This post is the first in an occasional series. The idea is to revisit a book from my bookshelf. Some will be books I use often. Some might have been gathering dust. Sometimes they’ll be about visual subjects, sometimes they’ll be visually notable and sometimes they’ll be both. It could be a publication of intense relevance to me, it could have obvious wider significance, or it could work both ways.

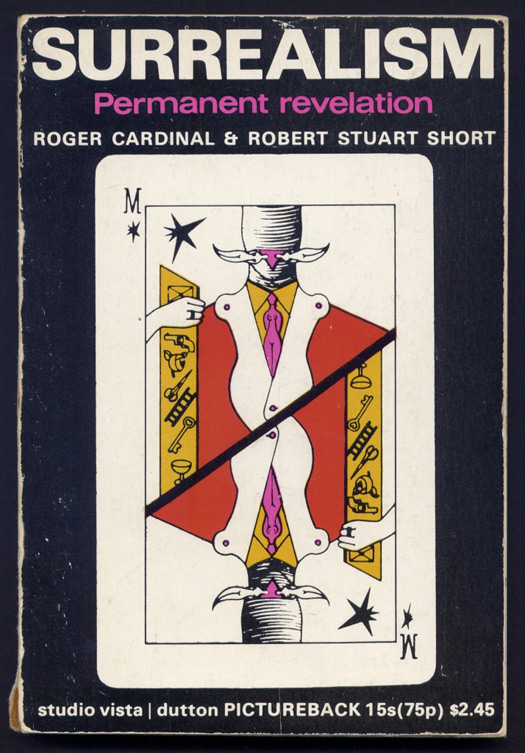

I want to start with a volume that hit me like a runaway truck full of madmen when I bought it in my teens. I have mentioned it in recent months in a lecture I have been giving about Surrealism and graphic design and I touched on it in a column for Print. The book is Surrealism: Permanent Revelation by Roger Cardinal and Robert Stuart Short and it was published in London in 1970 in the Studio Vista/Dutton Pictureback series. This was a collection of brilliantly conceived and rather wonderful small-format, inexpensive paperbacks dealing with everything from African sculpture and Art Nouveau to movie monsters and cybernetics.

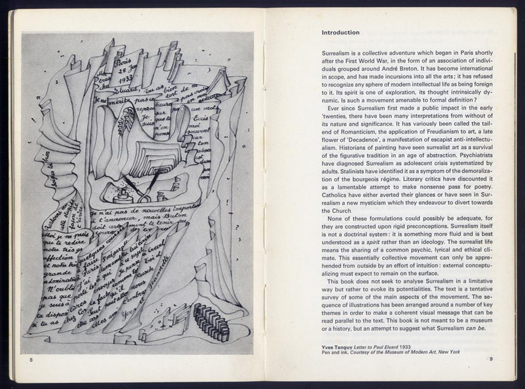

Since discovering Permanent Revelation, I have read many books about Surrealism. I still think it’s one of the best and I still return to it. It doesn’t merely summarize the Surrealist sensibility; written in the late 1960s, during a period of counter-cultural uproar, a text that might have offered only a perfunctory account of a bygone art movement shows every sign of sharing the Surrealists’ belief in the urgent necessity for life-transforming poetic revolution. The authors were scholars and academics: Cardinal went on to a distinguished career as a professor of literary and visual studies. Nevertheless, they write not as dried-out documentarians, but as impassioned bearers of the message. Here’s just one of the passages I underlined in pencil, in a fever of teenage revelation, all those years ago:

Surrealism posits an integral philosophy of freedom. The full autonomy of desire is its implicit goal, one which is never lost from view. Since desire makes itself known whenever it is allowed to express itself in freedom, Surrealism has never ceased to seek the means to achieve such freedom. The surrealist interest in love, in the mechanisms that make people find certain objects appealing, in the function of language in our absent-minded moments; the practice of automatic writing and spontaneous painting; the passion for the manifestations of lunacy […] all these interests relate to the central motive of Surrealism — the recuperation of man’s lost powers. (p. 35 in a chapter titled “The Surrealist Proposition”)

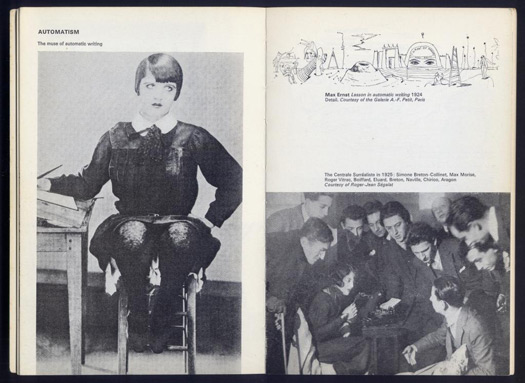

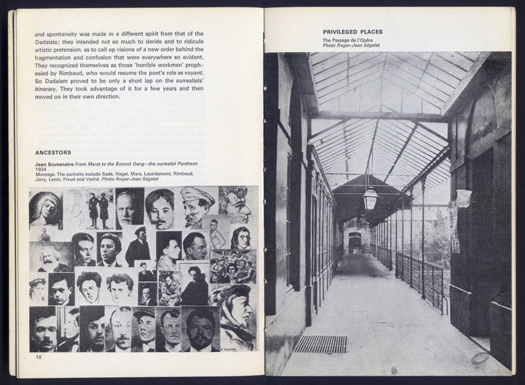

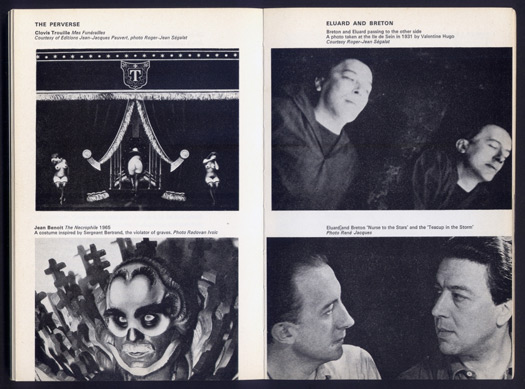

The other aspect of the book that impressed me back then was the organization of the pictures: I studied the images and their visual relationships on the page as avidly as I did the text. Even now, this seems to me exceptionally well done, once again suggesting just how close the authors were to their subject. The picture headings — Privileged Places, Automatism, Dream and Nightmare, Eyes, Mannequins, Convulsive Beauty, The Perverse, Revolutionary Action — offer a telegraphically compressed synopsis of Surrealism’s most potent and enduring themes.

As a guide to what the movement stood for, the book is still a provocative place to start. It’s not easy to find now, but desire is a magnet — see “objective chance.”