Some five centuries after Sir Thomas More, is utopia is still something which can be usefully imagined in print? With the publication of The Feminist Utopia Project: Fifty-Seven Visions of a Wildly Better Future, editors Alexandra Brodsky and Rachel Kauder Nalebuff answer with an energetic affirmative. Following More’s example of using the ideal as a critique of the real, the contributors to the book offer a wide variety of written and visual dreams of a feminist future. Brodsky and Kalebuff cannily use their publication to explore the hierarchies of conventional print form while anthologizing the highlights of social media conversations, text exchanges and digitally transmitted oral exchanges. The result is a volume which is at once a heterogeneous sampling of contemporary feminism as well as a productive inquiry into the contemporary relationship between print and digital media. Publication by CUNY’s Feminist Press was a validating step in a larger project, adding levity and expanding audiences, but it is in no sense the end of the project, the editors remind the readers in the their introduction. Following the book’s publication, the Feminist Utopia Project migrated back online, where readers can post their own visions of utopia. This is a book intended to be read with smartphone in hand.

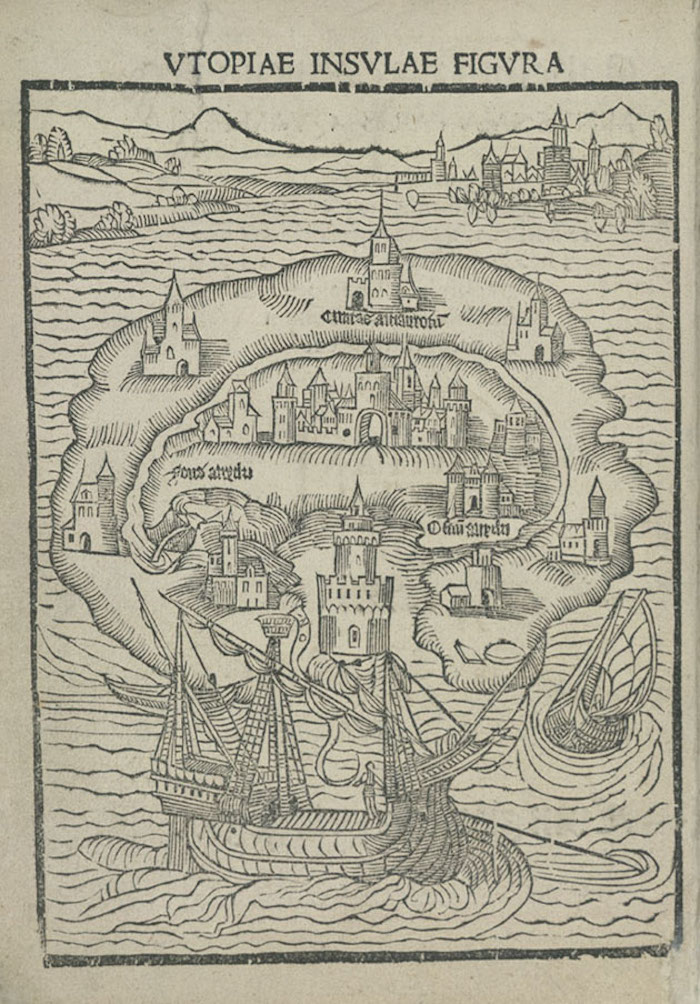

Thomas More, Utopia (1516); © The British Library Board

Thomas More, Utopia (1516); © The British Library Board

Thomas More, Utopia (1516); © The British Library Board

Thomas More, Utopia (1516); © The British Library BoardIn mission and design, The Feminist Utopia Project foregrounds equality and transparency. Readers must navigate an explanation of the process, compensation and design objectives of the book project before lifting an extended front flap to reach a circular table of contents. (More’s Utopia was a rounded island of fifty-four cities; the feminist version is apparently a rounded list of fifty-seven contributors). The contributions are defiantly not grouped into thematic categories; the guiding idea behind this presentation is that it should encourage readers to read according to whim or interest, rather than following the dominating vision of an editor. There are many passionate and curious visions in the anthology: the adult performer Sovereign Syre provocatively discusses the systematic undervaluing of “emotional labor” in contemporary culture—a category which she defines to include the work of nurses, flight attendants, and porn stars. Playwright Abigail Carney imagines the calm of a world where “most people do not notice” when gendered pronouns simply drop out of Biblical text. Sheila Heti productively interviews the Canadian feminist Judy Rebick of rabble.ca. The most useful comments are made by Melissa Harris-Perry, who stresses the value of utopia as an ongoing interrogation, rather than a closed set of ideas or a finished state. Despite the editors’ best efforts to eliminate any authorial hierarchy, those who express themselves for a living are at a clear advantage here. Taken together, many of the contributor’s visions are sadly mundane: the themes of universal access to high quality childcare, equitable health care, and a built environment which is navigable for all the earth’s citizens recur again and again. Whatever a feminist utopia might be, it’s clear that in 2015, it’s not a very sensual place, nor a very funny one.

The visual elements of The Feminist Utopia Project succeed to varying degrees—perhaps as one might expect from any utopian endeavor. There are relatively few contributions by visual artists; Yumi Sakugawa’s comic “Seven Rituals from the Feminist Utopia” perhaps best survives translation to the small format of the paperback edition. Working in collaboration with Nalebuff and Brodsky, designers Drew Stevens and Suki Boynton replaced the traditional index with a list of “Imperfect Categories”; the result is interesting but difficult to use. The fonts used in the book (Zusana Licko’s Filosofia and Claudia Kipp’s Expansion) are labeled as feminist, but it is not clear how this is the case. Boynton designed a dozen mysterious icons for the cover: some, such as a shovel, scale and hatchet, are indicative of energy or equality, but the true meaning remains hidden. Perhaps this was deliberate: the inhabitants of More’s Utopia also had their own private runes, unintelligible to outsiders. The most fanciful visual intervention is the placement of one of Boynton’s rocket icons in the right-hand margin of the book’s pages. When the pages are riffled at speed, a flip-book illusion is created and the rocket takes off from the bottom of the page. The upward energy of the effect is a lovely metaphor and a clever exploitation of a forgotten animation principle. However, the illusion only works if the reader bucks the editors’ instructions and read the book conventionally, moving in a non-utopian progression from front to back.