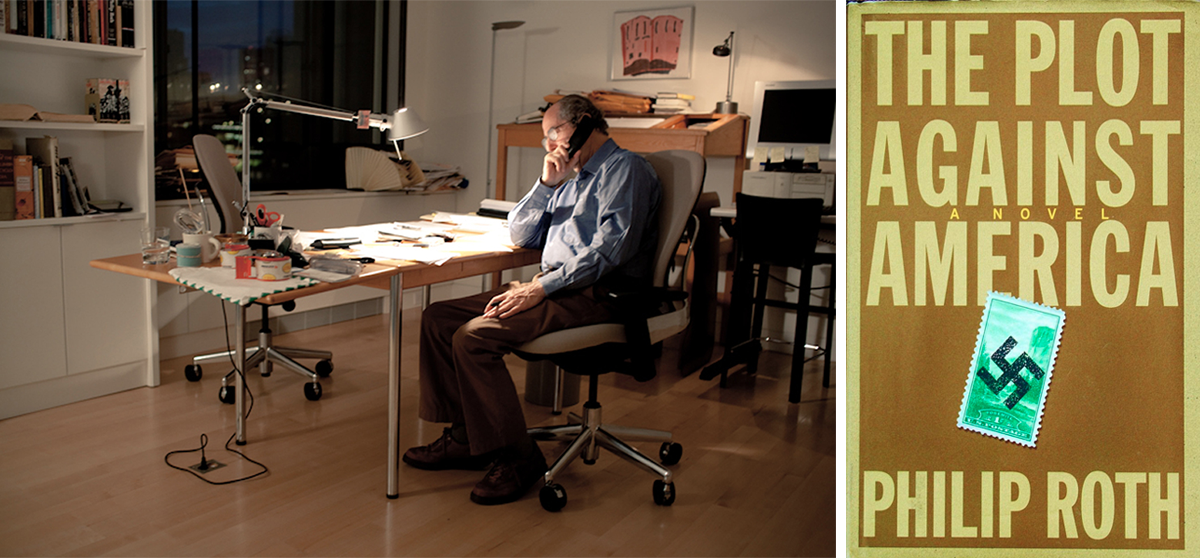

(Left) Philip Roth in his Manhattan apartment during filming for American Masters Philip Roth: Unmasked. Photo Credit: ©François Reumont (Right) Book cover.

The 2016 election. The most surreal political event in my lifetime. I followed the action from Twitter, hashtag by absurd hashtag, until things got so crazy that I had to slap my laptop shut. Often recalling a line from Leon Wieseltier—“I don’t know what to do. No, I know what to do. I will open a book.”—I’d walk over to my shelves and extract a volume. One day, I pulled down Philip Roth’s 2004 novel, The Plot Against America.

The Plot is a counter-historical novel centered on a seven-year-old Philip Roth growing up in a world where Charles Lindberg, celebrity-aviator, isolationist, and anti-Semite, wins the Presidency of the United States with a certain populist message: “America First.” This causes huge amounts of havoc for the Roths, and many others.

But buried in The Plot is a surprise. I didn’t realize until this go-around, but the novel contains, among many other virtues, a superb illustration of how empathy informs good design. That’s right: Philip Roth, designer manqué!

It’s not surprising that an acute novelist such as Roth would understand design. Just flip back to The Ghost Writer (1979) and recall the passage in which his protagonist, 23-year-old Nathan Zuckerman, is invited to the house of the eminent writer I. L. Lonoff:

The living room he took me into was neat, cozy, and plain: a large circular rug, some slipcovered easy chairs, a worn sofa, a long wall of books, a piano, a phonograph, an oak library table systematically stacked with journals and magazines. Above the white wainscoting, the pale-yellow walls were bare but for half a dozen amateur watercolors of the old farmhouse in different seasons. Beyond the cushioned windowseats and the colorless cotton curtains tied primly back I could see the bare limbs of big dark maple trees and fields of driven snow. Purity. Serenity. Simplicity. Seclusion. All one’s concentration and flamboyance and originality reserved for the grueling, exalted, transcendent calling. I looked around and I thought, “This is how I will live.”

