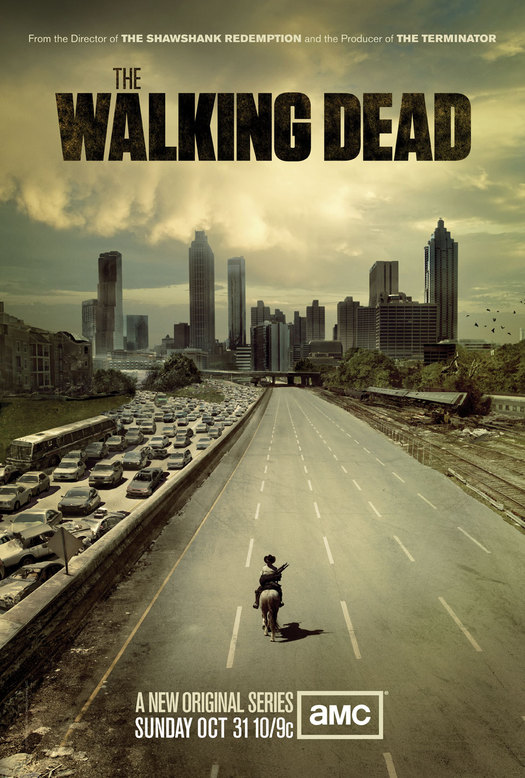

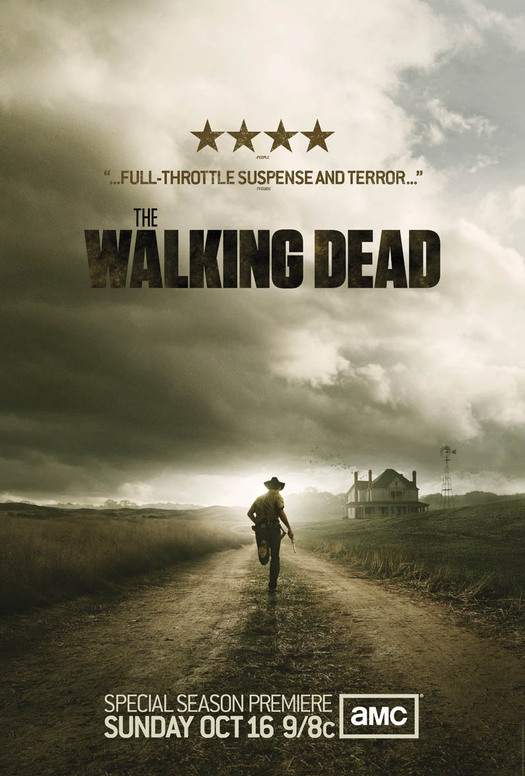

The Walking Dead, television series developed by Frank Darabont, 2010

Are the tasteful precincts of Design Observer, where most writers’ thoughts usually run to saving the planet, the place to admit to an interest in zombie films? Perhaps we can see these grotesque fantasies of a world on the brink of collapse as the dark, unmentionable flipside of the same philanthropic coin. And unless you are unusually resistant to the virus, there’s a good chance that you have watched a few zombie movies. Zombies have been mainstream for the past decade. Who could have predicted 20 years ago that something called The Walking Dead, a TV series about survival after the zombie apocalypse — as we affectionately term it now — would become such a hit? Or, for that matter, be so good?

