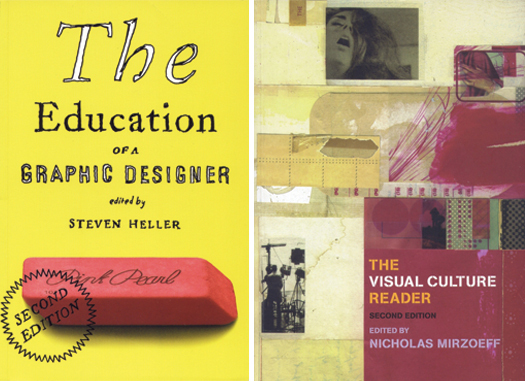

Cover designs by James Victore (left) and Nick Shah (right). Illustration by Michelle Thompson

Introduction: the reluctant discipline

Twenty years ago there was considerable optimism about the possibility that graphic design history would become a fully-fledged academic discipline, despite some unresolved questions about its purpose. Although there has been some progress toward this goal in the past two decades, these developments have taken place at a slower pace than might once have been expected.[1] As a discipline — if this is even the right term to use — graphic design history is still in a state of becoming, and there are good reasons to ask whether, on its present course, it will ever achieve the maturity that some observers hoped for.

This lack of progress might be measured in various ways. Most obviously, in Britain, where I write, there is no such thing as a first degree in graphic design history. Even design history studied as a clearly defined degree subject concerned with largely non-graphic forms of design remains a rarity.[2] The subject is usually combined with art history and sometimes with film history.[3] Art history established itself several decades ago as a coherent academic discipline and as a subject for study with a broad appeal to non-practitioners. Design history has a long way to go to achieve the same stature or pulling power.

The situation is not much better when it comes to graphic design history writing — which is not surprising because the need for such research is inevitably linked to the amount of study taking place in higher education. The key indicator of the discipline’s health is book publishing. Although academic papers about aspects of graphic design history are delivered at conferences and surface in publications such as Design Issues and Journal of Design History, we should be wary of mistaking these occasional expressions of interest in graphic design history for signs of much activity in the field. Perhaps the most striking example of this shortfall is the three issues of Visible Language published in 1994-5, which set out to explore the possibility of new “critical histories of graphic design.”[4]

This ambitious project appeared to promise a dawning era of intellectually challenging, revisionist graphic design history writing that would in time have a significant effect on the field of book publishing — even transforming perceptions of what such writing could be; but this promise did not come to fruition. Only a minority of the 15 Visible Language contributors went on to make substantial contributions to graphic design history, in terms of scholarly research that led to the publication of original, authoritative, subject-redefining books.[5] This is not to say that there have been no other significant additions to the graphic design history bookshelf during the past decade, but even in a good year, the additions never amount to more than a few titles.[6] When this patchy output is placed beside the numerous books produced by scholars working in, for instance, the fields of art, architecture, or film, as it is in any visual arts bookshop, it becomes obvious that graphic design history as a terrain for intensive and sustained research and study barely exists at all.

The reasons why graphic design history has failed to develop — and, without a change of direction, will most likely continue to fail to develop — are sometimes acknowledged in passing but are not addressed with any persistence or rigor, perhaps because they point to some unwelcome conclusions for the subject as it is currently situated and being taught. In an attempt to see the problem more clearly, this essay revisits some of these perspectives. The essay’s second aim, arising from this review, is to propose an alternative site of production for graphic design history, albeit one that is interdisciplinary in essence rather than located within its own clearly delineated departmental borders. Graphic design history’s best chance of development now lies in an expanded conception of the rapidly emerging discipline of visual culture or visual studies.[7] Although this proposal is also problematic, for reasons that will be explored, only in visual studies might graphic design history be able to establish the interdisciplinary connections necessary for it to fulfill its early promise and to grow.

Graphic design history is for graphic designers

Almost all of the early arguments about the need for graphic design history were made from within the discipline of graphic design by informed observers, often graphic designers, who felt that knowledge of graphic design’s history and development was essential for any practitioner. This grounding would allow graphic designers to avoid plagiarism and pointless reinvention; it would supply “inspiration” and give them a legacy on which to build. Steven Heller sets out this position in his introduction to Graphic Design History, a book of essays about design history subjects intended for graphic design students:

A compelling case has been made through conferences, magazine articles, and books, for the centrality of graphic design history in the education of all graphic designers. During this formative period in the digital age, when new media is altering traditional notions of graphic design practice, it is even more important that designers have the grounding provided by historical knowledge.[8]

Andrew Blauvelt, editor of the three “critical histories” issues of Visible Language, put the issue even more strongly; writing two years after the trilogy appeared, he went so far as to assert that the only plausible use for graphic design history was as a tool for educating graphic designers more effectively:

The notion of design as a field of study without practical application is unlikely and undesirable. After all, it is the practice of graphic design — no matter how wanting or limiting — that provides the basis for a theory of graphic design. [. . .] The calls for graphic design to be a liberal art — a quest for academic legitimacy — need to be supplanted by strategies which foster “critical making,” teaching when, how, and why to question things.[9]

