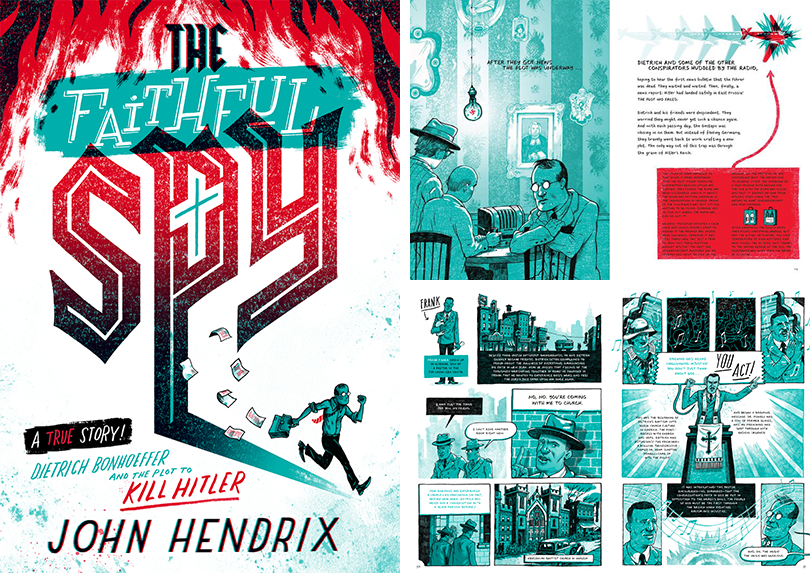

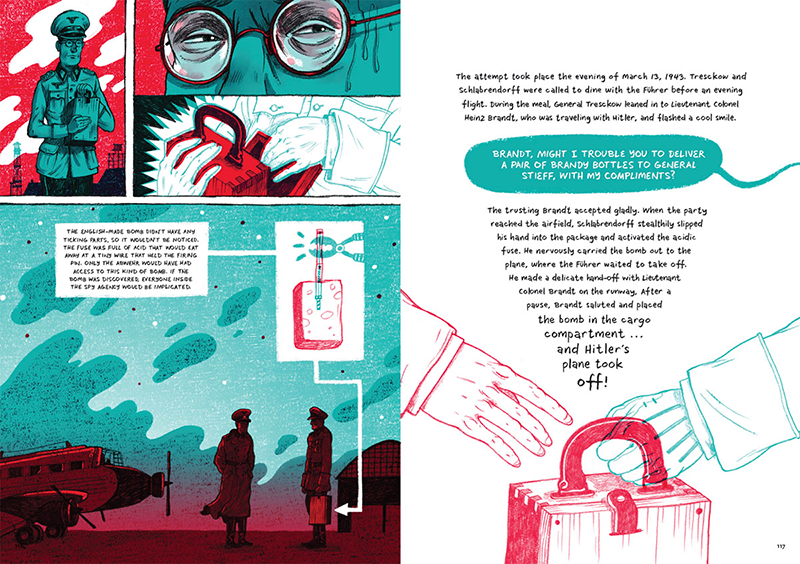

Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a German theologian and member of the Nazi resistance, vehemently fought the T4 euthanasia program and murderous persecution of the Jews. In April 1943 he was imprisoned. Linked to the July plot to assassinate Hitler, he was hanged in April 1945 just before the war’s end. His story is not exactly made for kids but author and illustrator John Hendrix has turned Bonhoeffer into a visual narrative for children ages from 10 years old onward titled “The Faithful Spy: A True Story, Dietrich Bonhoeffer and the Plot to Kill Hitler.”

Hendrix’s story is part history, part testament to conscience. I asked him why Bonhoeffer, a lesser known hero of the era, captured his interest.

He told me that he had read Dietrich's writing's in college. “Only later did I fully understand his story and role in the war,” he said. “It was one of those stories I was eager to tell for young people, but I couldn't figure out the right format. Most of my work with children's books was in picture book form and that didn't seem right for this story.”

