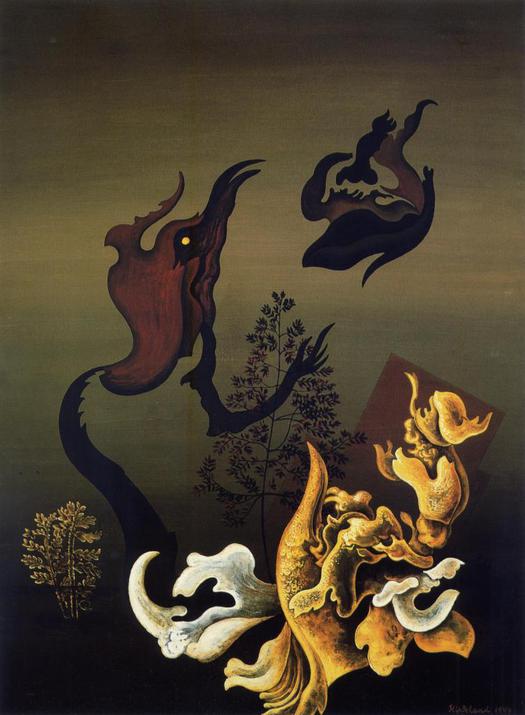

Vance Kirkland, Antipodean Garden, casein on wood, 1949. Kirkland Museum of Fine & Decorative Art

A couple of weeks ago, in the Denver Museum of Art, I walked into a room full of marvelous paintings by an artist who was unknown to me. I had seen two or three similar pictures by him before, though I had never taken in the painter’s name, Vance Kirkland. The paintings, on view in a section titled “Earth and Fire,” belonged to different phases in the Colorado artist’s career. I was particularly drawn to Kirkland’s landscapes from the 1940s showing Surrealist influences — that won’t surprise regular readers of this blog — but his later works, swirling stellar abstracts that send you plunging into a moment of cosmic eruption or creation, were also stunning. I made a mental note to find out more about Kirkland later.

The next day I was wandering in the city when I noticed on a map that there was a Kirkland Museum of Fine & Decorative Art. How many significant artists called Kirkland could there be in Denver? It was mid-afternoon and it was my last chance before leaving Denver in the morning so I hot footed it over to Pearl Street, where the museum is located, hoping that this would prove to be the Kirkland mother lode.

The Kirkland Museum of Fine & Decorative Art, Denver. The original building, on the right, was constructed in 1910

I liked the odd-looking building the moment I saw it. The blank expanses of brick with hardly any windows gave no clue as to the style of museum housed within. At this point our story reaches a forking path because the Kirkland Museum, as I found on entering, is three museums in one. It does indeed contain a fantastic collection of paintings by Vance Kirkland (1904-1981), whose studio this used to be; the building has since been extended. The museum also displays a 100-year survey of art from Colorado with an emphasis on modernism. These sections alone would be rewarding enough, but the building has so much more — a collection of 3,300 pieces of modernist decorative art and design. And all this is packed almost haphazardly, without the usual curatorial divisions, into a series of modestly sized domestic rooms, as though you are walking around a private house admiring the owner’s treasures (actually you are). The place is overwhelming, one of the most delightful museums I have seen anywhere. If you have no interest in painting, the design collection alone is a pressing reason to visit, and one day I hope to return to Denver to take a longer look at all these objects.

Painting by Vance Kirkland displayed among the museum's decorative art collection

The museum was almost empty and I fell into conversation with one of the staff who took me on a little tour when I told her I had come to see the Kirklands. She showed me the straps hanging above Kirkland’s workroom table in which the 5-foot 2-inch artist would lie working on the painting below. “There is no up or down in space,” Kirkland said, “and this is as close as I’ll ever get to being an astronaut.” The device was supposed to protect his back, but it looked awkward and uncomfortable. My guide mentioned that the director would return soon. When he arrived, he said his name was Hugh Grant — he sometimes wears a cape, I learned later, and cuts quite a figure around Denver — and he offered to show me other paintings by Kirkland in his office, where he drew to my attention a particularly brilliant picture that mixed oils and watercolor in impossibly complex translucent layers: Kirkland was a master of painterly technique. Grant was Kirkland’s friend and inherited his estate; the artist’s art and design collection became the foundations for the extraordinary collection Grant has built. He has written extensively about Kirkland and organized many posthumous shows of his work.

Vance Kirkland, Woden’s Ring, watercolor and gouache, 1945. Kirkland Museum

Vance Kirkland, Martian Dance, watercolor, gouache and denatured alcohol, 1952. Kirkland Museum

Grant divides Kirkland’s paintings into five phases: designed realism (1926-44); Surrealism (1939-54); hard edge abstraction (1947-57); abstract expressionism (1950-64); and dot paintings (1963-81). While the style evolved, the artist’s concerns remained essentially the same. He was fascinated by moments of origin and creation and in the surrealistic paintings — with titles like Six Million Years Ago and Ten Million Years Ago — the landscape appears to live and writhe with primordial energy while tiny human figures and other creatures find shelter in colossal twisting branches and root systems. In the early 1950s, Kirkland exhibited in New York with Max Ernst. From around 1960, his pictures of “mysteries,” as he sometimes called them, suggest a highly sophisticated form of abstract science-fiction art, with boiling gases and drifting clouds of vapor, although they were never used, as they might have been, on book covers. Kirkland’s later pictures are tumultuous Big Bangs and shooting supernovas of vibrant color painstakingly rendered, as he hung from the ceiling in his straps, with thousands of little dots. Here, too, he draws attention to his obsession with titles such as Explosions on a Sun 100 Billion Light Years from Earth. These were much less well received, but Kirkland continued to paint them for his own pleasure.

I asked Grant whether Kirkland read science fiction. He said not, but the painter was certainly preoccupied with science and read books about the subject. “But he was not really concerned whether science proves or refutes his paintings,” writes Grant. “He was merely using outer space as a vehicle for his imagination, and was stimulated by the vastness of space and time, and the energy that exists there. It would only be a coincidence, like Jules Verne’s fiction, if something was substantiated in Kirkland’s paintings. [. . .] The more one looks at the paintings, the less important a relation to science becomes, because they stand on their own as examples of an artist’s unique imagination and as original abstract canvases.”

Vance Kirkland, The Energy of Explosions 20 Billion Years B.C, oil, water and gold on linen, 1978. Kirkland Museum

Denver has some excellent art attractions. The Denver Art Museum, extended a few years ago by Daniel Libeskind, is terrific. MCA Denver, the museum of contemporary art designed by David Adjaye, has to be on any art lover’s route. But if I had to pick just one Denver museum to revisit it would be the Kirkland because the overloaded displays have a fecundity and sense of wonder that a white cube (or in Libeskind’s case, trapezoid) can never match, and as a setting for Kirkland’s art this profusion works perfectly. This week I flipped through 50 American Artists You Should Know, a recent survey, on the off-chance that Kirkland had made the cut. Of course, he hadn’t and it’s the fate of many highly accomplished artists, especially those who choose to live and work in the regions and ignore the fashions of the art scene, to be overlooked by art’s metropolitan powerbrokers and tastemakers. But maybe it’s better that way. When you stumble across something previously unknown and unexpected, it can explode in your mind’s eye with scintillating power.

This is the second post in an occasional series titled “On Display” about unusual museums.

See also:

Lost Inside the Collector’s Cabinet