Indeed, at least one call for design to be considered as a liberal art had been made, but this tendency hardly needed to be supplanted because the design-history-is-for-designers point of view has always dominated discussion.[10] This design studio orientation is only to be expected because those who write about the possibilities of graphic design history are usually graphic designers who, if they also teach, are almost always situated within graphic design departments. However, the idea that design history, pursued as an academic end in itself, could lead to estrangement from the methods and goals of design practice has also been proposed by professional historians who might seem to have every reason to wish to construct design history as a separate enclave. Guy Julier and Viviana Narotzky note “a yawning gap between the desires of design historians and the actions of designers,” suggesting that design history might have made itself redundant as a contributor to essential principles of practice.[11] They conclude: “We do not question the value of history as discourse [. . .] But we do ask design history to return to its roots and bed itself with practice.”[12] Whatever relevance this request might have had for historians concerned with industrial design, for graphic design it could be taken as little more than a warning for graphic design history to stay where it was already situated — in bed with practice.

However, this location was by no means as secure, congenial, or productive for the incubation of graphic design history as it might sound. In the way that they are usually constituted and administered, graphic design departments have some profound limitations as homes for historical study. As Heller observes, most American design schools do not use dedicated teachers of design history; in fact, most design history teachers are “practitioners who have entered the field through the back door,” without experience in historical research and publishing, and most design schools, even if they offer a few graphic design history courses, do not have the finances to maintain a dedicated history program.[13]

Louis Danziger, described by Heller as one of the first “historian-cum-practitioners” to introduce a class in graphic design history, is frank about the limitations of his own design history teaching, acknowledging that it is neither academic nor scholarly and is primarily concerned with helping students to enhance their performance as designers. Danziger claims that practitioners cannot be good historians because their experience “inevitably introduces biases,” and they “cannot be objective.”[14] The British design educator Jonathan Baldwin has expressed similar concerns about the situation in Britain, where design history is often taught by part-timers on hourly contracts, and studio staff and students see design history as disconnected from the practical side of their courses. “If [design history] is so unimportant that staff are paid by the hour and only during term-time, it’s obviously not [seen as] important at all,” he writes.[15]

All of these perspectives begin to explain why, despite the energetic and optimistic support of a few notable proponents, graphic design history has progressed so slowly. For the most part, the subject remains essentially an afterthought, a comparatively minor adjunct to the design studio, conceived by its apologists as a means of molding better-rounded graphic designers but still seen as irrelevant by many students obliged to take these classes, and permanently undernourished by a lack of institutional support.

Publishers are fully aware of graphic design history’s lack of presence and status as an academic subject, and the small number that are prepared to take the risk and produce books about graphic design history know from experience that the market for these studies remains small. Such books can only do well if they are placed on course reading lists, but the more specialized the subject matter, the less likely this placement is to happen, leading publishers to favor bland visual surveys with the widest possible appeal. At the same time, the number of teachers with the motivation, talent and pressing career reasons to undertake ambitious research projects is tiny compared to other, better established and more academically grounded visual arts subjects. Graphic designers with commercial practices to maintain, in addition to their teaching duties, have little time to engage in protracted historical research and writing, even if they possess an aptitude for it.

Visual studies’ mysterious blind spot

With graphic design history still not fully formed as a subject, it might seem that continuing calls to reform it, to introduce “new perspectives” and “new views,” can only fall on stony ground, no matter how well intentioned. Who is to do the reforming, and to what end? Is there any reason to suppose that the personal and institutional factors that have inhibited graphic design history’s growth in its unreformed state will not continue to inhibit any widespread adoption and application of new thinking within the field? Or will these new impulses by their very nature somehow succeed in lifting graphic design history — still positioned where it always has been as a studio add-on — to a higher plane of perceived relevance, productivity and academic attainment?

The primary contention of the critiques originating within design is that it is not enough for design history to concern itself with the evolution of graphic styles as seen in the work of a canonical list of heroic (white, male) designers. Meggs’ A History of Graphic Design (1983) is generally cited as the work that enshrines this Pevsnerian view of graphic design history.[16] Many design teachers have drawn attention to the limitations of this approach; two examples will suffice. Baldwin suggests that the slideshow parade of “great” historical moments, with its emphasis on long lists of unfamiliar names, facts, and dates that must be committed to memory, is thoroughly off-putting to students, who fail to see its relevance to their studio-based studies and future activities as designers. Instead, he suggests, design history should adopt what he calls “history-less history,” which looks at history as a series of causes and effects with particular emphasis on the systems of production and consumption of design. This perspective allows us to bring in social studies, cultural studies, psychology, audience studies, politics and issues that are often ignored: ethics and human ecology.[17]

Prasad Boradkar, writing in The Education of a Graphic Designer, likewise moves the emphasis to the contexts of graphic communication’s production, arguing that this theme be “situated within a variety of venues, including cultural, social, political, environmental, and economic contexts.”[18] Similarly, he invokes a list of adjacent disciplines and areas of study that could function as valuable resources, including visual culture, media and cultural studies, anthropology, material culture and sustainability studies.

