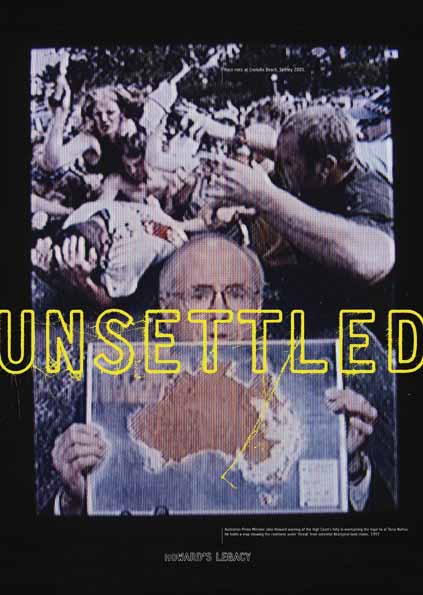

Engaged design: poster by Brisbane-based Inkahoots, 2007, a tribute to Redback Graphix

For more on Inkahoots see Change Observer

This week, in a review in the Observer newspaper about the proposed design of the London HQ for the Swiss bank UBS, the British architecture critic Rowan Moore set out the demands of principled design with startling clarity. Here are the opening words of his article:

Good architects should be able to walk and chew gum at the same time. That is, meet their clients’ needs, design well-made and sustainable buildings, and also add something to their building’s setting, such as work with their surroundings to create a place more harmonious/fascinating/humane/pleasurable than it was before.

The particulars of this project don’t concern me here, though I’m inclined to agree that the building designed by Make looks like it will be “an aloof fortress that ignores its responsibilities to the wider community.” Moore’s statement of principle caught my eye because I was already mulling over these issues with reference to my recent Observatory essay about the state of Dutch graphic design.

Just as the comments thread appeared to be running out of steam and the essay was about to drop off the front page, Florian Pfeffer, a German professor of graphic design with a commercial practice in Amsterdam, Berlin and Bremen, arrived with a thoughtful riposte to a number of points I had made (or at least that he thought I had made). I had been wondering how to reply to his comments, when I read Moore’s article, which addressed the two interlinked issues on my mind. First, the question of the designer’s relation to the client. And second, what it means to function as a designer (or architect) attempting to apply clear and conscious principles — in other words, a position — to projects undertaken for clients.

I can’t resist adding that we in design seem to have been talking about these matters forever. It’s amazing that the issues at stake apparently remain so unclear to so many designers, and that there is always someone ready to say, “Oh, it’s so much more complicated now than it used to be” — with the implication that earlier analysis (and perhaps wisdom) can safely be ignored. Often this assertion is made about a time before the designer was even working. How do they know?

Moore mentions the high regard in which UBS’s architects are held in some quarters:

Clients of Make praise the company as responsive and professional, and these virtues are obviously important ones. What is lacking is a core of principles: a Make building tends to be as good as its brief . . . If UBS wants a defensive-aggressive citadel, it gets it.

This, then, is the fundamental issue: core principles. Of course, a design company can dedicate itself to fulfilling its clients’ needs and leave it at that. This has always been a possibility. But it’s perfectly fair for the rest of us to ask: is that all there is? When the issue of guiding principles comes up, even allowing for the contingencies of our own time, it simply isn’t adequate for designers to suggest that the luxury of resistance might have been possible in the past, but that everything is far too fragmented and complicated to allow this now. If you can’t be the designer you would like to be in the work situation you are in, then follow the example of highly principled designers — they still exist — and change your situation. The issue then becomes, as Moore rightly suggests: what else can a designer add to a project beyond merely fulfilling the client’s brief?

Nor should it ever be a question of attempting to “bend clients” to one’s will, and I would like to be clear that, though I used this phrase ironically in my essay to evoke the mystery of Dutch design when seen from afar, I have never advocated such arrogant and most likely counterproductive tactics. I have been a client of designers many times myself and if anyone were to try this approach with me, I would have no wish to work with them. I do, however, respect the validity and indeed necessity of a designer’s principles and personal position and hope to work with designers where there is a creative correspondence of views. Isn’t this the most that anyone who is sensitive to design, on either side of the meeting-room table, can wish for?

Moore rounds off his critique of Make’s bank HQ design with this sharp summation:

Make is a perfect distillation of 00s architecture, where genuine professionalism, slick stylishness, and a real if well-advertised commitment to the environment are boosted by hype and infinite adaptability to the demands of the market.

Exactly the same could be said about the kind of graphic design I was criticising in my essay. This is part of a larger cultural tendency, for sure, but can that be a reason — is it ever a reason? — to suggest that we just go along with things as they are? Let’s discard the complacent mid-1990s to mid-00s mindset once and for all. These difficult times demand principled engagement with complex societal needs, not bland acquiescence to the marketplace.