A novelist describing a room is, in fact, a kind of designer. You see in this passage Roth’s understanding how each element of Lonoff’s living quarters—homey, appropriately aged New England furniture placed among various tools and vessels of culture—resonates with the others to produce an intended emotional response. (The literature buffs among you might now remember T.S. Eliot’s idea of the objective correlative.) It’s clearly a space intended for the production of serious literature! Phrases such as “colorless cotton curtains tied primly back” and the subtly judgmental “amateur watercolors,” reveal Roth’s meticulousness and suggests someone who would create an extremely intentional living space of his own. And his protagonist’s response to the room, a litany of sonorous single words, follows the minimalist Lonovian décor: “Purity. Serenity. Simplicity. Seclusion.” (In a later volume in the Zuckerman series, an older Nathan’s apartment is described as resembling “the pad of a well-heeled monk.”) The bit about the transcendent calling might have been cribbed from Flaubert: “Be regular and orderly in your life like a bourgeois, so that you may be violent and original in your work.” But you forgive young Nathan from borrowing; he was just a kid.

Back to The Plot. Little Philip Roth, the fictional version of the author’s single-digit self, engages in his act of design on page 145 of the novel. This surge of empathy takes place after Philip is traumatized by the reality of having to share a room with his war veteran cousin, Alvin, whose leg was blown off in combat. At first horrified by his roommate’s scabrous stump, Philip soon becomes Alvin’s caretaker. “Wherever I was and no matter what I was supposed to be doing, I found myself thinking about Alvin and how I could help him forget about his prosthesis.”

This stump-obsession eventually calls an idea to Philip. He says to his mom: “If Alvin had a zipper on the side of his pant leg, it would be easier for him, wouldn’t it, to get in and out of his pants when he’s got his leg on?”

Doesn’t this sound like a line from a brainstorming session? You can easily imagine a designer jumping up to the whiteboard to sketch out a pair of pants and carefully drawing in a side zipper, complete with markered teeth.

The next day, Philip’s mother then takes Alvin’s army pants to a local seamstress, “who was able to open up the side seam and sew in a zipper that extended some six inches up the uncuffed pant leg.” The result of this innovation? Later on, “when Alvin pulled on the trousers after having undone the zipper, the pant leg passed easily up the prosthesis without his having to curse everyone on earth just because he was getting dressed.”

Success!

The unhappy, self-pitying Alvin is suddenly extremely grateful for Philip, saying: “I couldn’t live without you” and “I couldn’t put my pants on without you,” giving the kid-designer “to keep forever” the medal he’d won from the Canadian government for fighting Nazis.

The thing that’s so wonderful about the design element of The Plot is that Roth, whose work is allergic to didacticism, surely wasn’t trying to parallel park it into the text. There is, therefore, no strain in the telling; it fits naturally into the narrative. Which is why, if I were teaching an introductory design class, I’d put it on the syllabus.

It’s also worth noting that the empathy illustrated here is familial. In many design contexts, empathy has a decidedly economic end. But the empathy of the novel’s kid-hero demonstrates that the desire to use design to improve the lot of another human can, and perhaps should, have a personal origin. We need to, and can, cultivate the humanistic element of design at home, amongst the people we live with and love, and I think this story could well prompt others—general readers and design students alike.

There is, of course, much more to The Plot, to Alvin (who isn’t much of a hero), and to young Philip Roth and the rest of the characters. The Plot is a novel of grand design, and I’d love to see more designers read this, and other such books, as a way of educating themselves in empathy. Submersing ourselves in great works of literature is a wonderful way to train us to be more human.

So I say to you, designers, students, aspiring humanists: If you’re serious about understanding people, feeling for people, and using that to inform your design, you’d do well to read superlative works of fiction. The Plot is a fantastic example, but it’s one of many, many volumes you should be extracting from the shelves. Have you got a favorite example? Let’s hear it in the comments below.