Although any of these disciplines might offer methods, perspectives, and insights for understanding graphic design history, most of them are clearly unsuitable as alternative resting places for the discipline’s study. As Robin Kinross has remarked with obvious irony, in the early 1990s it seemed that, at least in Britain, cultural studies would “take care of graphic design, seeing it as just one more item in the total menu of ‘culture.’”[19] In the past decade, however, visual studies, rather than cultural studies, has emerged as the discipline with aspirations to take care of every aspect of the visual realm, and it might have seemed inevitable that graphic design’s outputs, as omnipresent phenomena in this realm, would fall under its gaze. However, this has not as yet happened. It is rare for books about visual culture to include even the briefest discussion of design, while graphic design usually goes entirely unremarked — an omission that can only be described as astonishing, bearing in mind visual studies’ overarching ambitions.[20]

Perhaps the most emblematic example of this oversight is The Visual Culture Reader, edited by Nicholas Mirzoeff. This much-reprinted title finds no space for any discussion of graphic design among the 60 texts that fill its 740 pages — not even in the section concerned with “spectacle and display.”[21] Not a single writer associated with graphic design history, theory, or commentary contributed to the book. When visual culture writers summarize the areas that concern the new discipline, graphic design is not one of them. Martin Jay writes that visual culture is “located somewhere at the crossroads of traditional art history, cinema, photography, and new media studies, the philosophy of perception, the anthropology of the senses, and the burgeoning field of cultural studies . . ..”[22] Margaret Dikovitskaya sees it as arising from the convergence of art history, anthropology, film studies, linguistics and comparative literature after they encountered poststructuralist theory and cultural studies.[23] On the rare occasions when specifically graphic forms of visual culture are discussed, the new discipline’s leading lights can sound oddly distant and uncertain, as though they have little precise contextual awareness of the object of study:

[W]hen I look through certain magazines, I am always struck by the manner in which the impact of what is on a page seems to be more due to the images and the typeface and glaring visual stimuli, than to the substance of the arguments and the meanings of the words themselves. However, too much postmodern writing seems to hide itself behind the pyrotechnics of postmodern visuality. This may be generational: younger people seem more comfortable with it than older people, since perhaps their greater exposure to computer games and other modern mass media has made them a little more visual.[24]

For anyone located within design, visual studies’ failure to acknowledge and address the central role of graphic design as a shaper of the visual environment, alongside the forms of visual culture that it does acknowledge — art, film, television, photography, advertising, new media — must seem unaccountable. What could explain this peculiar blindness among a group of academics hyper-attuned to most forms of visuality?

One point that is immediately clear is that the oversight duplicates a wider public oversight — the oft-remarked “transparency” or “invisibility” of graphic communication — that has long been a source of concern among designers. It is still unusual for graphic design to be discussed anywhere other than in professional publications and a few academic journals; in addition, oversight by the media begets oversight by the public (even by academics in neighboring disciplines), so that the vast majority of people are not accustomed to thinking of graphic design as a vital part of culture worthy of continuous (or even sporadic) comment.[25]

Even more significant, however, are the departmental factors discussed earlier. Many of visual studies’ leading figures come from art history and evidently lack even the most basic knowledge of design history. Graphic design history’s compromised location as an adjunct to the design studio — its lack of full departmental status — denies it the appearance of academic legitimacy. In addition, the inward-looking nature of graphic design history writing and other forms of design discourse, and the continuing assumption among designer writers that the ultimate purpose of such commentary is professional improvement, has created a body of writing that appears from the outside, when it is noticed at all, to be merely of professional interest. If graphic design history books are being consulted by academics working in visual studies, they certainly are not being cited regularly. Before graphic design history writing can connect with a wider academic readership, it needs to orient itself differently — no small task at even the most elementary level of distribution. Bookshops struggle with the idea of interdisciplinarity when it comes to classifying and shelving a book. Even design titles purposefully aimed in part at cultural studies or visual studies readers can end up in the design section, where they are less likely to be encountered by readers who are not designers.[26]

Does visual culture have a history?

Unpromising as its resistance to design might sound, visual studies nevertheless has the potential to offer the most propitious base, outside the design studio, for new critical approaches to graphic design history. To understand how graphic design might fit into visual studies, we need to consider its underlying principles. Any view can only be provisional because, as a new subject, visual studies is in a state of flux and because, despite many shared assumptions, its proponents differ on some key questions. One point they tend to agree on is that culture has taken a “visual turn”: that the visual is ever more dominant in contemporary society, both as a means of communication and as a source of meaning.[27] While this process began with industrialization and accelerated throughout the 20th century, digital technology pushed the production, dissemination, and use of imagery to a new level of reach and saturation. The fusion of media made possible by digital technology mandates the convergence within visual studies of critics, historians and practitioners who reject the received ideas of the established disciplines they come from.[28] Visual studies directs its attention to the visual as a place where, in Mirzoeff’s words, “meanings are created and contested.”[29]