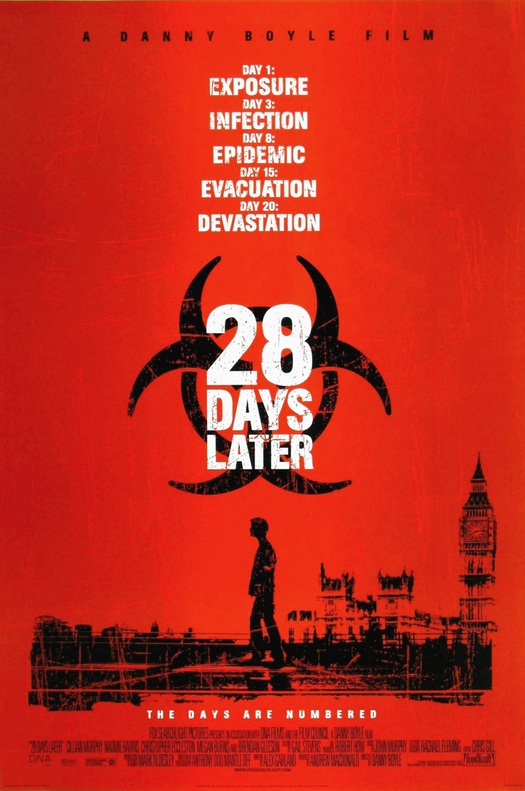

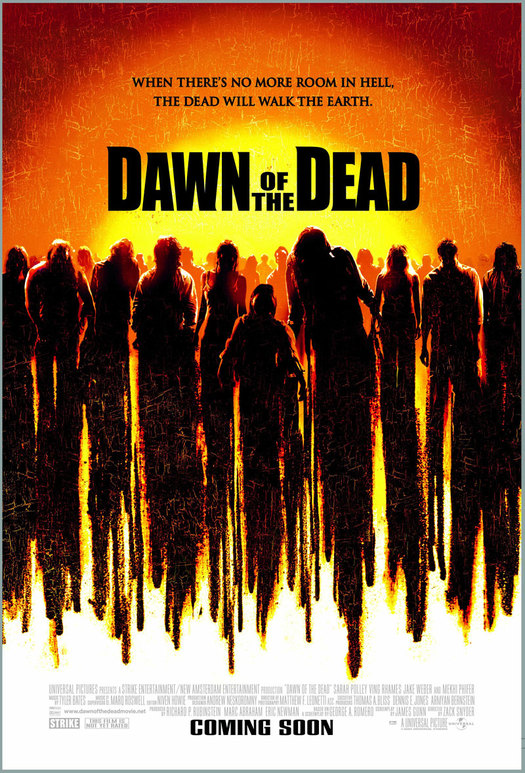

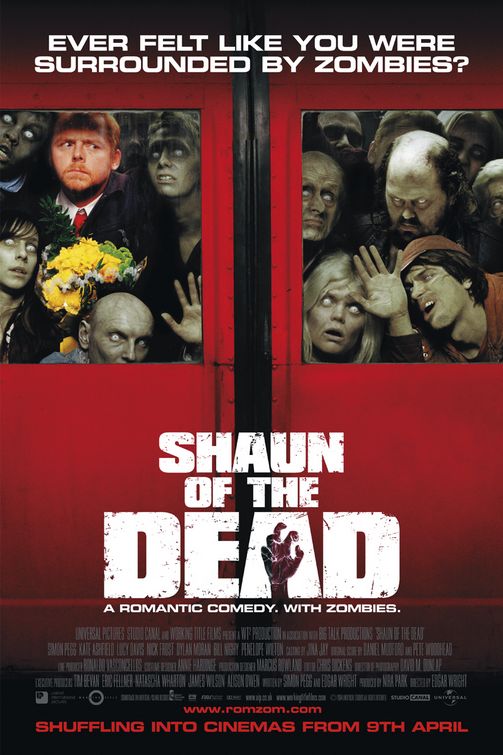

The shuffling, flesh-eating American zombie, as opposed to the earlier Haitian voodoo version, arrived with George Romero’s once notorious Night of the Living Dead (1968). Since then, there have been hundreds of cheapo zombie films, and with a few honorable exceptions, such as Romero’s satirical Dawn of the Dead (1978) set in a mall outside Philadelphia, only an unreconstructed gorehound would bother with most of them. The latest zombie infestation probably began with 28 Days Later (2002), the film where zombies ushered in a new era of terror by being able to run. The Dawn of the Dead remake two years later might have seem ill-advised but it, too, was ferociously involving, while the British horror-comedy Shaun of the Dead, the same year, combined deft wit with stomach-churning moments of unpleasantness.

In time-honored style, America has embraced its darkest fears with enthusiasm. The purely imaginary threat posed by the sudden inconvenient return of the dead has metamorphosed into a real threat in the minds of some people, who believe it can only be a matter of time. Max Brooks’s cleverly conceived The Zombie Survival Guide, published in 2004, spawned a new genre of survivalist literature. Zombie walks have become annual events attended by thousands of shambling, gore-spattered zombie lovers in cities across the United States and around the world, in Toronto, Paris, Sydney, Moscow and Warsaw. Purely for fun, of course, and often to raise money for a charity. “If a zombie is becoming too rowdy, use the bullhorn to keep them in check,” advise the socially minded organizers of World Zombie Day.

