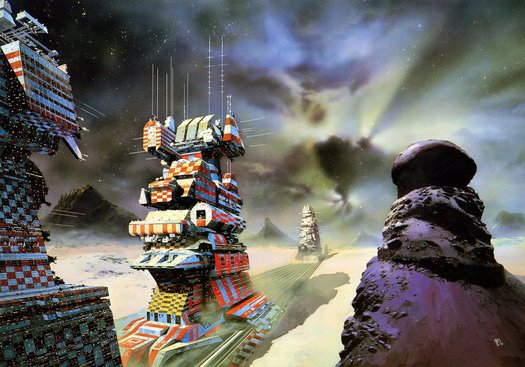

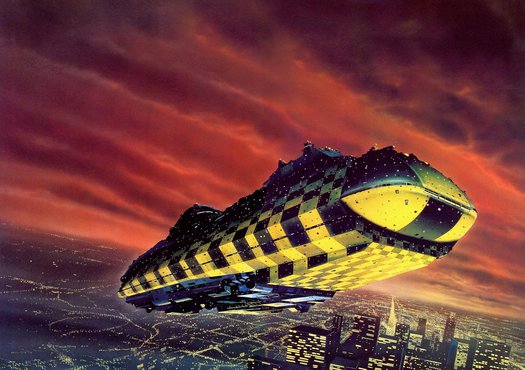

Chris Foss, Travelling Cities, Esquire and Sunday Times Magazine, 1981

Science fiction artist Chris Foss’s new monograph is an amazingly obsessive piece of cataloguing. At first it seems almost too relentless, with every painting precision welded into the grid, all the pictures equidistant, and no room to breathe. The career survey works systematically through the artist’s perennial themes: soaring spaceships, vast land-cruisers, outlandish architecture, gravity-defying cities and installations floating on huge rocks, giant robots on the rampage, and colossal metal claws emerging from the deep to snatch unwary flying vehicles. The title, Hardware, gets it exactly right. Rian Hughes’s exhaustive selection of images feels more like a product catalogue aimed at someone shopping for a space-cruiser than a standard-issue art book.

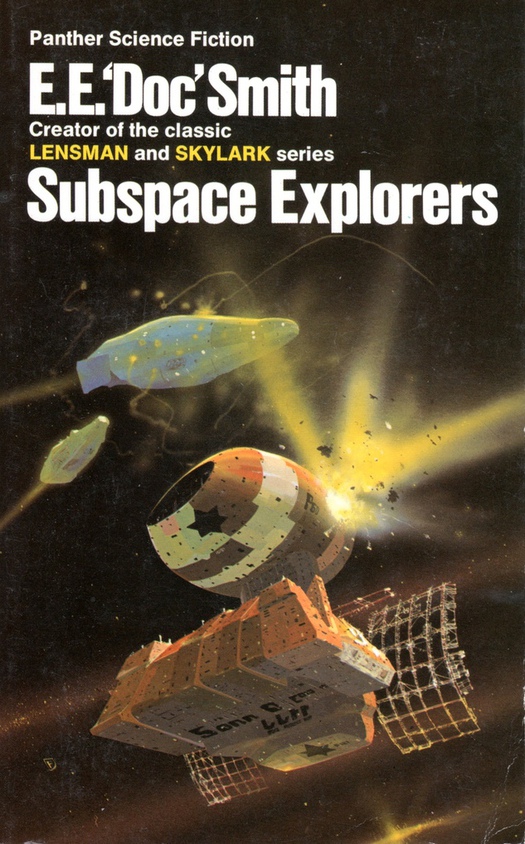

Chris Foss, Subspace Explorers, Panther, 1977

In the 1970s and 1980s, when Foss became a cult figure among SF fans, he would produce two or three book covers a week, mostly for space fiction by writers like Isaac Asimov, James Blish, E.E. “Doc” Smith and A.E. van Vogt. In my time, I have read a fair number of these space operas, though not since I was 12 or 13.