Julier has characterized visual studies as occupying “the enervated position of the detached or alienated observer overwhelmed by images.”[30] But this complaint underplays the fact that the images are already out there circulating and disregards the possibility that they might be problematic. According to Mirzoeff, “visual culture is a tactic with which to study the genealogy, definition, and functions of postmodern everyday life from the point of view of the consumer, rather than the producer.”[31] Far from encouraging enervation, the educational aim of visual studies is, then, essentially positive: to produce active, skeptical viewers equipped to respond critically to the visual imagery that surrounds us. This viewpoint immediately puts the analytical emphasis exactly where many critics of graphic design commentary and history say they wish it to be. Instead of focusing on the designer, a visual culture approach to design would focus on the effects of design as everyday, visual communication on its audiences. As Mirzoeff explains, visual culture is not concerned with the structured, formal viewing that takes place in a cinema or art gallery, but rather with the visual experience in everyday life: “from the snapshot to the VCR and even the blockbuster art exhibition.”[32]

Although this brief list typically privileges forms of visual material (e.g., photography, film, art) that tend to predominate in visual studies, we might just as plausibly add wall posters, magazine layouts, luxury goods packaging, or postage stamps. Graphic design has been overlooked precisely because it forms the connective tissue that holds so many ordinary visual experiences together. We don’t usually view a professional photograph in isolation: We view it as part of a page, screen, billboard, or shop window display in relationship with other pictorial, typographic and structural elements determined in the design process. These frameworks and relationships are an indivisible part of the meaning.

Where the theorists of visual studies sometimes part company is in their view of the extent to which the field should concern itself with history. Irit Rogoff is emphatic in distinguishing between her work on visual culture and her early approach as an art historian:

The field that I work in [. . .] does not function as a form of art history or film studies or mass media, but is clearly informed by all of them and intersects with all of them. It does not historicize the art object or any other visual image, nor does it provide for it either a narrow history within art nor a broader genealogy within the world of social and cultural developments. It does not assume that if we overpopulate the field of vision with ever more complementary information, we shall actually gain any greater insight into it.[33]

Such a view might be welcomed by supporters of “history-less history,” but it poses some problems for graphic design history. As Dikovitskaya notes, an academic field is defined by three criteria: “the object of study, the basic assumptions that underpin the methods of approach to the object, and the history of the discipline itself.”[34] Compared to art history, the project of graphic design history is still at a formative stage, and this is one reason why the subject has low visibility for people in visual studies. Only in recent years, more than two decades after the arrival of Meggs’ history, have several similarly scaled rival volumes emerged.[35] By the time radical art historians developed the new art history in the 1970s, with its emphasis on the social production of art, the art libraries of the world were already stocked with conventional art histories. In other words, there was already a structure of basic information and an interpretive framework in place for the new wave of historians to revise.[36]

In the graphic design field, however, historical information is still lacking about even the most notable subjects, “narrow” as such scholarship might appear. Many significant but lesser known figures are overlooked.[37] Given the difficulties of publication already outlined, the arrival of any well-researched volume of graphic design history signifies a triumph against the odds. Rogoff argues persuasively that it is “the questions that we ask that produce the field of inquiry and not some body of materials which determines what questions need to be posed to it.”[38] Nevertheless, she also acknowledges the danger that casting aside historical periods, schools of style, and the possibility of reading objects through conditions of production might entail losing a firm sense of “self location.”[39] Divesting graphic design of its historical sign posts and landmarks would be enormously risky for a subject that is shakily located and barely apparent to those outside the field in the first place.[40]

Mirzoeff notes that graduate students approaching visual studies are sometimes worried about what body of material they are supposed to know; their concern instead, he asserts, should be with the questions they want to generate. The focus then moves to finding the most appropriate methods to answer those questions and to locating the sources that can lead to discovering the answers.[41] In a field as broad, provisional and unstable as visual culture, where visual media and their uses change all the time, the traditional pursuit of encyclopedic knowledge is no longer tenable. The history of modern media must be understood collectively rather than as a series of discrete disciplinary units, such as art, film and television (or for that matter, graphic design).

Nevertheless, in Mirzoeff’s view, historical inquiry remains central to an understanding of visual culture because signs are always contingent and can only be understood in their historical contexts.[42] If art history, film studies and media studies are going to be taught together under the heading of visual studies, then new integrative histories of visual media must be written, necessitating much new research. W.J.T. Mitchell, one of visual studies’ most influential figures, is similarly committed to the idea of a defined and teachable history, wanting students who take his courses to understand that “visual culture has a history, that the way people look at the world and the way they represent it changes over time, and that this can actually be documented.”[43] According to Mitchell, the idea that visual studies seeks to take an unhistorical approach to vision is a myth.[44]

Conclusion: history leaves the studio?

It should be clear even from this brief overview that there is no intrinsic reason why graphic design history (and graphic design studies) should not form part of visual studies’ purview. Every indication suggests that visual studies will become increasingly well established in the years ahead. Economic factors to do with student preferences cannot be ignored, and in the United States, the subject attracts students who are not necessarily interested in the specialized forms of knowledge offered by traditional visual disciplines.[45] Visual studies connects with visual media experiences familiar to everyone in a way that art history does not. Its burgeoning introductory literature attests to its popularity, as well as its intellectual vigor. For teachers coming to visual studies from other disciplines, it offers ways of understanding visual media more closely related to the overlapping, interlocking, hybrid nature of contemporary visual experience. It would be a strange oversight — to the point of undermining visual studies’ claims of integrative purpose — if its theorists were to continue to overlook and thereby discount graphic communication’s central participation in the creation of the image world.

