhaus, with selections highlighting the role of women and artists of various nationalities.

Though the Bauhaus itself was located in Germany, the school was short lived and afterwards the style lived on primarily in America. Oddly, if it weren't for the Nazis the development of modernism in the United States might have been at a much slower clip. After leaving Germany, sometimes with a stop in England or Switzerland, a good number of the school’s masters and students immigrated to the United States. Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer brought the newly reorganized Harvard Graduate School of Design to prominence in architecture; László Moholy-Nagy launched the New Bauhaus in Chicago, which quickly became the Illinois Institute of Technology's Institute of Design; Ludwig Hilberseimer and Mies van der Rohe also landed in Chicago with Maholy-Nagy, the latter of the two spawning a generation of eminent architects with his "God is in the details" approach; Anni and Josef Albers took over the painting program at Black Mountain College in North Carolina and instructed the likes of Cy Twombly, Robert Rauschenberg and Susan Weil; Herbert Bayer helped the Container Corporation of America (which developed the six-pack) revolutionize product packaging and advertising before moving on to Colorado's Aspen Institute; Werner Drewes was graphic arts director for the Works Progress Administration in New York and went on to teach painting and printmaking at the Brooklyn Museum, Columbia University and Washington University in St. Louis. The list of the Bauhaus' contributions to the art of American culture is virtually limitless. In the world at large, the Bauhaus footprint is simply astounding.

In terms of contemporary style and design, the Bauhaus reigns supreme as an overarching influence even today. The school's faculty, students and subsequent practitioners have directly resulted in everything from the tallest office building in Michigan (more than half a century before designing Comerica Tower at Detroit Center, architect Philip Johnson's career was inextricably altered after he met Mies) to the title script for the iconic TV show The Jeffersons (Herbert Bayer's "Universal" typeface is perhaps the most mimicked script in design history) to that lone red wall in your yuppie friend's apartment (scattered amongst the primarily black, white and gray faces of the Dessau campus were red walls and yellow ceilings) to virtually every aspect of popularized modern design.

Without the Bauhaus, who knows what the interior shots of the Sterling Cooper offices on Mad Men would look like: there would likely be no Mark Rothko paintings and the furniture would certainly be more Frank Lloyd Wright–style wood than Mies and Breuer’s metal. IKEA probably wouldn’t exist at all, and leafing through the latest issue of Dwell magazine feels like a tour through the Bauhaus catalogue. For their new exhibition MoMA has also constructed a Bauhaus Lounge that is "furnished with chairs, tables, and couches designed by Bauhaus faculty, and offers visitors a relaxing space to further explore the creative processes of Bauhaus artists."

“Bauhaus 1919–1933: Workshops for Modernity” runs until January 25. Additional information on the exhibition can be found at http://www.moma.org/bauhaus. European readers should note that there is currently a fantastic and extensive career retrospective of László Moholy-Nagy — one of the most astonishingly versatile, influential and progressive artists of the Bauhaus collective — running until the February 7 at the Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt, Germany.