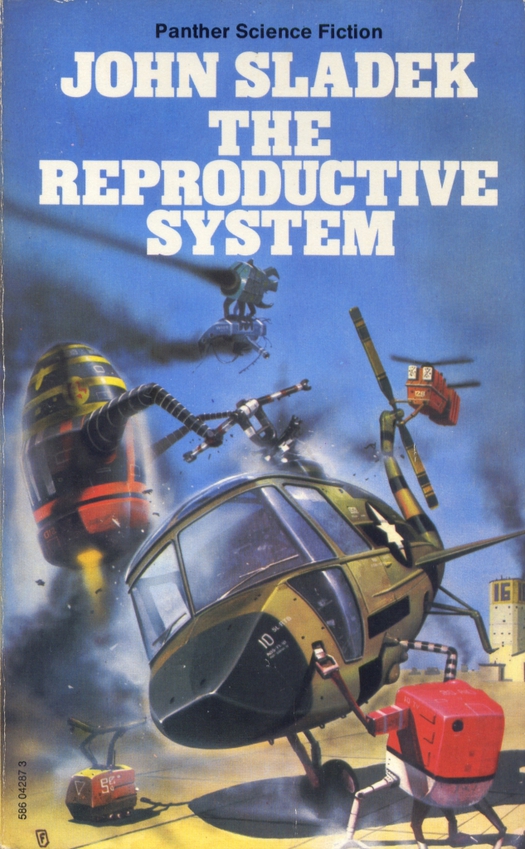

Chris Foss, The Reproductive System, Panther, 1977

It was science fiction’s speculative 1960s new wave that appealed to me, and Foss produced a sardonically witty cover, which I still have, for John Sladek’s The Reproductive System, a satire about self-reproducing machines taking over, as well as four covers for J.G. Ballard, the new wave’s most emblematic figure. The first of these is Foss’s smoking, sulphurous cover for Crash (1975), which Ballard heartily disliked. Foss had form when it came to sex, as illustrator of the famous The Joy of Sex (1972), but he was disgusted by Crash and threw it across the room, according to Hughes.

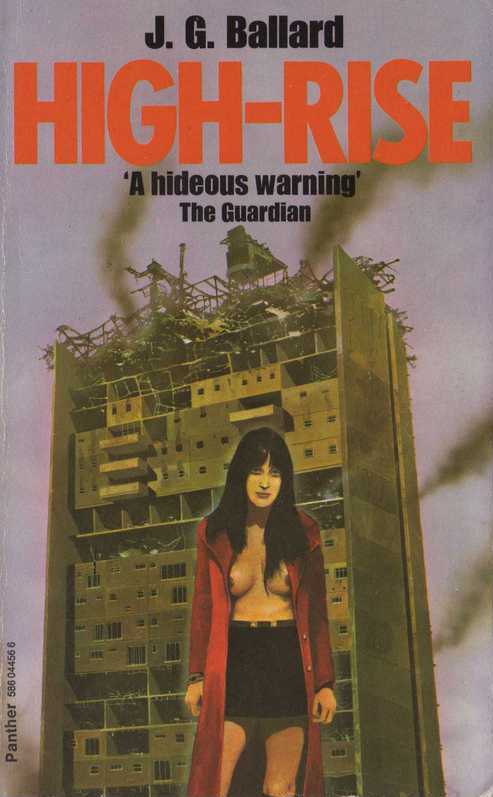

Chris Foss, High-Rise, Panther, 1977

Rather better is Foss’s brooding, dystopian interpretation of High-Rise (1977), one of Ballard’s most powerful novels, and his cover for The Drought, the same year, is also fine — the hulking, beached ship is a natural subject for Foss. With Low-Flying Aircraft (1978), he did his standard hardware routine and delivered a hurtling space shuttle (or something) that looks like it is about to burn to a crisp. Foss is famous for not reading the books.

On the whole, though, that was never a problem — for the publishers, for the readers, or even, it would seem, for most authors. Foss believes they simply didn’t care what he put on their books. In a post about science fiction artist Richard Powers, I proposed him as a kind of auteur of the book cover, using the medium as a platform for the work he wanted to do. This is what Foss did, too. He can be bullish about the relationship between fine art and the jobbing artist. “The real talent is in commercial art,” he says. “Fine art is just hot air.” On the other hand, he notes that, “It never occurred to me that the paintings had any intrinsic value.” The aim was always to produce the final printed work rather than a unique object for exhibition and sale. Consequently, many of his early pictures have been lost; often he just left them with the client (a common fate of illustrations) and some of the images had to be scanned for Hardware from transparencies or book covers. Presumably this is one reason why no sizes are given, a real loss when it comes to taking the full measure of these paintings as art. We need an exhibition of those that remain.