This proposal is not to suggest that graphic design history does not have a place in the studio as an essential part of any graphic design student’s understanding of the discipline. History-conscious teachers of graphic design no doubt will continue to argue that the subject be taken seriously and given adequate funding and support within design schools, and they are right to do so. However, a view of graphic design history that sees it as being only, or even primarily, for the purpose of educating graphic designers and that seeks to confine it to the design studio will continue to restrict the development of the subject in the ways described here. If graphic design is a truly significant cultural, social, and economic force, then it has the potential to be a subject of wider academic (and public) interest, but it will need to be framed and presented in ways that relate to the concerns of viewers who are not designers — that is, to most viewers. As habitually inward-looking custodians of their own history, few graphic design educators have proven to be effective at this outward-looking, viewer-oriented style of writing and public address.[46]

Design educators need to foster this ability because until graphic design teachers with historical and theoretical insights begin to build a bridge toward visual studies — by writing for its journals and presenting papers at its conferences, and by demonstrating graphic design’s interest and significance through the strength of their scholarship — there is little prospect that visual studies will expand to include it. Although there are comparatively few academically trained design historians who concentrate on graphic design history (which is also a matter for concern), they, too, could redirect some of their output toward visual studies.

In the short term, this movement toward visual studies would not mean abandoning graphic design departments as places of “self location,” but it would certainly require self-questioning and self-reinvention, starting with a close engagement with the thinking and literature of visual studies, which has barely been mentioned to date in historical and critical writing about graphic design. There are reasons, in any case, as we have seen, to anticipate that less designer-centric and fact-heavy ways of addressing the subject and investigating its social meanings would make graphic design history more appealing and useful to design students. Only when graphic design as an existing object of study becomes more visible will visual studies scholars who have come from other disciplines begin to see it as a potential field of inquiry alongside more clearly perceived visual media. The study of graphic design surely would benefit from opening itself up to these new interdisciplinary perspectives and investigations from the outside.

It might be argued that the partial absorption of graphic design history by visual studies would involve a crucial loss of autonomy. Art historians have certainly voiced fears that the renegade proponents of the new visual studies risk undoing their discipline.[47] In the case of graphic design history, however, there isn’t a unified discipline to undo. Graphic design history exists between the cracks. It is not likely to achieve independence as a department in most institutions anytime soon, and, as things stand, it will continue to camp out in the studio. It is a late-starter with a lot of catching up to do.

Visual studies is an even newer arrival, although it has an energy and sense of purpose that comes from soaking up the strength of other disciplines with a long pedigree and deep theoretical foundations. Yet visual studies also exists in the gaps between other less adaptable fields of study, with an uncertainty, a lack of firm adhesion, that only makes it feel more timely and relevant. If graphic design history could find a second outpost within this territory, the making of the subject could prove — at last — to be a possibility.

Thanks to the Royal College of Art, London, where a research fellowship made this research possible, and to Teal Triggs at the London College of Communication for inviting me to speak at New Views: Repositioning Graphic Design History, the starting point for this essay.

Notes and links

1. See, for instance, Journal of Design History 5:1 (1992), a special issue devoted to graphic design history.

2. In the United Kingdom, Brighton University offers a well-established BA in History of Design, Culture, and Society. The Royal College of Art, in association with the Victoria and Albert Museum, offers a well-established MA in History of Design.

3. Examples of combined BA courses in the United Kingdom include: History of Art, Design, and Film (Kingston University), History of Art and Design (Manchester Metropolitan University), History of Modern Art, Design, and Film (Northumbria University).

4. Visible Language, special issues: “New Perspectives: Critical Histories of Graphic Design,” Andrew Blauvelt, guest ed. 28:3 (1994), 28:4 (1994), 29:1 (1995). See also Andrew Blauvelt, “Designer Finds History, Publishes Book,” Design Observer (2010).

5. See Victor Margolin, The Struggle for Utopia: Rodchenko, Lissitzky, Moholy-Nagy 1917-1946 (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1997), Deborah Rothschild, Ellen Lupton and Darra Goldstein, Graphic Design in the Mechanical Age: Selections from the Merrill C. Berman Collection (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1998), Martha Scotford, Cipe Pineles: A Life of Design (New York: W.W. Norton, 1999).

6. Since 2005 see, for instance, Michel Wlassikoff, The Story of Graphic Design in France (Corte Madera: Gingko Press, 2005), Stanislaus von Moos, Mara Campana and Giampiero Bosoni, Max Huber (London and New York: Phaidon Press, 2006), Richard Hollis, Swiss Graphic Design: The Origins and Growth of an International Style (London: Laurence King Publishing, 2006), Kerry William Purcell, Josef Müller-Brockmann (London and New York: Phaidon Press, 2006), R. Roger Remington and Robert S.P. Fripp, Design and Science: The Life and Work of Will Burtin (Aldershot: Lund Humphries, 2007), Laetitia Wolff, Massin (London and New York: Phaidon Press, 2007), Steven Heller, Iron Fists: Branding the 20th-Century Totalitarian State (London and New York: Phaidon Press, 2008).

