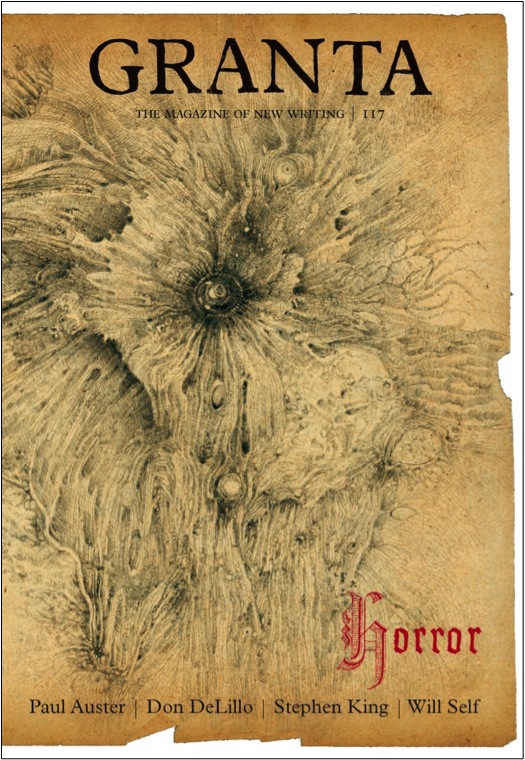

Granta no. 117, Fall 2011. Cover art by Jake and Dinos Chapman. Artistic direction by Michael Salu

The new issue of Granta has a rather fine cover by the British artists Jake and Dinos Chapman. The literary magazine’s theme is horror and the Chapmans’ delicate pencil drawing on fragile 18th-century parchment, which twists around the spine on to the back cover, shows something nameless, formless and unspeakable. The image looks organic but ancient, with the texture of diseased bark or some sentient, pestilential space fungus. In places, the teeming clumps and flows converge on an aperture, or separate to reveal bulging convexities that could be eyes. There is something unmistakably genital about these contours and openings.

It’s a vision of ineluctable, Lovecraftian horror and the Chapmans have supplied a short text about the cover, printed at the back and composed in the morbid, hysterically overblown and addictively hypnotic style perfected by H.P. Lovecraft. The putative narrator sits at his desk in the light of the “gibbous moon” and begins to draw:

Yet, as ever, my attempts are mocked by the monstrosities that leer up at me from the page, wrenching me from my reverie, leaving me able only to stare aghast at the horrors that materialize and multiply before my eyes, seeping unbidden, crowding at the edges of my vision as if from a foul universe beyond the very fibres of the parchment, drawn forth by the frenzied scuttling dance of my accursed hand across the sheet, in its insane labour to describe and catalogue its most vile, degenerate subjects.

By the end of the page-long narrative, you get the impression the Chapmans are talking metaphorically about themselves while also giggling at the reader behind their hands: they cannot explain these vile graphic emanations, they do not claim them as their own, they are helpless to stop them, and they have no idea when their loathsome task will be finished.

Jake and Dinos Chapman, painting from the series One Day You Will No Longer Be Loved, 2008

Commissioned by artistic director Michael Salu, the Chapmans were an inspired choice for the cover. Few artists have ever embraced the ambivalence of horror with more relish. In Hell (1999-2000), thousands of little plastic models of Nazis were slaughtered by merciless mutants in an orgy of bloodletting displayed like a model train set in nine glass cases arranged in the shape of a swastika. I wrote about Hell, which was later destroyed in a fire, in my book Obey the Giant, and I still regard it as one of the most extraordinary art works to come out of Britain in the past 20 years. The piece, since remade as Fucking Hell (2008), mind-gamed viewers with an insoluble challenge. How are you supposed to process a work that seduces you into lingering over the spectacle of apocalyptic violence and degradation — and linger we did — while denying the viewer any possibility of redemption? What bleak and intractable secret do we learn about ourselves here? The Chapmans described Hell as “the aesthetic version of a black hole. It appears extremely intense yet it is completely inert.”

A few years ago, the brothers announced they intended to make a horror film, though nothing appears to have come of the plan so far. Horror films, they revealed, especially the so-called video nasties that caused a moral panic in early 1980s Britain, had made a big impact on them when they were growing up, “They coloured a lot of people's experience,” said Dinos. “A lot of 1970s horror films had a nihilistic and bleak outlook on life compared with contemporary ones. They didn't portray a world of hope.” The connections between their work and the horror film are so obvious that it’s strangely negligent of art critics not to have made a lot more of this.

