Austerlitz, Penguin Books, 2002

W.G. Sebald, who died in a car crash in 2001, is one of the greatest European writers of recent years. His books Vertigo (1990), The Emigrants (1993), The Rings of Saturn (1995) and Austerlitz (2001), all first published in German, defy easy categorization. They have been summarized as part hybrid fiction, part memoir and part travelogue, while the adjectives most frequently used to describe their extraordinary prose style, built on long, elegant sentences, are “haunting” and “mesmeric.” These four books affected me more deeply than anything I have read in a long time. I share the view of many Sebald readers that Austerlitz is a masterwork, a book so good that you find yourself constantly rereading passages to savor the luminous intensity with which he evokes people encountered, places visited, things seen and atmospheres recalled.

Sebald is brilliantly visual. He makes you realize with some discomfort that you often fail to look attentively enough at what you see. Another novelist referred to the “phenomenal configuration” of the author’s mind and what astonishes and delights in Sebald’s sentences, superbly rendered by his translators, is his ability to convey not just the detail of so many things hitting the senses in a rain of fleeting simultaneous impressions, but the precise emotional shading and personal import of each of these moments. His eye records with photographic accuracy and then these perceptions are recovered from memory and reconstituted as fictional experience with the same exhilaratingly scrupulous fidelity. The complication in Sebald’s writing, which he apparently intended, lies in our uncertainty about how much of what he describes derives from his own experiences (seemingly a lot) and how much of it is largely or entirely imagined. Based on a reading of the books alone, the narrators show every sign of being Sebald himself, but we know from what he has said elsewhere that these melancholy figures are fictionalized versions of the author.

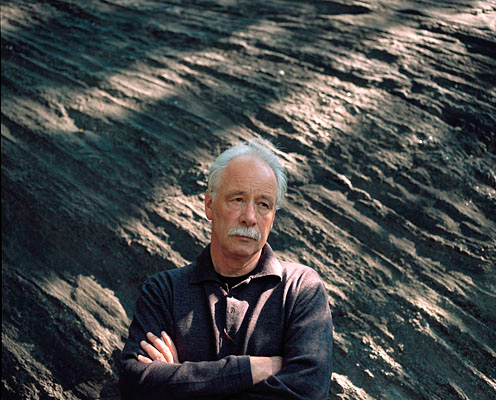

W.G. Sebald

Another striking aspect of the books is the use Sebald makes of photographs and other visual material, such as architectural plans, engravings, paintings and restaurant bills. He drops these uncaptioned images into the text, providing an additional level of documentary “evidence,” and you become convinced that Sebald really must have undertaken the walk or visited the building that his narrator describes. Literary reviewers usually note the presence of these images, acknowledging that they add to the books’ unique flavor, but their role in the composition of the texts and the exact ways in which text and images relate to each other have received little attention. This is not something that reviewers usually have to consider since few literary writers work with embedded photographs and images. John Berger, beginning with A Fortunate Man (1967), using photographs by his friend Jean Mohr, is one of the most notable. Geoff Dyer’s The Missing of the Somme (1994), a book about war and remembrance, also Sebald’s themes, has elements of this approach.