7. I shall follow W.J.T. Mitchell’s distinction and use “visual studies” for the field of study and “visual culture” for the object or target of study. Some writers on visual culture, including Mitchell, prefer to use “visual culture” interchangeably. See Mitchell, “Showing Seeing: A Critique of Visual Culture” in The Visual Culture Reader, Nicholas Mirzoeff ed. (London and New York: Routledge, 2nd ed. 2002): 87. On visual culture, in addition to the other works cited here, see Block Editorial Board and Sally Stafford, The Block Reader in Visual Culture (London and New York: Routledge, 1996), John A. Walker and Sarah Chaplin, Visual Culture: An Introduction (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997), Malcolm Barnard, Approaches to Understanding Visual Culture (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2001), James Elkins, Visual Studies: A Skeptical Introduction (New York and London: Routledge, 2003).

8. Steven Heller in Graphic Design History, Steven Heller and Georgette Ballance, eds. (New York: Allworth Press, 2nd ed. 2001): viii.

9. Andrew Blauvelt, “Notes in the Margin,” Eye 6:22 (1996): 57.

10. Gunnar Swanson, “Graphic Design Education as a Liberal Art: Design and Knowledge in the University and the ‘Real World’” in The Education of a Graphic Designer, Steven Heller ed. (New York: Allworth Press, 2005): 22-32.

11. Guy Julier and Viviana Narotzky, “The Redundancy of Design History” (Leeds Metropolitan University, 1998).

12. Ibid.

13. Heller, “The Case for Critical History” in Graphic Design History, 94.

14. Louis Danziger, “A Danziger Syllabus” in The Education of a Graphic Designer, 333.

15. Jonathan Baldwin, “Abandoning History,” A Word in Your Ear (2005). Baldwin delivered a paper on this theme at New Views: Repositioning Graphic Design History (London College of Communication, 27-29 October 2005).

16. Philip B. Meggs, A History of Graphic Design (New York: John Wiley, 3rd ed. 1998, 4th ed. 2005).

17. Baldwin, “Abandoning History.”

18. Prasad Boradkar, “From Form to Context: Teaching a Different Type of Design History” in The Education of a Graphic Designer, 85. For further discussion of the problems arising from the “varied discursive locations of visual design activity,” see Victor Margolin, “Narrative Problems of Graphic Design History,” Visible Language 28:3 (1994): 233-43.

19. Robin Kinross, “Design History: No Critical Dimension,” AIGA Journal of Graphic Design 11:1 (1993): 7.

20. One exception is the British writer Malcolm Barnard. See Art, Design and Visual Culture: An Introduction (Basingstoke: Macmillan Press, 1998). Barnard went on to write Graphic Design as Communication (London and New York: Routledge, 2005).

21. Nicholas Mirzoeff ed., The Visual Culture Reader (London and New York: Routledge, 2nd ed. 2002).

22. Martin Jay, “Introduction to Show and Tell,” Journal of Visual Culture, “The Current State of Visual Studies” 4:2 (2005).

23. Margaret Dikovitskaya, Visual Culture: The Study of the Visual after the Cultural Turn (Cambridge and London: MIT Press, 2005): 1.

24. Martin Jay (interview) in Visual Culture: The Study of the Visual after the Cultural Turn, 206.

25. A significant public “breakthrough” moment for graphic design was the international release in 2007 of the feature-length documentary, Helvetica, directed by Gary Hustwit. Reviewers with no specialized knowledge of design noted that it had made them look at aspects of the visual environment usually taken for granted with a new level of attention and understanding. See, for instance, the Metromix Chicago review (2007).

26. I have personal experience of this classification problem. See Rick Poynor, Obey the Giant: Life in the Image World (Basel: Birkhäuser, 2007) and Designing Pornotopia: Travels in Visual Culture (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2006).

27. See Martin Jay, “That Visual Turn: The Advent of Visual Culture,” Journal of Visual Culture 1:1 (2002): 87-92.

28. Mirzoeff, The Visual Culture Reader, 6.

29. Nicholas Mirzoeff, An Introduction to Visual Culture (London and New York: Routledge, 1999): 6. See also the substantially revised second edition, 2009.

30. Guy Julier, “From Visual Culture to Design Culture,” Design Issues 22:1 (2006): 76.

31. Mirzoeff, An Introduction to Visual Culture (1999), 3.

32. Ibid, 7.

33. Irit Rogoff, “Studying Visual Culture” in The Visual Culture Reader, 27.

34. Dikovitskaya, Visual Culture: The Study of the Visual after the Cultural Turn, 4.

35. Roxane Jubert, Typography and Graphic Design: From Antiquity to the Present (Paris: Flammarion, English ed. 2006), Stephen J. Eskilson, Graphic Design: A New History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), Johanna Drucker and Emily McVarish, Graphic Design History: A Critical Guide (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2008) and Patrick Cramsie, The Story of Graphic Design (New York: Abrams, 2010). For extended discussion of Eskilson, see Alice Twemlow and Lorraine Wild, “A New Graphic Design History?” Design Observer (2007). For extended discussion of Drucker and McVarish, see Denise Gonzales Crisp and Rick Poynor, “A Critical View of Graphic Design History,” Design Observer (2008).

