Atomic test at Bikini Atoll, 1955

Remember the scene in Woody Allen’s Annie Hall in Dr. Flicker’s examining room where Alvy Singer’s angst-ridden mother tells the doctor her son is depressed? As the doctor furiously puffs on a cigarette, Alvy says the universe is expanding and since “the universe is everything, and if it's expanding, someday it will break apart and that would be the end of everything!”

“What is that your business? What has the universe got to do with it?,” screams Alvy’s mother. “You're here in Brooklyn! Brooklyn is not expanding!” To which Dr. Flicker adds, “It won't be expanding for billions of years yet, Alvy. And we've gotta try to enjoy ourselves while we're here. Uh?”

Existential gloom and doom scenarios have not just plagued the sackcloth and ash crowd. Many of the most rational among us have been consumed by the specter of endgame.

"City Aflame: The Real Day After Tomorrow," artwork by Virgil Findlay, c. 1930

Of course, the world’s great religions have built their respective brand stories on one or another version of Armageddon. But even for those without religious underpinnings the apocalypse is nothing to be sniffed at. If it is not a shower of killer asteroids falling from the heavens then it is a barrage of atomic warhead missiles shot from submarines. H.G. Wells’ prescient The Time Machine first published in 1895 accurately predicted two twentieth century world wars, and prophesized a third that promised to send planet earth back to the Stone Age; and he had absolutely no inkling of nuclear weaponry at the time.

He was not the first (or the last). The seer Nostradamus (1503-1566) was famously known for his book Les Propheties, which to this day triggers considerable trepidation among those who read too much into his metaphors.

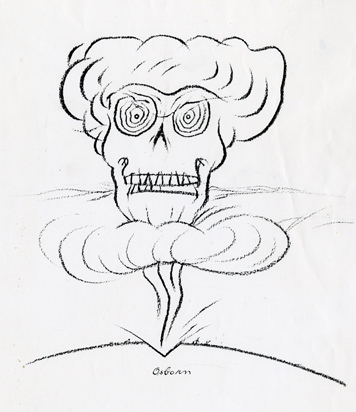

"Atomic face," artwork by Robert Osborn from War is No Damn Good, 1946

Conjecture about earth-shattering calamities — manmade or not — is a recurring trope of artists and writers. Predicting the unthinkable is a kind of sport for the practitioners of what’s called “counterfactual history.” Fans of the genre seem to savor the sublime morbidity in the same way we relish extremely spicy food, it takes a little getting used to but the ultimate kick (in this case, the pleasure of fear) is worth the discomfort.

I’ve often considered starting a cable channel exclusively devoted to fiction and faction about the world’s end — Endgame TV. While it would not be for the feint of heart, it would have a real voyeuristic following. Maybe, like the old joke about the guy not minding being hit over the head with a hammer because it felt so good when it stopped hurting, once we awake from these “nightmares” we feel so much better, or do we?

In the early Sixties, during the zenith of the atomic scare, Rod Serling’s Twilight Zone was demise central. Scores of episodes focused on how humans sent the planet earth on a one-way ticket to Palookaville. You may remember the episode “The Midnight Sun” (1961) in which the Earth suddenly changed its elliptical orbit and in doing so began to follow a path that gradually took it closer to the sun. The place was New York City and it was the eve of the end, because even at midnight it was high noon, the hottest day in history. Towards the end of the episode Lois Nettleton, who played the terrified protagonist, awakened from what had been a nightmare. In her Twilight Zone reawakening the world is dark, cold and snowing. Whew! However, rather than being saved from extinction, the audience learns that a new orbit is really leading the earth father and farther away from the sun into frozen oblivion. Our protagonist had gone from one nightmare state into another.

Movie poster of The Night the World Exploded!, 1957

Through films and books, hundreds, maybe thousands of endgame scenarios have been played out. Movies like the early sixties classic The Day the Earth Caught Fire was but one of the many Cold War cautionary tales that portrayed the planet as a powder keg set to explode. The Bomb (as it was quaintly known) had become the greatest portend of doom and the mushroom cloud was the most horrifyingly dread symbol imaginable. In the sixties fallout shelter kits were being advertised and yellow and black shelter signs were ubiquitous. After seeing the Twilight Zone episode, “The Shelter,” I begged my parents to build one — now that’s successful product placement.

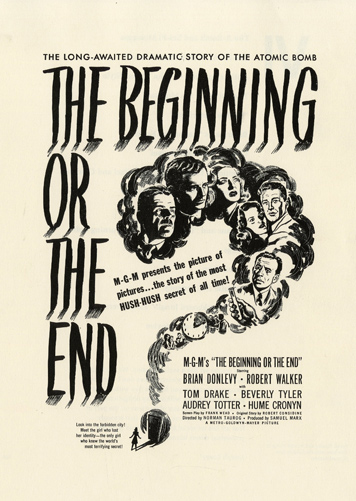

I kind of miss those halcyon days of Cold War fear, when, to borrow FDR’s famous phrase, "all we had to fear was fear itself" — and atomic annihilation. As harrowing as the movies and books on the subject were, there was often a level of absurdity that took the edge off reality. The shocking story of nuclear uncertainty in the film The Beginning or the End, was given such a Hollywood aura of unreality that the a-bomb was transformed into our friend. While films like Fail Safe (1964) and On the Beach (1959) were tragic tales, we knew once the film was over our lives would return to normal. The unthinkable just wouldn’t or couldn’t happen. Then, of course, there was the ludicrousness of Dr. Strangelove (1964) (years before we heard of Henry Kissinger), which although savagely sardonic made it clear our leaders weren’t THAT crazy. By the time Mad Max (1979) came along, the endgame had turned into fashion that looked suspiciously like the clothes Vivian Westwood was making for the Punk scene.

Movie poster of The Beginning or the End, 1947

Recently, the world has become a more dangerous place in the movies and literature. The bomb is not the only thing to fear: global warming, killer viruses, and natural and unnatural plagues of every description are only a few of the uglies now feeding apocalypse paranoia. Films like Waterworld (1995), The Day After Tomorrow (2004), and most recently I Am Legend (2007) address the real concerns of our altering planetary conditions and continue to titillate our prurient interest in doom. But now they seem much more likely than ever before. Where once the sky is falling scenarios would not, as Dr. Flicker said, “happen for billions of years yet,” the doomsday clock is steadily ticking away. Wouldn’t it be nice if we could go back to the days when fiction was not fact.