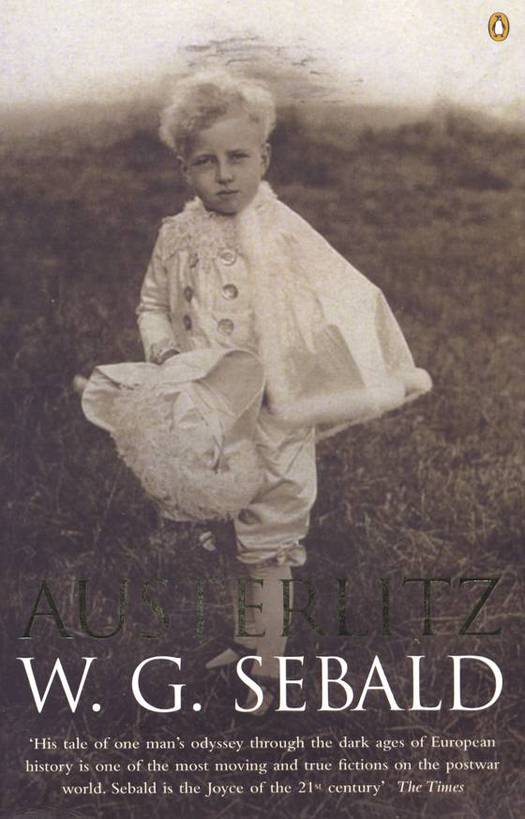

If Austerlitz is Sebald’s most sophisticated marriage of writing and imagery, its use of images also raises the most questions because, of all the books, it is the one most like a work of fiction, though of a highly unconventional kind. In 1939, not yet five, Jacques Austerlitz is sent to Britain on a Kindertransport and placed with foster-parents in Wales. Never happy, he excels at school and becomes an architectural historian. He is told nothing about his identity and it is years before he even learns his original name. Later, the past he has always avoided thinking about returns to haunt him and he goes in search of his lost parents. He relates this story in a series of sometimes coincidental meetings with the book’s narrator, who reports it to us. (Everything in Sebald is indirect. The narrator no more witnessed these events than we did.) British and American editions of Austerlitz show a photograph on the cover of a young boy dressed like a cavalier and our assumption that this must be Austerlitz proves correct. Yet, clearly, if Austerlitz is a fictional character, the picture must be of someone else. The status of many images in the book becomes equally questionable. In fact, the cover photograph is a boyhood picture of a real architectural historian, one of Sebald’s friends. Austerlitz is known to be a composite of several real people.

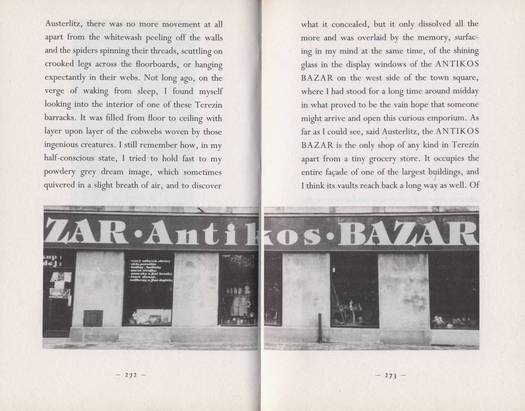

Austerlitz is always taking photographs and he entrusts his collection, which “one day would be all that was left of his life,” to the narrator, who uses them to assemble his story. After Austerlitz has a breakdown, some of his photographs play a therapeutic role, helping him to reconstruct his “buried experiences.” The book’s entire sequence of 87 images in 415 pages (Penguin UK edition) can be seen to serve a similar purpose. Here, more than ever, it seems clear that the images have not simply arrived after the writing was finished, to be used as “illustrations.”  Spread from Austerlitz, showing the files of prisoners held in the Small Fortress of Terezín

Spread from Austerlitz, showing the files of prisoners held in the Small Fortress of Terezín