At the Zombie Apocalypse Store in Las Vegas, a journalist asks a couple whether they are worried about the zombie apocalypse. “We kinda hope it happens,” says the sweet young woman. Incredibly, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website has a page titled “Preparedness 101: Zombie Apocalypse.” The idea is that if you are ready and equipped to deal with zombies, more mundane emergencies such as hurricanes or an outbreak of flu should be a cinch. “If zombies did start roaming the streets, CDC would conduct an investigation much like any other disease outbreak.” That’s good to know, though if you have seen what happens to the CDC in The Walking Dead, you might be less reassured.

As a festive service to readers, I have assembled here a selection of promotional posters for the recent onslaught of zombie films along with a few early examples of the genre. But first, to give this some context, we should pose the obvious question. What is it about these horribly injured, putrefying ghouls with a craving for living flesh that makes them the most meaningful and improbably appealing of 21st-century monsters?

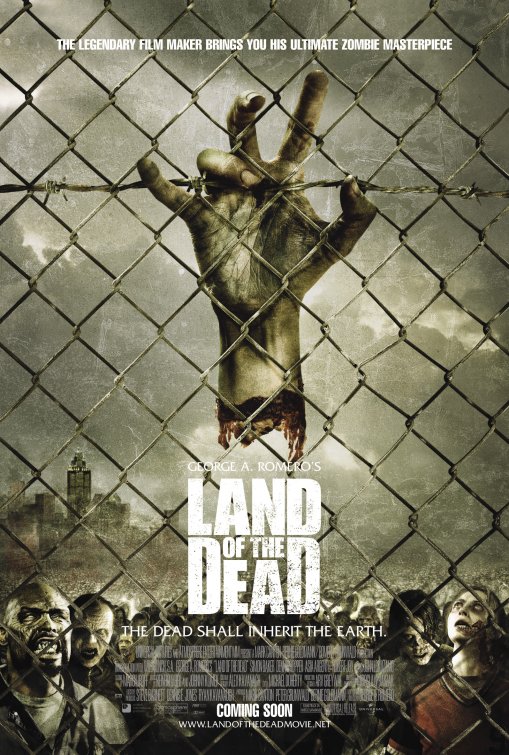

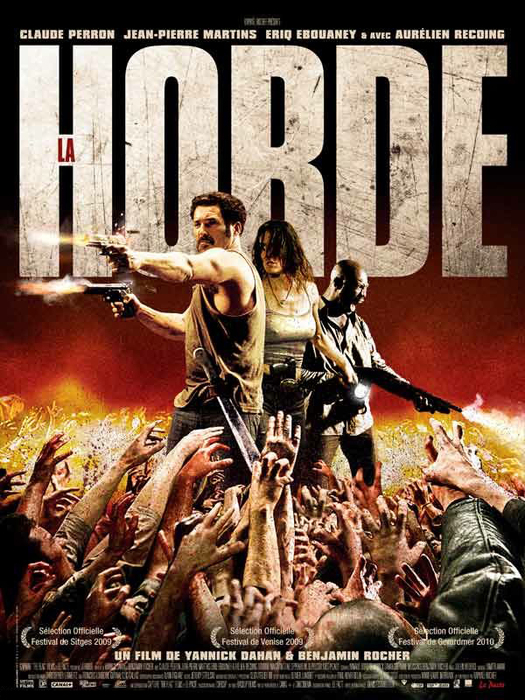

Zombies address deep contemporary fears and most of them focus on other people. From Romero’s Land of the Dead (2005) to the European zombie bloodbath La Horde (2009) — the infection is everywhere now — the zombie belongs to a burgeoning army of braindead invaders that threatens to outnumber, overwhelm and consume the living. The zombie symbolically expresses enduring concern about population growth, uncontrolled immigration and being overrun by outsiders that can’t be acceptably stated in plain terms in our liberal societies. “Ever felt like you were surrounded by zombies?” — Shaun of the Dead poster. At a time when we fearfully await the next devastating pandemic that we are constantly warned is overdue, the zombie is also a nightmare embodiment of our anxiety about contagion. One bite from this repulsive toxin-carrier and you are doomed to become one, even if you appear to survive the encounter.

Then there is our mounting fear of social breakdown (see the economy), a theme made startlingly real in The Walking Dead, which grafts the bleak, end-of-things atmosphere of the film version of The Road on to the standard zombie exploitation template to forge a vision of total collapse made even more disturbing by the plausibility of the characters: this really is what it would be like.

