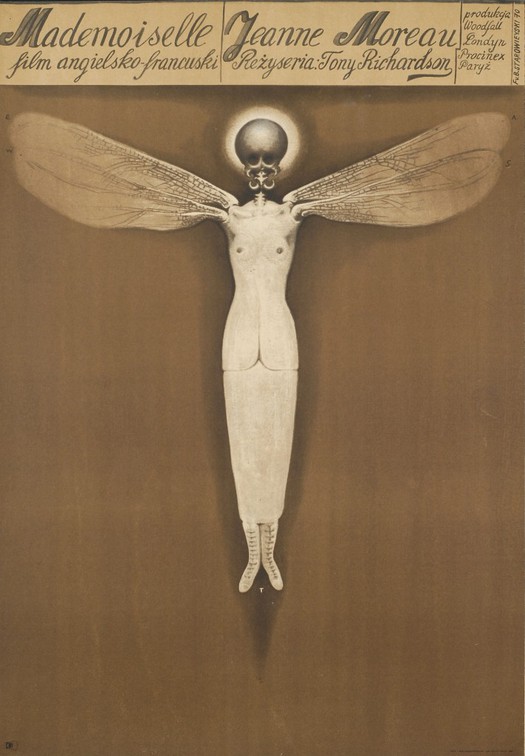

Franciszek Starowieyski, Mademoiselle, film poster, Poland, 1970

It’s not my intention for this blog to become poster central, but with all eyes on the Wim Crouwel exhibition in London at the moment, it would be easy to overlook two small exhibitions in the city of posters by Franciszek Starowieyski. The Polish artist and designer (1930-2009) is of great interest to me — his work both attracts and repels — and I included some of his more surreal posters in my exhibition Uncanny last year. Produced in the 1960s and 1970s at the same time as Crouwel’s posters, Starowieyski’s best work occupies a polar extreme. If Crouwel is the model of an Apollonian designer, then Starowieyski is violently Dionysiac. It would take a singularly catholic taste to embrace both bodies of work with equal enthusiasm.

The Starowieyski exhibitions are part of Kinoteka, the ninth Polish film festival. One runs at the Riverside Studios in London until 10 April and the other is in the mezzanine at the Barbican Centre from 7 to 13 April. The exhibitions’ curator, Jacek Szelegejd, notes that, despite the impact made by the flamboyantly extrovert artist in Poland, and not forgetting an exhibition at MoMA in 1985, he remains, in a deeper sense, “unknown and undiscovered.” Welcome as they are, these exhibitions are not going to rectify that. The Riverside display consists of just 17 posters along the back wall of the building’s bar. They look magnificent, but they don’t have labels and are relegated to the status of eccentric décor, a colorful backdrop for socializing and drinking. I’m hoping the Barbican show will aim higher, though it sounds like that display, too, will be placed in a thoroughfare.

Franciszek Starowieyski, Fanfare, film poster, Poland, 1960

Szelegejd’s selection prioritizes the earlier posters, and this is as it should be. An artist-approved monograph published in 1999 shows very few posters from the late 1950s and early to mid-1960s, concentrating instead on Starowieyski’s later large-scale art and live Theater of Drawing sessions, where he produced florid, fantastical images of generously proportioned nude models, who cooperated gamely with the vigorously masculine maître. It was a kind of Action Surrealism, but even to a sympathizer these images could be too much.

Early Starowieyski is another matter. The achievements of the Polish poster school are no secret and Starowieyski was one of the finest exponents. There are just enough of the less frequently seen posters from the start of his career on show to reveal how, to become an artist, he found it necessary to abandon graphic devices he had used with great fluency as a designer. In a poster from 1956, for instance, he inserts a painted image of a woman’s face into the outline of a stag; the background is a flat field of purple and he forms the sun from Matisse-like, cut-out fragments. It’s a charming and highly effective design, but there is no hint of any psychotherapeutic drama and it doesn’t look anything like what we now think of as a “Starowieyksi”: a graphic universe in which desire, sexuality, monstrosity, madness and death conjoin in some of the most unbridled and grotesquely excessive images ever to grace — some might say abuse — the poster as a medium. (There are many examples to discover here, here and here.)

