Advertisement from The Learners: A Novel, design by Chip Kidd, 2008.

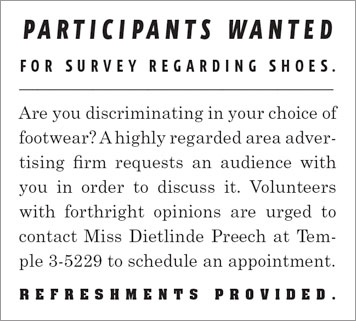

OUR STORY: It is the fall of 1961, in New Haven, Connecticut. Happy, the narrator of The Cheese Monkeys, has graduated from State with a Bachelor of Art’s degree (emphasis in Graphic Design) and has sought and found employment as a deputy lay-out artist at the small advertising agency of Spear, Rakoff and Ware. At this point in the book the firm is desperately trying to win the account for Buckle Shoes, a large footwear manufacturer that has just moved into town. And so, Happy and his colleague — the junior copywriter Tip Skikne — have placed an advertisement in the local paper to solicit opinions from prospective customers to help inform their pitch. Above is the ad as it ran.

Chip Kidd's new novel, The Learners: A Novel, according to Newsweek, "exploits the ironic parallels between our time and another era where new technology and restless twenty-somethings were looking forward not back." Courtesy of the author, Design Observer is pleased to present an excerpt from this novel. [And don't miss the video.]

The Learners: An excerpt from the novel by Chip Kidd

“So what are the refreshments?” I didn’t see any on Tip’s desk.

“Very, very special,” he said, dragging a spare office chair behind the card table he’d set up next to the window. “I have a flyswatter that’s been dipped in tar and gravel. After the interview I’ll give them a quick smack across the face with it. Who wouldn’t be refreshed by that?” Just then his intercom squelched to life. Miss Preech: “Your five o’clock is here. The respondent to the shoe ad. A Mr. Harshbarger.”

“Send him up.” Tip rubbed his hands listlessly. “Oh, I’m just filled with antisappointment.”

“Pardon?”

“Antisappointment. Anticipation colliding head-on with the certainty of its own doom.”

“Oh, don’t be so pessimistic.” I wished I meant it. “Can I stay?”

“Please do. I’ll need a witness.”

“Ahem.” Outside the doorway, Miss Preech’s head bobbed up behind a large, ungainly fellow in a porkpie hat, red-and-black plaid hunting jacket, and wide-wale caramel duck-patterned corduroys. Wisps of red hair peeked out behind each ear, and freckles dotted his alabaster cheeks, crimson-ringed by the crisp fall day.

“Marvin Harshbarger,” he bellowed amiably, removing his hat and thrusting out a hand the size of a bear trap.

Which was how Tip regarded it. “Pleasure.”

“Is this where I get the free shoes?”

Tip gleamed, with mild alarm. “I’m afraid that’s not in the offing, sir. You are here for the ad?”

“Oh, yes,” he said, with confidence, “but I thought I’d get shoes.”

“My dear fellow. What you will get will be far more valuable than a mere pair of dogsleds.”

He held his hat to his barrel chest and looked a little sad. “Like what?”

“Knowledge! The sustaining certainty that you have helped your fellow man, so selflessly.”

“Hmm.”

“What we are interested in, my colleague and I,” he nodded to me, “is to engage you, as a valuable potential customer, in a dialogue. We’d like to get your thoughts on shoes, in an effort to inform the direction of a current related project here. Okay? Do have a seat, please. Make yourself comfortable.”

“Okay, I guess.” Marvin Harshbarger released his sizable frame from the confines of the bulky woolen coat and draped it on the chair, which swallowed it whole. Then he planted himself with a grunt.

Tip snatched the pencil from behind his ear. “All right, sir. First, we’re just going to do some simple word association. I’m going to dictate a series of words, then with each one, you just say whatever word pops into your head. Okay?”

“Does my word have to be about shoes?”

“No, of course not. It can be about anything. Whatever pops into your head.”

“Gotcha.”

Tip sat on the edge of his desk, legal pad in hand. “Ready?”

“Shoot.”

“Comfort.”

“Apples.”

“Hmm,” Tip jotted it down. “Feet.”

“Apples.”

“Durability.”

“Apples.”

“Style.”

A pause. “Apples.”

“Flexible.”

“App—”

“Mr. Harshbarger,” Tip cut in.

“Apples. Oh—Marvin, please.”

“Marvin,” he said, with gentle authority, “when I told you to say a word, I didn’t mean it had to be the same one, every time.”

“Oooohhhh. I git’ya. Right.” He flushed a bit. He was kind of sweet, actually, in a Baby Huey sort of way.

“So let’s try it again, yes?”

“Sure.”

“Okay.” A breath. “Arches.”

“App—oops! Uh, artichokes.”

“Laces.”

“Lemons.”

“Value.”

“Vegetables.”

