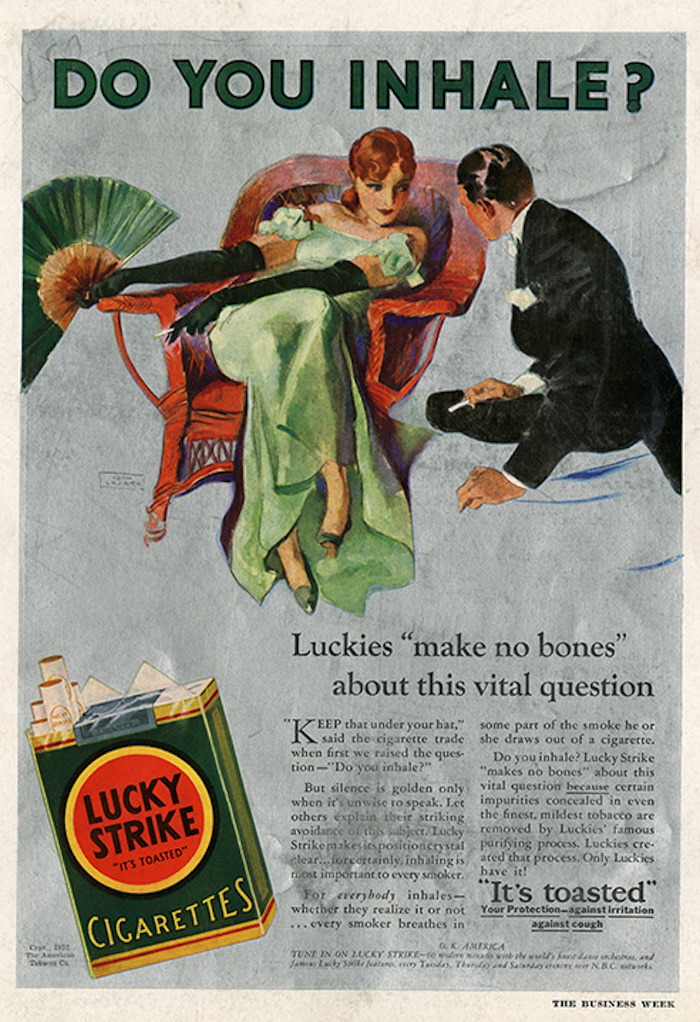

In the smoke and mirrors world of advertising of the early twentieth century, cigarettes ads seduced women into becoming habitual smokers. No expense was spared to push the myth that sophistication was just a puff away. A series of Lucky Strike magazine ads featured stylized paintings of women decked out in their evening finery. While the graphic design and typography was insignificant, the marriage of persuasive text and evocative image, presented in full color layouts and published in targeted women’s magazines was irresistible.

In “OK Miss America! We thank you for your patronage,” a woman wearing a revealing, low-cut satin gown is so above the fray that she isn’t even holding a Lucky, but the implication is that she had just finished a satisfying smoke. In the haughty “I do” advertisement a sultry bride pauses for a relaxed smoke and gives her vow to her cigarette of choice.

Cigarettes were marketed as fashion accessories, but these ads, which ran during the Great Depression, were not aimed exclusively to women of means—cigarette advertising promised an altogether better, stress-free, well-proportioned life.

One sales pitch used Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “First a Shadow Then a Sorrow,” to announce Lucky Strike’s diet plan. “Avoid that future shadow,” the copy suggested, “by refraining from over indulgence. If you would maintain the modern figure of fashion.” Under an idealized color painting of a young woman haunted by the shadow of a double chin, the copy read: “We do not represent that smoking Lucky Strike Cigarettes will bring modern figures or cause the reduction of flesh. We do declare that when tempted to do yourself too well, if you will ‘Reach for a Lucky’ instead, you will thus avoid over indulgence in things that cause excess weight and, by avoiding over indulgence maintain a modern, graceful form.”

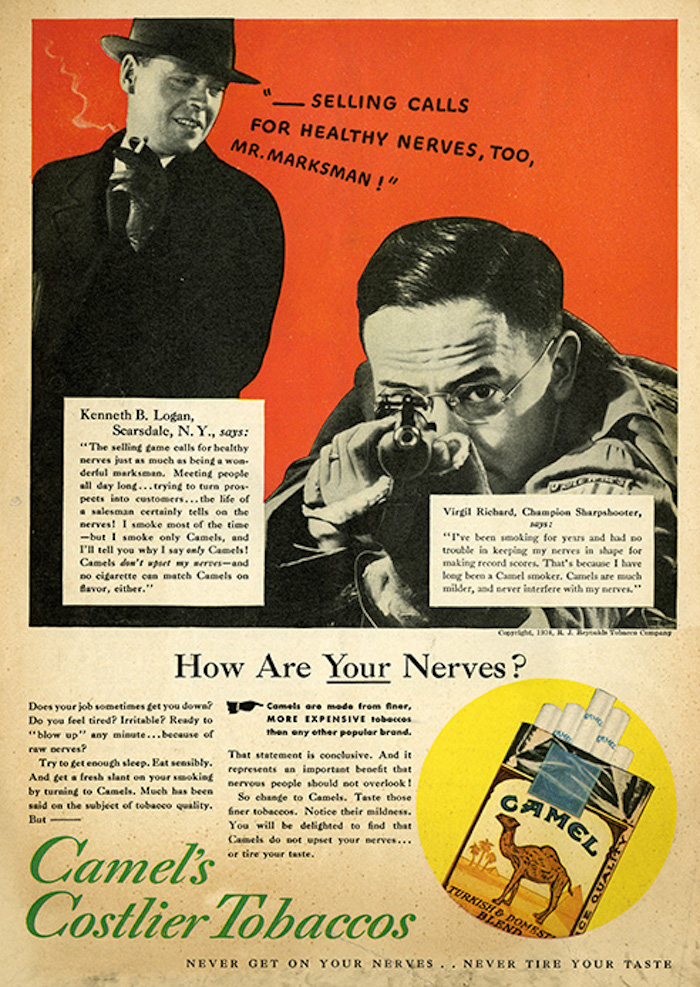

Cigarettes were a staple in America. Yet even tobacco manufacturers acknowledged frequent coughing, throat irritation, and raspy voices. The last was, however, promoted a virtue along with other benefits: “Smokers everywhere are turning to Camels for their delightful ‘energizing effect’ … Camels never get on your nerves …” Lucky Strike took the homeopathic route with their motto “It’s toasted.” A typical ad read: “Everyone knows that sunshine mellows—that’s why the ‘toasting’ process includes the use of Ultra Violet Rays … Everyone knows that heat purifies and so ‘toasting’—that extra secret process—removes harmful irritants that cause throat irritation and coughing.”

Movie stars and starlets frequently appeared as spokespersons. In a 1943 advertisement, Betty Grable, star of the movie Pinup Girl, is shown in a soldier’s barracks, reinforcing the idea that Chesterfield is overseas “With the boys …” To soldiers, cigarettes were as valuable as rations; to the tobacco industry the war was a boon. Ads invoked the image of American boys, exploited the image of American girls, and portrayed cigarettes as American as apple pie..

The cigarette ads created during the Great Depression and World War II were not beautifully designed or smartly composed but they effectively targeted women with one purpose: to seduce by appealing to their sense of fashion. While the stylistic manner of this seduction has changed since these ads were first printed, the method is still the same: appeal to weakness, bolster myth, and massage fantasy.