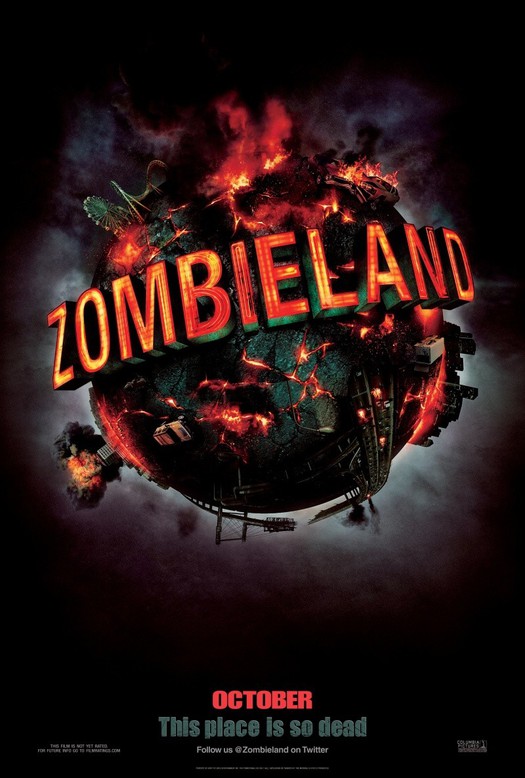

There’s an even less savory side to these fantasies. They are savagely violent, but for those struggling to survive the zombie apocalypse, this violence quickly becomes a matter of both urgency and routine, justified by the necessity — the absolute reasonableness — of exterminating creatures out to dismember and kill you and your few remaining companions. These films offer audiences the thrill of watching the living suffer harrowing attacks and losses followed by the satisfaction of seeing equally extreme violence inflicted on “once human” (but in point of fact still human) targets that we can abhor without social censure as we root for the living. The mechanism is particularly obvious in films such as Braindead, Shaun of the Dead and Zombieland, which try to disguise their purpose as pretexts for industrial quantities of bloodletting and disfigurement by cloaking acts of pathological violence and insanely spiraling body counts in slapstick comedy.