36. See Jonathan Harris, The New Art History: A Critical Introduction (London and New York: Routledge, 2001).

37. See Andrew Blauvelt, “Modernism in the Fly-Over Zone,” Design Observer (2007).

38. Gayatri Spivak quoted by Rogoff, The Visual Culture Reader, 26.

39. Rogoff, The Visual Culture Reader, 33.

40. For further reflections on this oversight, see Johanna Drucker, “Who’s Afraid of Visual Culture,” Art Journal 58:4 (1999): 36-47.

41. Mirzoeff (interview) in Visual Culture: The Study of the Visual after the Cultural Turn, 232.

42. Mirzoeff, An Introduction to Visual Culture (1999), 14.

43. Mitchell (interview) in Visual Culture: The Study of the Visual after the Cultural Turn, 256.

44. Mitchell, The Visual Culture Reader, 90.

45. See Mirzoeff and Mitchell in Visual Culture: The Study of the Visual after the Cultural Turn, 227-31, 243, 255-7.

46. Exceptions should be noted, in particular the work of Ellen Lupton, curator since 1992 of exhibitions about graphic design for the public at the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum. Lupton’s practice as designer, educator, curator and writer provides a paradigm for a more publicly oriented presentation of graphic design. As design director of the Walker Art Center, Andrew Blauvelt also assumed a curatorial role. In 2010, he was appointed chief of communications and audience engagement at the center.

47. See “Visual Culture Questionnaire,” October 77 (1996): 25-70. In particular, see Thomas Crow: 36.

1. See, for instance, Journal of Design History 5:1 (1992), a special issue devoted to graphic design history.

2. In the United Kingdom, Brighton University offers a well-established BA in History of Design, Culture, and Society. The Royal College of Art, in association with the Victoria and Albert Museum, offers a well-established MA in History of Design.

3. Examples of combined BA courses in the United Kingdom include: History of Art, Design, and Film (Kingston University), History of Art and Design (Manchester Metropolitan University), History of Modern Art, Design, and Film (Northumbria University).

4. Visible Language, special issues: “New Perspectives: Critical Histories of Graphic Design,” Andrew Blauvelt, guest ed. 28:3 (1994), 28:4 (1994), 29:1 (1995). See also Andrew Blauvelt, “Designer Finds History, Publishes Book,” Design Observer (2010).

5. See Victor Margolin, The Struggle for Utopia: Rodchenko, Lissitzky, Moholy-Nagy 1917-1946 (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1997), Deborah Rothschild, Ellen Lupton and Darra Goldstein, Graphic Design in the Mechanical Age: Selections from the Merrill C. Berman Collection (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1998), Martha Scotford, Cipe Pineles: A Life of Design (New York: W.W. Norton, 1999).

6. Since 2005 see, for instance, Michel Wlassikoff, The Story of Graphic Design in France (Corte Madera: Gingko Press, 2005), Stanislaus von Moos, Mara Campana and Giampiero Bosoni, Max Huber (London and New York: Phaidon Press, 2006), Richard Hollis, Swiss Graphic Design: The Origins and Growth of an International Style (London: Laurence King Publishing, 2006), Kerry William Purcell, Josef Müller-Brockmann (London and New York: Phaidon Press, 2006), R. Roger Remington and Robert S.P. Fripp, Design and Science: The Life and Work of Will Burtin (Aldershot: Lund Humphries, 2007), Laetitia Wolff, Massin (London and New York: Phaidon Press, 2007), Steven Heller, Iron Fists: Branding the 20th-Century Totalitarian State (London and New York: Phaidon Press, 2008).

7. I shall follow W.J.T. Mitchell’s distinction and use “visual studies” for the field of study and “visual culture” for the object or target of study. Some writers on visual culture, including Mitchell, prefer to use “visual culture” interchangeably. See Mitchell, “Showing Seeing: A Critique of Visual Culture” in The Visual Culture Reader, Nicholas Mirzoeff ed. (London and New York: Routledge, 2nd ed. 2002): 87. On visual culture, in addition to the other works cited here, see Block Editorial Board and Sally Stafford, The Block Reader in Visual Culture (London and New York: Routledge, 1996), John A. Walker and Sarah Chaplin, Visual Culture: An Introduction (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997), Malcolm Barnard, Approaches to Understanding Visual Culture (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2001), James Elkins, Visual Studies: A Skeptical Introduction (New York and London: Routledge, 2003).

8. Steven Heller in Graphic Design History, Steven Heller and Georgette Ballance, eds. (New York: Allworth Press, 2nd ed. 2001): viii.

9. Andrew Blauvelt, “Notes in the Margin,” Eye 6:22 (1996): 57.

10. Gunnar Swanson, “Graphic Design Education as a Liberal Art: Design and Knowledge in the University and the ‘Real World’” in The Education of a Graphic Designer, Steven Heller ed. (New York: Allworth Press, 2005): 22-32.