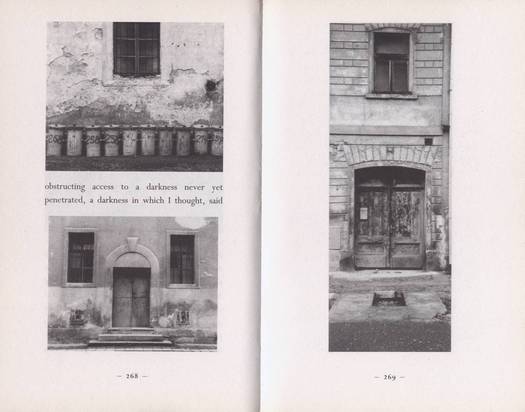

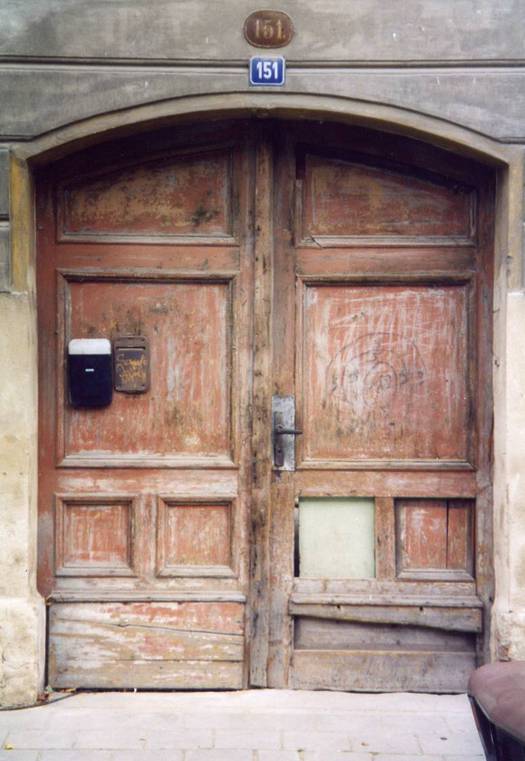

Sebald employs the pictures as a way of generating, one might even say designing, the meandering narrative. In one of the book’s most remarked-upon uses of photography, the text stops and Sebald shows a sequence of four doorways in Terezín, about 40 miles from Prague and site of a Jewish ghetto in the Second World War, which Austerlitz visits. (The town’s German name is Theresienstadt.) The brutal last door, with its heavy iron bands, cannot fail to suggest a death camp gas chamber, although no such thing is stated in the text.

The question of page design arises here. In a rare essay about the visual aspect of Sebald’s books, “Judging a book by its material embodiment,” Robin Kinross criticizes the crudity of design and production in the Harvill editions that introduced Sebald in Britain. Kinross notes that in The Rings of Saturn, some of the images have moved from their positions in the original German edition published by the Andere Bibliothek. What is not clear, however, is the extent to which Sebald was involved in the placement of these images in the original or subsequent editions. He is known to have been highly involved in the revision of his translations into English and French, so it seems unlikely, given the importance of the pictures, that he would have wanted no say in the matter. Like Austerlitz, he was a devoted photographer. “In school I was in the dark room all the time,” he told an interviewer, “and I’ve always collected stray photographs; there’s a great deal of memory in them.” He carried a small camera and was constantly on the lookout for old photos, postcards and newspaper cuttings. An obituary noted that, “He was an exacting customer at the University of East Anglia copy shop, discussing what might be done with his images, adjusting the size and contrast.” In the earlier books, the degraded, photocopied look of some of the pictures seems to have been a deliberate effect.

The Penguin design of Austerlitz shows a marked improvement on the Harvill volumes. The book takes the form of an almost continuous paragraph. One stupendous sentence unwinds over 11 pages, but the text is made much less overwhelming than this might sound by a narrow measure, generous line-spacing and ample margins. The pictures relate to this text area much more carefully than in the earlier English translations. The last three Terezín doors fill the height of the text column and all are cropped to the same narrow width — by Sebald? — like a series of tombstones. They become bleak and moving portents of the fate of Austerlitz’s family.

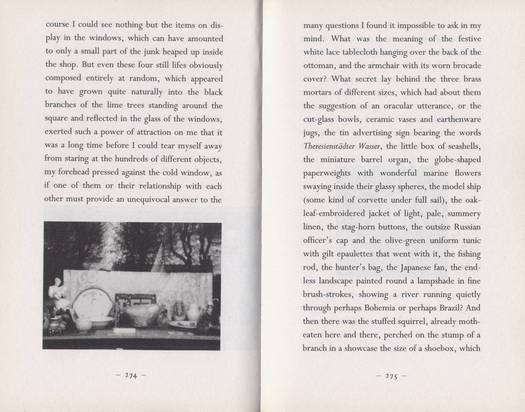

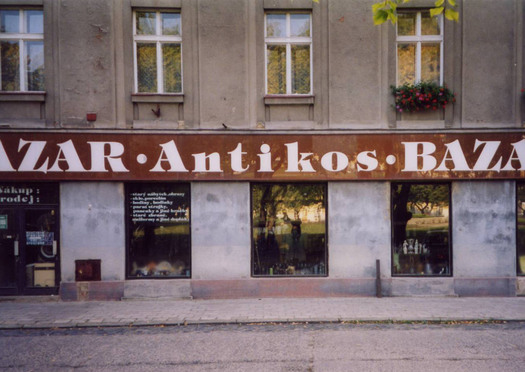

At one point, in a reverie, Austerlitz recalls the window displays of the Antikos Bazar, an antique shop on the west side of the town square in Terezín, where he had waited, hoping that someone would arrive to open the shop. Sebald shows a photograph of what he calls this “curious emporium” and the narrator describes the seemingly haphazard but, for him, highly mysterious and meaningful displays in the Bazar’s windows. This is illustrated with two more photographs.

Spreads from Austerlitz

Since I read this passage, my thoughts have sometimes returned to the Antikos Bazar. In 2004, I was in Prague, attending a conference, and it occurred to me that, if the shop existed where Sebald said it was, I now had the opportunity to see it for myself.