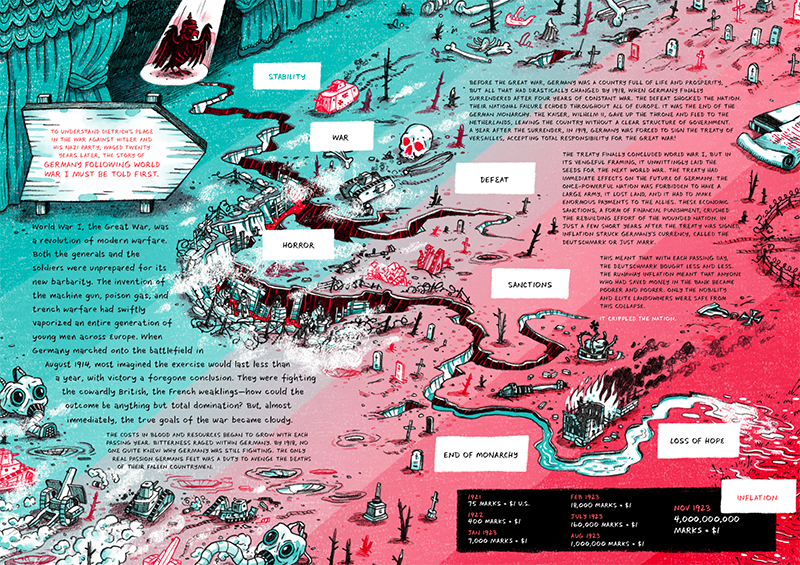

When constructing this story for middle grade readers ages 10-14, Hendrix needed to explain the context of Dietrich's world, so his moral choices would makes sense to them. This meant starting before the World War I to set the stage—“not the easiest of subjects to offer children in his age group.”

Hendrix’s and Bonhoeffer’s religious faith are quite similar. “Though I am not a Lutheran—I attend a Presbyterian Church—we cling to many of the most central pillars of orthodox Christianity,” Hendrix explains. “Dietrich was considered a 'conservative' theologian in the context of his peers in Germany at the time. But, to most of the American church today, Dietrich would probably been seen as more 'liberal.' His legacy in the church has always been a bit of a tug of war.”

During Bonhoeffer’s early years as a cleric, he spent a year in NYC where he attended the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, the legendary pulpit where Adam Clayton Powell Sr., among other African American religious orators preached. Hendrix believes that especially for a German, this time spent in New York had to have changed Bonhoeffer’s outlook on his world. “The African-American church connected two branches of his thinking at the time: His love for exuberant, heartfelt worship in corporate unity and his desire for the church to respond to the world around it.” Hendrix is not certain whether he ever met Powell Sr. in person, but he heard many of his sermons and saw the urgency that segregation, and the legacy that slavery and Jim Crow brought to the church. “This was new and something he didn't see in his church's at home in Germany,” Hendrix says.

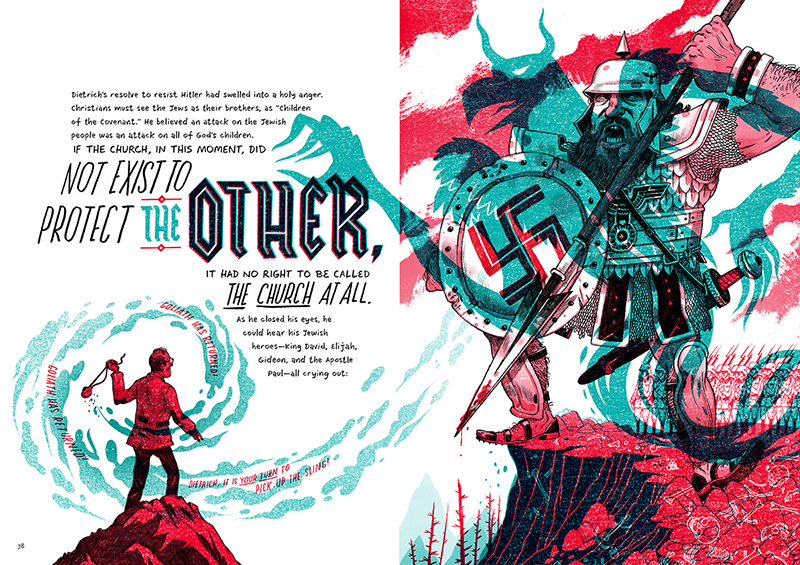

The parallels, though difficult to accept, between Hitler’s Germany and Jim Crow America motivated Hendrix’s embrace of this material. “There is no question that there are, sadly, direct connections to our current moment in the United States,” he acknowledges. “I started this book five years ago, and honestly wondered if we needed another book about the rise of Hitler. I have been horrified to see actual swastikas flying on our shores, and clearly we still need to tell young people the story of Nazi horrors.” Dietrich's connection to his own times has a lot do with lessons the American church can learn, Hendrix states, particularly the German's church willingness to accept Hitler transformation of the Christian church to the Nazi church, even down to raising the swastika to the height of religious icon.

“One of this aspects I really like about Dietrich's story is how he wrestled with the contradictions of his love of God and his love of country.” For young people today, he is a reminder that we don't fit easily into the boxes and labels that the world may assign us. His story is really about a costly kind of belief that requires sacrifice.

Bonhoeffer’s faith and conscience rises to the “saintliness” of Martin Luther King, Jr. Both are Christian Martyrs in that sense. Although Hendrix did not include this in the book, Bonhoeffer had correspondence with Ghandi, and had made plans to go to India to study with him, but ultimately stayed in the UK to continue the founding of his own church that he called the Confessing Church.

There is little record of Dietrich‘s inner life after his transfer out of Berlin in early 1945, prior to his execution. Hendrix believes he had hoped to escape (and nearly did). “I would guess that he would be astonished that so many know his story today. Ironically, it was his tragic death that propelled his legacy forward.”