Chris Foss, In Our Hands, The Stars by Harry Harrison, Arrow, 1986

Chris Foss, The Bloodstar Conspiracy by Stephen Goldin and E. E. “Doc” Smith, Panther, 1978

That is, after all, what the book invites us to do. As it happens, Foss provides a particularly interesting case study in the when-is-illustration-art debate because, in 1995, he was the target of an unseemly, Roy Lichtenstein-like act of appropriation by the British artist Glenn Brown. Brown’s painting The Pornography of Death (Painting for Ian Curtis) After Chris Foss (1995) was an exact copy, with nothing added, of Travelling Cities (1981) by Foss, which had appeared in Esquire and the Sunday Times Magazine. Brown’s painting showed up again in 2010 in, of all places, the Crash: Homage to J.G. Ballard exhibition at the Gagosian Gallery in London.

The laughable art-world delusion that Brown’s transcription was somehow art while the Foss original wasn’t seemed to boil down — yes, really — to size. Brown’s work was bigger. But, as I argued recently, the real determinant here is context: if you can get an art gallery to show something as art, then to all intents and purposes, and so far as the gallery, critics, art magazines and press are concerned, it is art. The other contextual shift that Brown worked along the way was to graft on a somewhat spurious though undeniably provocative title that roped in both the dead singer of one of the great cult rock bands and the then very fashionable specter of porn (even Hardware acknowledges that Foss creates a kind of techno porn). I have a lot of sympathy for the argument that Hughes made in Eye, in 2001, about the outrageous injustice of this and similar episodes. The truth is simply that Brown had a plausible art-world shtick, while Foss never made any attempt to position himself as an art-world approved Artist, which doesn’t mean his pictures cannot be seen as art.

Chris Foss, Earth is Room Enough by Isaac Asimov, Panther, 1986

Chris Foss, Midsummer Century by James Blish, Arrow, 1975

Foss’s work is uneven, though that isn’t surprising given the speed of its production. The scenes he paints are intrinsically improbable, and for many viewers inherently ridiculous, so one way to measure their success as paintings is to see whether they contain something that is in some way believable, and this comes down to the quality of what we might call their pictorial rhetoric. Foss’s awkward-looking monsters, ambulating war machines with giant pincers, and even his lumbering, pre-Transformers robots, might have fulfilled their original purpose as generators of reader excitement, but looked at now, as standalone images stripped of their titles and type, they often don’t convince. Other machines are so bizarrely conceived — a combine harvester the size of a fortress — and unlikely as any kind of humanoid industrial design, no matter how well Foss paints them, that they can only be viewed as amusing curiosities today. The prevailing sensation in these paintings of awesome power contained, unleashed, or out of control (Foss loves rockets) is close to the unbridled power fantasies, furious clashes, constant explosions and radiating energy lines in superhero comic books. The paintings need to reach a deeper level of perception and experience to become art.

Chris Foss, Second Stage Lensman by E. E. “Doc” Smith, Panther, 1973

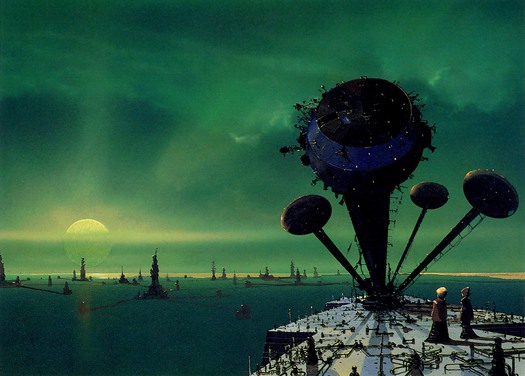

In the seven paintings I show here, something else is going on. These visionary images have a stillness, a control of atmosphere and a mood of mystery and wonder, even when something huge, alien, imponderable and beyond our terrestrial grasp is taking place. Foss loves the paintings of J.M.W. Turner and his finest pictures, often from the 1970s, seem as much concerned with ambience and painterly effect — they are cosmic cousins of Turner’s Rain, Steam and Speed, at least in spirit — as with the engineering of the vast structures they depict. They are also early visual encapsulations of what came to be known in the 1990s as the technological sublime. The vertiginous sense of awe, wonder, poetry and terror that people experienced in nature, when opening their senses to the sky, mountains, forests, rivers or oceans, could now be felt when contemplating the frightening immensity of a machine’s harnessed power, the magical effectiveness of electricity, or the boundless matrix of digital connection.

Foss positions us over the abyss, as viewers, like Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, except that we are taking in the unknowable bulk of a miraculous machine for traversing space, bulging like a ripe, colorful fruit that has tumbled from the heavens. Or gazing at the eerie green twilight from the deck of a monitoring station on an unfathomably distant world.

Chris Foss, The Overman Culture by Edmund Cooper, Coronet, 1974

See also:

Unearthly Powers: Surrealism and SF

Speculative Fiction, Speculative Design

Everything has Become Science Fiction