“Soles.”

“Sprouts.”

“Heel.”

“Horseradish.”

“Loafer.”

“Lettuce.”

“Buckle.”

“Beets.”

One could see where this was going. “Mr. — I mean, Marvin, if I may ask, what is your profession?”

“I own a produce business. Twelve years now.”

“Aha. Wonderful.” He shut his eyes in thought. “Now let’s try something else.”

“Yessir.”

“Tell me, when you’re selecting a new pair of shoes, either in a store, or from a catalogue or an advertisement, what is it you look for most?”

“Steel toes.”

“Ah-hah.” Tip waited for more.

And waited. “That’s it?”

“Yup. You ever drop a fifty-pound crate of muskmelons on yer foot?”

“I can’t say I have.”

“Well, try it sometime.” With no warning, Marvin Harshbarger hiked up and extended his left leg and let it slam onto the table with a deadening clunk. He scrunched in the cuff of the corduroys to fully expose his shin-high tan leather rubber-soled work boot, laced tightly with black suede cord all the way to the tip of the tongue and festooned with a network of brass-fitted eyelets. From the size of it, it could have been one of Paul Bunyan’s. “LOOK at that craftsmanship.” His eyes shown with new, unwelcome enthusiasm. “Isn’t that something?”

Tip pretended to take notes. “It, it certainly is.”

“John Deere. Best tractor boot money can buy. Wanna see how much this sucker can take?”

“Oh, that won’t be necess—”

“Hah!” Marvin’s hand darted into his coat and removed . . . “Watch this.” . . . a small .22-calibre hunting pistol. He aimed it squarely at his left foot.

“NO!!” Tip erupted. “Mr. Harshbarger!!”

I instinctively dropped my notebook and ducked behind the filing cabinet.

“It’s okay, it’s okay,” Marvin said matter-of-factly, “I got a license for it.”

“THAT’S.” Tip cowered and held out his hand, as if staving off a beating, “That’s not the issue.” Gulping for air. “PLEASE put the, put it away. Please.”

Harshbarger rolled his eyes and pocketed the gun. “Okay.” He dropped his massive leg to the floor. “Now what?”

“Well, I think,” Tip looked at his watch and wiped his forehead with a handkerchief, the cloth fluttering as he shook, “I think that about covers it, actually. Thanks.”

“Really? Already?”

“Oh, yes. We’ve accomplished so, so much. I can’t really think of anything else.” He glared at me, with post-traumatic relief. “Can you?”

All I could do was shake my head.

“Right. So.” Tip made like he was tallying up the data on his legal pad. “We have a very busy schedule, as I’m sure do you, Mr. Harshbarger. My sincerest thanks, you’ve been OH so helpful. You are a gentleman and a scholar.”

“Much obliged.” Marvin stood, pulled on his coat and hat, and began to lumber out. Something stopped him. “It said there’d be refreshments.”

I pictured the flyswatter, swiped swift and sharp across Marvin’s ample cheeks. Then, Tip and I facedown on the floor. Bleeding to death.

“Oh, yes,” replied Tip, his calm restored. “You have your choice: Kools or Lucky Strikes.”

“I don’t smoke.”

“Kools, then? They’re filtered.”

He took the Kools.

If anything, it was downhill from there. The following two days’ worth of respondees consisted of: a toothless septuagenarian who smelled like an old bar rag and communicated exclusively with clicks of his tongue, high-pitched wheezes, and spasmodic sign language of his own invention; an out-of-work commercial truck driver from Mississippi named Ferd who responded to the ad because it had the word “discriminating” in it and declared, “I totally agree with y’all that it’s all the nee-grows’ fault” while manicuring himself with a rusty switchblade; and Ursula — a forty-three-year-old self-described ex-semi-professional wrestler-housewife and mother of four cats, who, when faced with the word association game instantly and without the slightest provocation burst into tears and sobbed uncontrollably, full-on, for five minutes.

All of them were under the impression that they would be shod and fed, and not one provided even a shred of insight of any use whatsoever — with the possible exception of Ursula, who, when she finally stopped crying, took a deep breath and mightily sighed, “Whew, I needed that!”

She wasn’t antisappointed at all.

“Gee, what a rousing success.” It was Sunday afternoon and Tip had just closed the front door behind Ursula, bolting the lock. “So let’s review what we’ve learned. Buckle shoes should be:” He counted off consecutive fingers of his right hand, “Bullet proof, deodorizing, racially superior, and super-salineabsorbent. Christ.” He slumped on the couch and stared into space.

“It was a good idea, really,” I weakly tried to assure him, wondering if Dr. Milgram got his share of kooks, too. Probably yes then no — he had assistants at the university to weed them out.

But we didn’t have that luxury, and Tip saw no point in going on with the interviews, wasting more money and time. “At this rate, we’d get the three blind mice,” he muttered, “squeaking at us that their favorite color is gorganzola.”