In 2007, the film critic Mark Kermode, an aficionado of horror, interviewed the Chapmans on British TV and illustrated his points with clips from Paul Morrissey’s Flesh for Frankenstein (1973), Zombie Lake (1981) in which ludicrous Nazi zombies emerge from the noxious green depths, and Brian Yuzna’s Society (1992), which culminates in an outrageous spectacle of sticky, polymorphous, bodily fusion. This certainly made a change from the usual overwrought catalogue essay references to Freud and Bataille. “It’s odd how any kind of historical overview of our work has neglected to mention how immersed we are in the culture of the video nasty, which was a substantial portion of our entrance into adult thinking,” Jake agreed. Kermode, a publicly professed Christian and admirer of The Exorcist who knows his Lucio Fulci from his Mario Bava, seemed to need to find something of redeeming value, some reassuringly humanist glimmer of light, in even the blackest, goriest and least excusable horror films. Jake Chapman, becoming irritated, dismissed the vitiating presence of any such cuddly sentiment in their own work. “There are razor blades in it, you know. Really.”

By comparison with some of their more bloodthirsty horror-shows often derived from Goya, the Granta cover is teasingly understated as a representation of sublime horror, though no easier to calibrate or reduce. It can be seen as an image of what Eugene Thacker, writing in In the Dust of This Planet: Horror of Philosophy vol. 1, calls the horror of the “world-without-us” — a planet both “spectral and speculative,” “impersonal and indifferent,” from which the human has been subtracted (“a foul universe beyond the very fibres of the parchment”).

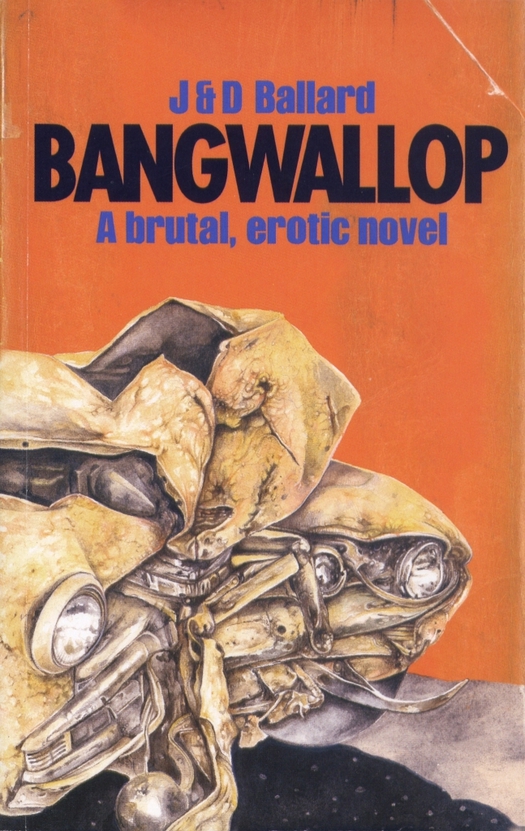

Jake and Dinos Chapman, cover image for novel, self-published, 2010

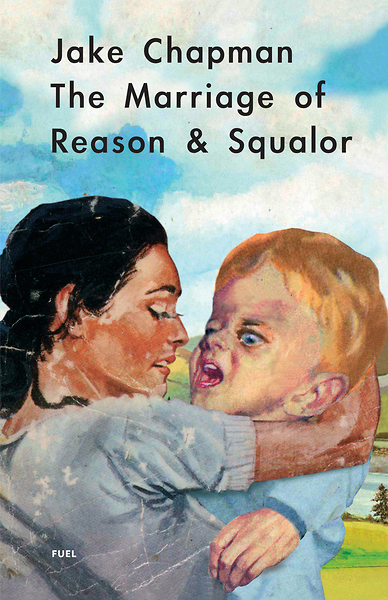

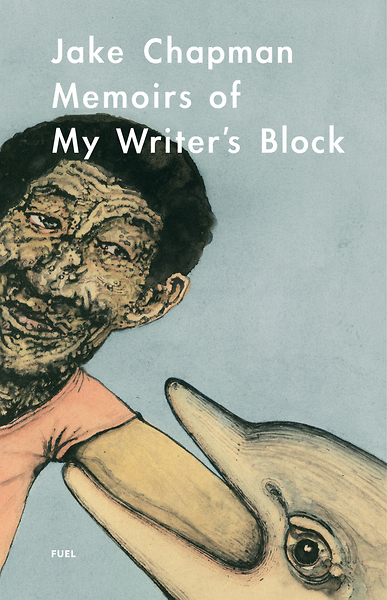

It probably isn’t something they care about much, but the Chapmans are good at cover images. Last year, for the J.G. Ballard exhibition at the Gagosian Gallery in London, they produced their own “crashed” version of Ballard’s cult novel Crash and gave Chris Foss’s famous cover illustration a new chassis in the process: the body of the mangled car now appears to be corroded by a metal-eating infestation. Like the Chapmans’ unnameable outgrowth for the Granta cover, it seems to fold back in on itself in some gross act of self-ingestion. The covers of The Marriage of Reason & Squalor and Jake Chapman’s other two novels, published by Fuel, bristle with the same sense of violated decorum and unease.

Hour upon unremitting hour, hostage to the unsolicited action of my traitorous hand. A vast lexicon of filth spreading seamlessly across innumerable sheets . . .

Jake Chapman, cover image for novel, Fuel Publishing, 2008

Jake Chapman, cover image for novel, Fuel Publishing, 2010