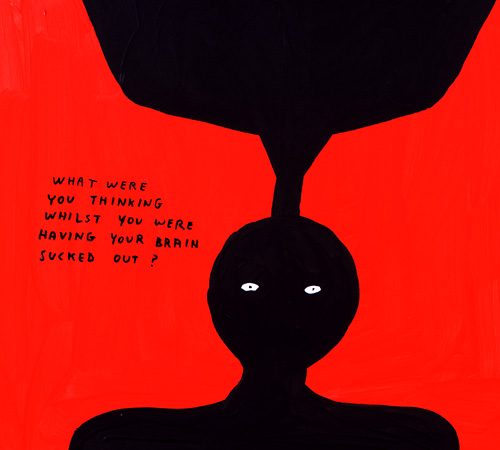

Painting by David Shrigley

When British book artist David Shrigley was 11, his father confiscated his Dungeons & Dragons set and threw it on a bonfire in the garden. Shrigley seems to have taken the game’s immolation in stride. “I remember looking out of the living room window, watching him burning this thing and seeing the little dice melting,” he recalls with a laugh. Shrigley’s father, a fervent Christian who belonged to an evangelical sect, knew a harmful influence when he saw one. “He had his reasons,” says Shrigley. “Maybe he saved me.”

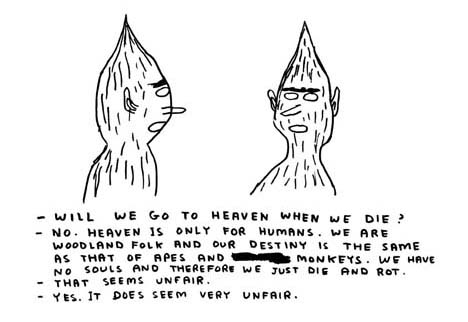

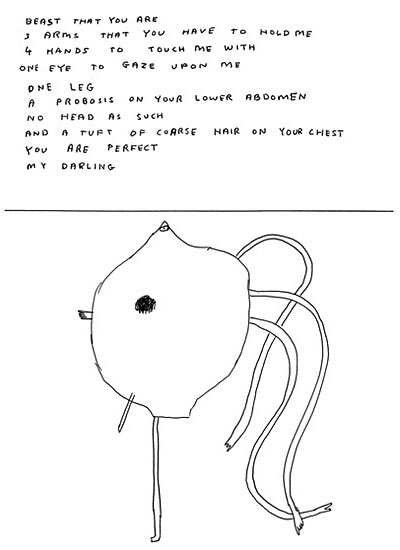

Anyone who has seen the collections What the Hell Are You Doing? and The Book of Shrigley, or any of Shrigley’s smaller books and postcard sets, won’t be surprised to learn that God and the Devil played a larger-than-average role in his childhood. One of Shrigley’s scratchy drawings, titled “What God Looks Like,” reveals the Deity to be a mild-looking overweight fellow. In another book, Shrigley explains in some detail what the Almighty wants from us. According to point 19, “God would rather we read a book than watched day time TV.” And He doesn’t, on any account, want us to give him clothes for his birthday. Money or a gift voucher would be fine.

From The Book of Shrigley, Redstone Press, 2005

Until Shrigley was 15 or so, he dutifully attended Bible study classes and Sunday school in Leicester, England, where he grew up, but then decided enough was enough and stopped going. He isn’t complaining, though, since those years left him with a peculiar way of thinking and enough material to last a lifetime. “I find the language of religion, particularly the language of Christianity, something amusing to subvert, I suppose. But then I think I’m a moral creature,” he says. “I believe in right and wrong.” In another drawing, “Time to Choose,” Shrigley confronts the viewer with three figures: Good (hidden behind a Ku Klux Klan mask), Evil (easily the most commanding and impressive, with his ram-like horns), and Don’t Know (the strangest of an odd bunch).