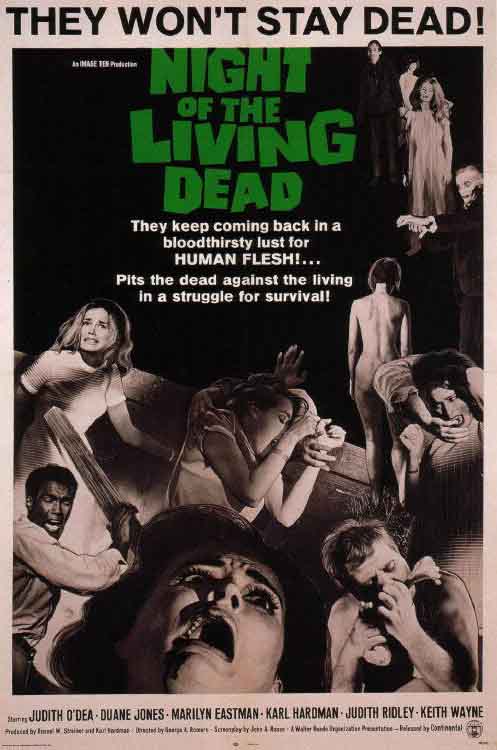

Night of the Living Dead, directed by George Romero, 1968

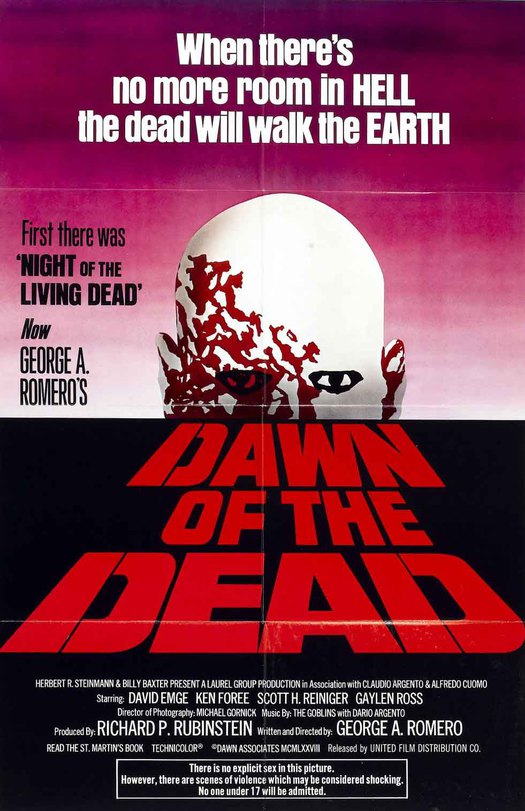

Dawn of the Dead, directed by George Romero, 1978

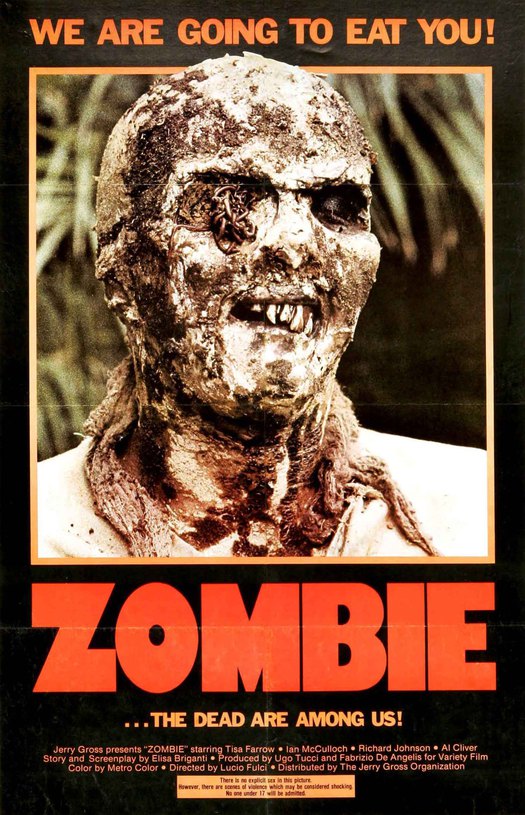

Zombie (also known as Zombie Flesh Eaters), directed by Lucio Fulci, 1979

The early posters aimed at a minority audience of horror fans had yet to arrive at a formula, though the Night of the Living Dead poster summarizes the mood of the film with some accuracy. A decade later, the Dawn of the Dead poster is too stylized to possess much bite. Its contemporary, Zombie, goes for the gross out, but it does have a slogan — “We are going to eat you!”— unmatched in the genre. Some of this uncertainty of approach can still be seen in the Dawn of the Dead remake poster, where the 1950s horror comic style of illustration bears no relation to the contemporary kinetic rush of a movie that opens with terrifying titles by Kyle Cooper, long a master of horror. The best part of the overly reserved, though blood-red, 28 Days Later poster is the timeline that charts the rapid descent from exposure to devastation.