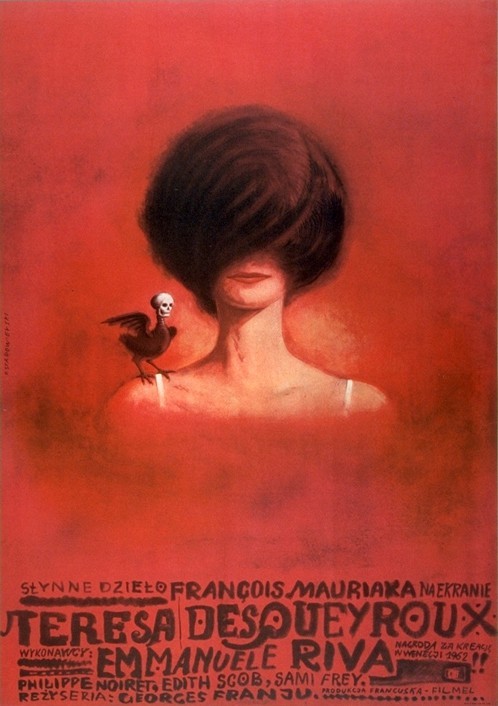

Franciszek Starowieyski, Teresa Desqueyroux, film poster, Poland, 1964

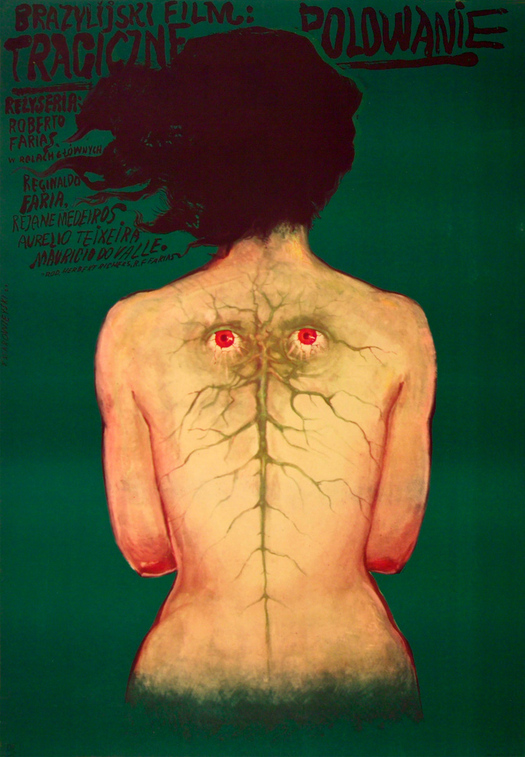

Franciszek Starowieyski, Tragiczne polowanie, film poster, Poland, 1967

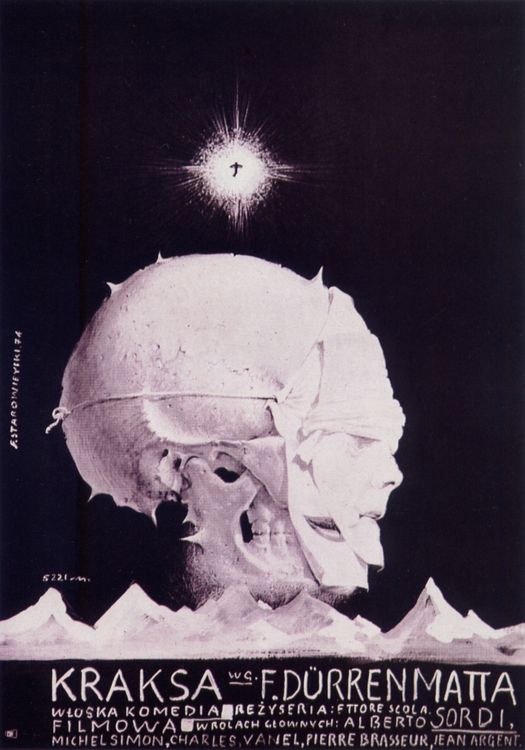

By 1960, when Starowieyski transplants a cow’s head with a cross between a tuba and a French horn, his commitment to surrealistic chance encounter and the disturbance of the irrational image is already becoming clear. The other posters from the two exhibitions that I am showing here come from a mid-point in Starowieyksi’s development when his imagery was painterly and personal, with recurrent visual themes, while still retaining a high degree of graphic control over the image. His picture-making hadn’t yet become stylized, or lapsed into repetition and baroque self-parody, which happened later, after the period covered by Szelegejd’s shows. Rough-hewn typography was soon replaced by painted lettering, but Starowieyski still took care at this stage to fit the words to the image, as with Tragiczne polowanie (1967), where they flow into the woman’s mass of black hair. Later, he would exile the title and credits to a narrow band at the top or bottom (as in Kraksa, 1974), as though they were a distraction from the painted image that had long ago become his overriding concern.

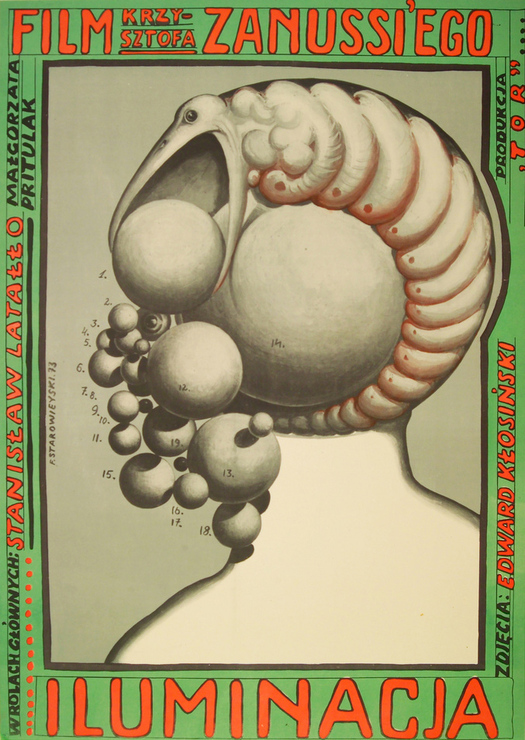

Franciszek Starowieyski, Iluminacja, film poster, Poland, 1973

While many of these bizarre images still pulse with psychic energy and viewers are free to extract whatever meanings they please, the designs call out for a contextual elucidation they have rarely, and certainly not recently, received in English-language writing on the subject. In poster collector Krzysztof Dydo’s Polish Film Poster, published in 1996 and now hard to find, Jaroslaw Wojciechowski discusses Starowieyski’s Iluminacja (Illumination) poster. The film tells the story of a student of physics who becomes a university researcher and struggles, in the course of the narrative, to understand the nature of human existence. “The protagonist’s consciousness is presented in the form of a stylized monster which devours balls marked with numbers, each of them of different size,” writes Wojciechowski. “They symbolize succeeding events — stages in the hero’s life. The twisted monster forms, at the same time, an outline of [the] head of a figure which seems to be covered with the fragments of food which haven’t been devoured yet.”

Starowieyski’s posters were at their most original when they reconciled his psychological obsessions with the themes of the films he interpreted, and with the need to produce a scintillating graphic image that fully exploited the urgency of an ephemeral medium that has long ago established it can sometimes, in the right hands, become lasting art.

Franciszek Starowieyski, Kraksa, film poster, Poland, 1974