11. Guy Julier and Viviana Narotzky, “The Redundancy of Design History” (Leeds Metropolitan University, 1998).

12. Ibid.

13. Heller, “The Case for Critical History” in Graphic Design History, 94.

14. Louis Danziger, “A Danziger Syllabus” in The Education of a Graphic Designer, 333.

15. Jonathan Baldwin, “Abandoning History,” A Word in Your Ear (2005). Baldwin delivered a paper on this theme at New Views: Repositioning Graphic Design History (London College of Communication, 27-29 October 2005).

16. Philip B. Meggs, A History of Graphic Design (New York: John Wiley, 3rd ed. 1998, 4th ed. 2005).

17. Baldwin, “Abandoning History.”

18. Prasad Boradkar, “From Form to Context: Teaching a Different Type of Design History” in The Education of a Graphic Designer, 85. For further discussion of the problems arising from the “varied discursive locations of visual design activity,” see Victor Margolin, “Narrative Problems of Graphic Design History,” Visible Language 28:3 (1994): 233-43.

19. Robin Kinross, “Design History: No Critical Dimension,” AIGA Journal of Graphic Design 11:1 (1993): 7.

20. One exception is the British writer Malcolm Barnard. See Art, Design and Visual Culture: An Introduction (Basingstoke: Macmillan Press, 1998). Barnard went on to write Graphic Design as Communication (London and New York: Routledge, 2005).

21. Nicholas Mirzoeff ed., The Visual Culture Reader (London and New York: Routledge, 2nd ed. 2002).

22. Martin Jay, “Introduction to Show and Tell,” Journal of Visual Culture, “The Current State of Visual Studies” 4:2 (2005).

23. Margaret Dikovitskaya, Visual Culture: The Study of the Visual after the Cultural Turn (Cambridge and London: MIT Press, 2005): 1.

24. Martin Jay (interview) in Visual Culture: The Study of the Visual after the Cultural Turn, 206.

25. A significant public “breakthrough” moment for graphic design was the international release in 2007 of the feature-length documentary, Helvetica, directed by Gary Hustwit. Reviewers with no specialized knowledge of design noted that it had made them look at aspects of the visual environment usually taken for granted with a new level of attention and understanding. See, for instance, the Metromix Chicago review (2007).

26. I have personal experience of this classification problem. See Rick Poynor, Obey the Giant: Life in the Image World (Basel: Birkhäuser, 2007) and Designing Pornotopia: Travels in Visual Culture (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2006).

27. See Martin Jay, “That Visual Turn: The Advent of Visual Culture,” Journal of Visual Culture 1:1 (2002): 87-92.

28. Mirzoeff, The Visual Culture Reader, 6.

29. Nicholas Mirzoeff, An Introduction to Visual Culture (London and New York: Routledge, 1999): 6. See also the substantially revised second edition, 2009.

30. Guy Julier, “From Visual Culture to Design Culture,” Design Issues 22:1 (2006): 76.

31. Mirzoeff, An Introduction to Visual Culture (1999), 3.

32. Ibid, 7.

33. Irit Rogoff, “Studying Visual Culture” in The Visual Culture Reader, 27.

34. Dikovitskaya, Visual Culture: The Study of the Visual after the Cultural Turn, 4.

35. Roxane Jubert, Typography and Graphic Design: From Antiquity to the Present (Paris: Flammarion, English ed. 2006), Stephen J. Eskilson, Graphic Design: A New History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), Johanna Drucker and Emily McVarish, Graphic Design History: A Critical Guide (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2008) and Patrick Cramsie, The Story of Graphic Design (New York: Abrams, 2010). For extended discussion of Eskilson, see Alice Twemlow and Lorraine Wild, “A New Graphic Design History?” Design Observer (2007). For extended discussion of Drucker and McVarish, see Denise Gonzales Crisp and Rick Poynor, “A Critical View of Graphic Design History,” Design Observer (2008).

36. See Jonathan Harris, The New Art History: A Critical Introduction (London and New York: Routledge, 2001).

37. See Andrew Blauvelt, “Modernism in the Fly-Over Zone,” Design Observer (2007).

38. Gayatri Spivak quoted by Rogoff, The Visual Culture Reader, 26.

39. Rogoff, The Visual Culture Reader, 33.

40. For further reflections on this oversight, see Johanna Drucker, “Who’s Afraid of Visual Culture,” Art Journal 58:4 (1999): 36-47.

41. Mirzoeff (interview) in Visual Culture: The Study of the Visual after the Cultural Turn, 232.

42. Mirzoeff, An Introduction to Visual Culture (1999), 14.

43. Mitchell (interview) in Visual Culture: The Study of the Visual after the Cultural Turn, 256.

44. Mitchell, The Visual Culture Reader, 90.

45. See Mirzoeff and Mitchell in Visual Culture: The Study of the Visual after the Cultural Turn, 227-31, 243, 255-7.

46. Exceptions should be noted, in particular the work of Ellen Lupton, curator since 1992 of exhibitions about graphic design for the public at the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum. Lupton’s practice as designer, educator, curator and writer provides a paradigm for a more publicly oriented presentation of graphic design. As design director of the Walker Art Center, Andrew Blauvelt also assumed a curatorial role. In 2010, he was appointed chief of communications and audience engagement at the center.

47. See “Visual Culture Questionnaire,” October 77 (1996): 25-70. In particular, see Thomas Crow: 36.