28 Days Later, directed by Danny Boyle, 2002

Dawn of the Dead, directed by Zack Snyder, 2004

Shaun of the Dead, directed by Edgar Wright, 2004

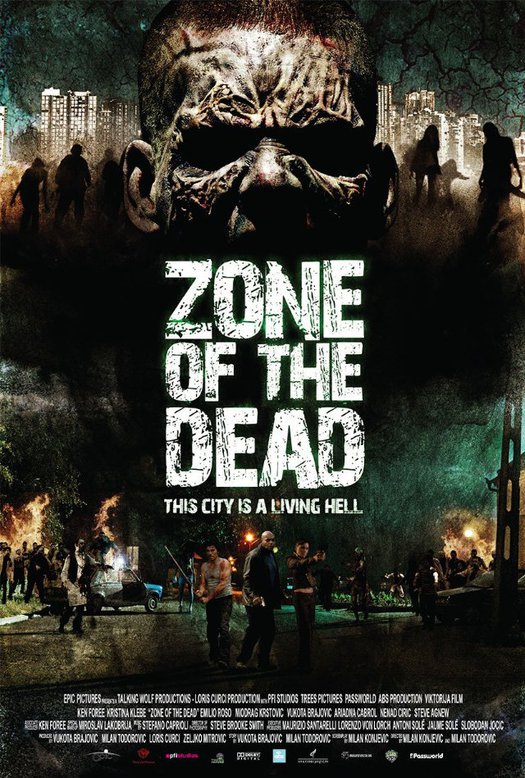

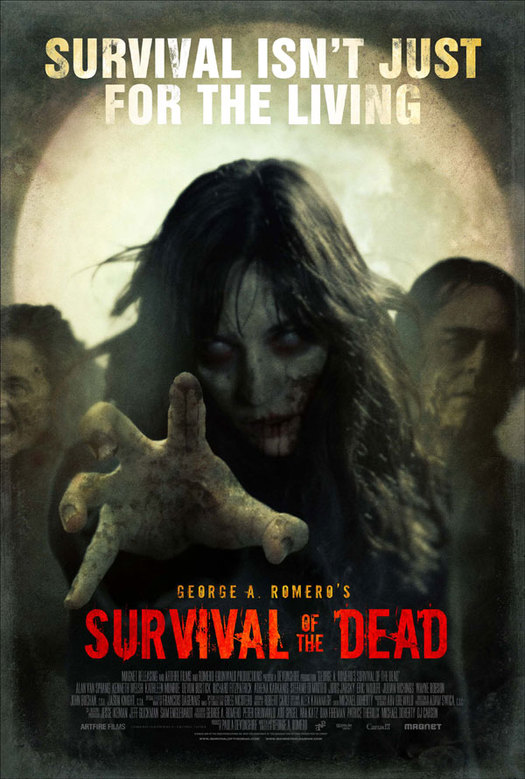

In the Shaun of the Dead poster, the genre alights on key elements of the style that now prevails. It’s a photographic image treated and intensified to make it look more cinematic. The almost cute zombies in the train have the greenish pallor of decay, the massive gravestones of type are scratched and battered, and there is a clutching hand. These devices have become routine in recent American zombie film posters and they can be seen in the poster for the Serbian zombie film Zone of the Dead (2009). For those who admire Romero at his best, it’s disappointing that the Survival of the Dead poster (2009) is in thrall to the same limited genre conventions, though it does feature a glamorous female zombie, which could be a marketing response to the participation by women in the zombie walks.