So, on a Saturday morning, I caught the bus from Prague to Terezín to find out how closely Sebald’s description of the town compared with reality. After travelling through the countryside for about an hour we pulled into the town square, and there, tucked away behind a fringe of trees on the far side, was the Antikos Bazar.

Terezín, 2004

The façade was in most respects the same as the one shown across two pages in Sebald’s book, but inevitably, after so long, the objects displayed in the four windows had changed. There was no sign that day of the three brass mortars “which had about them the suggestion of an oracular utterance,” of the “endless landscape painted round a lampshade in fine brush-strokes,” or of the moth-eaten stuffed squirrel “forever perched in the same position.” Remembering Austerlitz, with his face pressed against the glass, I lingered outside the Bazar, examining the sword sticks, hunting knives, military uniforms, field telephones, empty beer bottles, antlers, porcelain tea cups, crystal decanters, nude figurines and three waxy fish heads mounted on a wooden board that now filled the windows. Just as Sebald had described, at 11 o’clock in the morning the place was closed, making it impossible to explore the treasure trove of fishing rods, old wooden skis and bedpans that could be glimpsed in its deep, shadowy recesses through windows misted with condensation.

Window of the Antikos Bazar, 2004

Window of the Antikos Bazar, 2004

In other respects, Terezín was different from the book. It is raining when Austerlitz visits and he describes an oppressive, uncannily deserted town where he sees hardly anyone the entire time he is there apart from a man who is mentally disturbed. On the day I visited, people were on the move in the streets, though there was hardly any traffic and Terezín preserved a stillness that even the sound of techno music pounding from a battered car parked across the road from the Antikos Bazar could not dispel. Austerlitz records that the Bazar is the only shop of any kind except for a tiny grocery store. This intensifies the inaccessible emporium’s air of strangeness. Why is it there if it is rarely open for business and there are no customers? There are other shops nearby and it seems unlikely, given the size of the town, that there were only two shops when Sebald passed through. To a visitor’s eyes, however, these shops also possess an air of mystery, their façades painted with the same intense yellows, pinks and greens as the grand buildings in the square, their shop-front typography angular and strange.

Another thing I noticed, as I wandered around, was that the windows of these shops selling provisions presented the same kind of randomly organized tableaux of disparate things as the Antikos Bazar’s windows. The packages and containers on display brushed together behind the glass to suggest elusive kinds of significance and meaning, endowing ordinary household items with a heightened presence and a peculiar fascination. These whimsical, three-dimensional constructions, which might almost have been art works, betrayed an element of uninhibited expression that exceeded the requirements of commerce and conveyed a surprising degree of warmth. Shop window, Terezín, 2004

Shop window, Terezín, 2004

I had to move into the cobble-stoned side streets around Terezín’s town square to experience something closer to the mood of desertion that Sebald evokes. The plaster cladding along the lower parts of some of the walls has dropped off in great chunks, exposing the raw brickwork like skin torn from the surface of a wound.

Terezín, 2004

Terezín, 2004

Someone told me later that this was caused by the floods of 2002, which damaged Terezín as well as Prague, so the town must look more desolate now than it did when Sebald visited. Sebald has Austerlitz dwell at some length on the gates and doorways of Terezín, finding them the most uncanny aspect of the town — “all of them,” he writes, “obstructing access to a darkness never yet penetrated, a darkness in which I thought [. . .] there was no more movement at all.” He shows a series of haunting pictures of these apertures, and it is true that they do seem to be shut with a kind of brutal finality, sealing off whatever secrets they might hide, just like the Bazar does. Spread from Austerlitz

Spread from Austerlitz

Terezín, 2004

In Sebald’s novel, Austerlitz visits the Ghetto Museum (though not the nearby Small Fortress used by the Gestapo as a prison) and spends a long time looking at exhibits that document in overwhelming detail the lives of the ghetto’s Jewish prisoners and the history of their persecution. Emerging from the museum, he imagines that 60,000 people had never been taken away and are still living in the ghetto, crammed into the basements and attics, “a silent assembly, filling the entire space occupied by the air, hatched with grey as it was by the fine rain.” As I climb aboard the bus to return to Prague, the weather takes a turn for the worse and the first drops of rain start to fall.

This essay was first published in 2004 as two posts on Design Observer. I deleted it from the site when it appeared in Designing Pornotopia (2006). It is republished here with additional pictures.

Photographs of Terezín: Rick Poynor

See also:

On the Threshold of Sebald’s Room