Land of the Dead, directed by George Romero, 2005

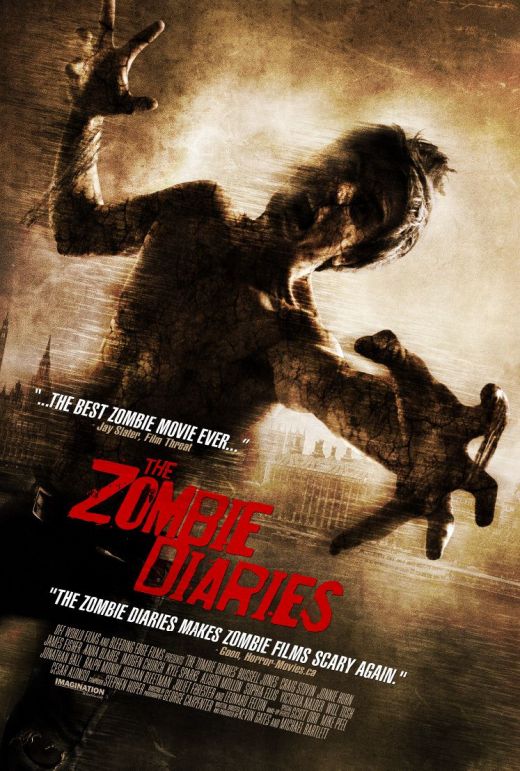

Zombie Diaries, directed by Kevin Gates and Michael Bartlett, 2006

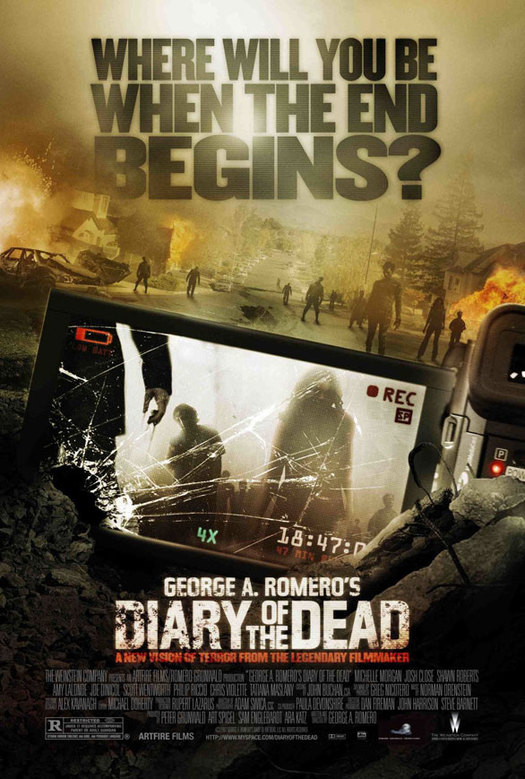

Diary of the Dead, directed by George Romero, 2007

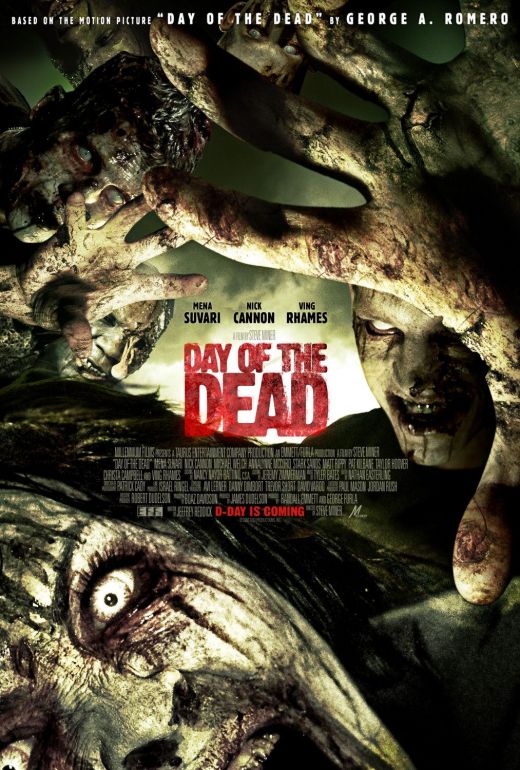

Day of the Dead, directed by Steve Miner, 2008

Zone of the Dead, directed by Milan Konjevic and Milan Todorovic, 2008

Survival of the Dead, directed by George Romero, 2009

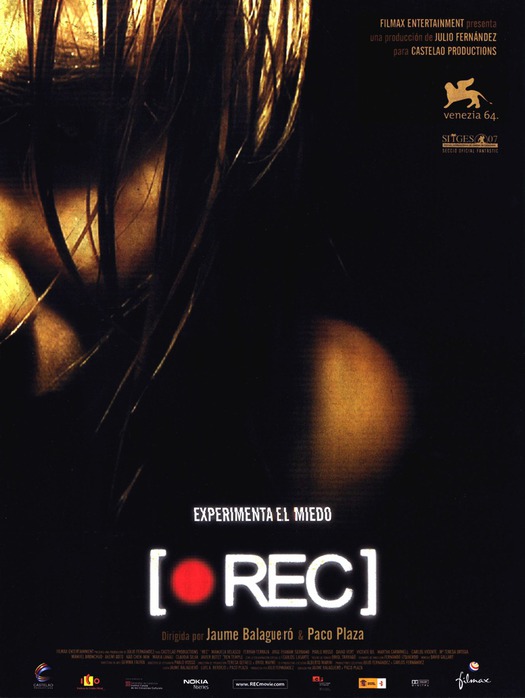

In this moldering company, the Zombieland poster achieves far more by picturing an entire planet trashed and burnt out by zombies than it could by showing the ravening mob. The poster for the Spanish film [Rec] (2007), one of the most imaginative and grueling zombie tales of recent years, makes no attempt to portray the visceral horror, presenting the film as a piece of European arthouse cinema, which in some ways it is (when it was remade in Hollywood as Quarantine, they stuck with the woman, but brought back the queasy green hue). La Horde, a French entry into the genre, has energy and violence levels that make some American efforts look sluggish. The poster self-consciously frames the story as a heroic last-stand action epic, with countless clutching hands emerging from a hellish inferno, but few visible signs of zombification.

Zombieland, directed by Ruben Fleischer, 2009

[Rec], directed by Jaume Balagueró and Paco Plaza, 2007

La Horde, directed by Yannick Dahan and Benjamin Rocher, 2009

We save the best until last. As the two Walking Dead posters show, when your audience is already hip to zombies, there’s no pressing need to show zombies in the picture. If the title hasn’t already done it for you, then the sickly green tinge should be enough to say: Undead Things Here. Add to this the incongruity and personal struggle of a lawman in a country with no law and the terrible aloneness of being a survivor in a post-apocalyptic world. But breathe easy: despite the virulence of the zombie plague, it’s only a story.

The Walking Dead, second series, 2011

See also:

Literary Horror from the Chapman Brothers

What Does H.P. Lovecraft Look Like?