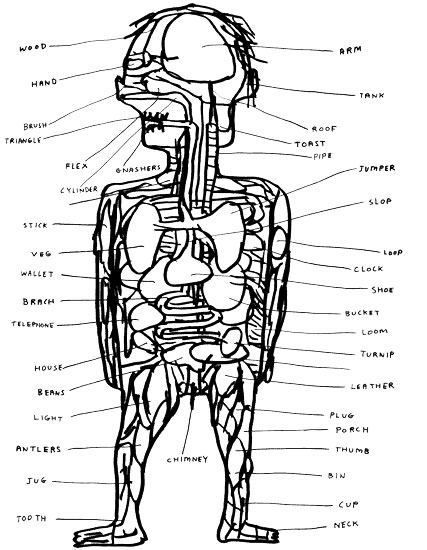

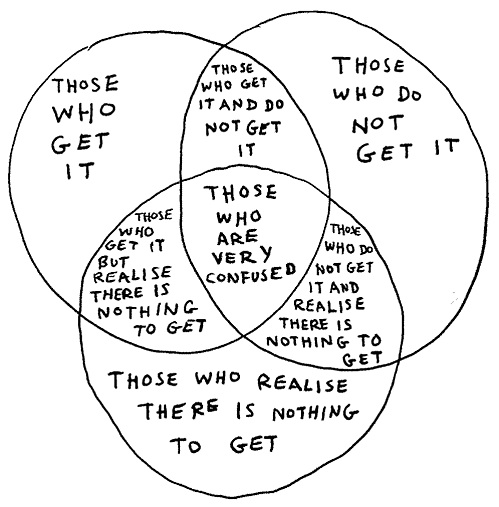

He is forever tempting and testing the viewer. British critic Michael Bracewell, the first to write about Shrigley in the mid-1990s, noted how his drawings “exist in the singular world of their own sealed vision.” While plenty of visual artists combine words and images, there is no other body of work quite like Shrigley’s in content or execution. He has created a Shrigleyesque universe, with its own verbal idioms, dysfunctionally shaky line, and dark psychological obsessions. He is both a gallery artist whose work appeals to art-world insiders and a maker of popular books — 39 to date — that connect with a broad, non-art audience. His work features in Vitamin D, Phaidon’s international survey of artists’ drawing, but also in Pictures and Words, a round-up of narrative illustration, alongside Joe Sacco, Jordan Crane and Marjane Satrapi.

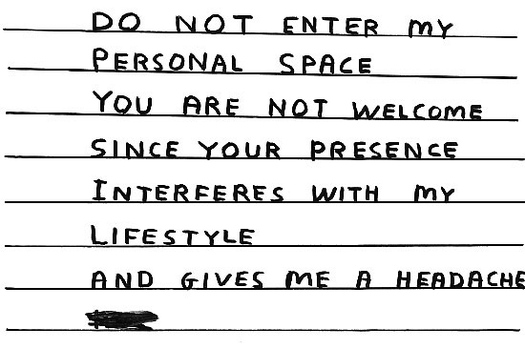

From The Book of Shrigley, Redstone Press, 2005

Shrigley started young. “I’ve always been into speech bubbles,” he says. “I’ve always drawn. From when I was a little kid, I’ve been into expressing myself in that way, using words and pictures.” He went to Glasgow School of Art to study fine art but never imagined himself as an artist. Graduating in 1991, when the Young British Artists had yet to make an impact, Shrigley decided to become a cartoonist, even though he had no interest in cartoons or comic books. Merry Eczema, a limited edition published in 1992, showcases a tighter, more conventional-looking Shrigley. He used Letratone to give his characters graphic presence and put a tidy box around each drawing. Even so, there are hints of what would follow. The last cartoon shows a cluster of dirty scribbles with the statement, “Once soiled one can never fully return to cleanliness.”

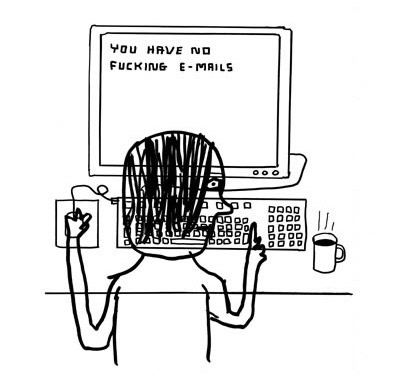

“That is the real mannered stuff,” says Shrigley. “It’s just an odd phase I went through that lasted a year or so and then stopped and returned to normal.” He stayed in Glasgow (where he still lives) and for the next few years he did odd jobs and filled his notebooks with pictures and writing. His breakthrough came in 1996 when Bracewell, his champion, commissioned Err for Book Works, the London publisher of low-cost artists’ books; it’s now in its eighth printing. The book appeared in a “new writing” series, a reminder that Shrigley’s texts are fundamental to his work. Some of his “pictures” consist only of writing delivered in uneven lines of clumsily formed capitals, and almost any piece depends on words for its atmosphere and effect. Yet Shrigley still resists the suggestion that he is any kind of writer. His compositional method is a form of graphic automatism. He presents his intuitive scrawls unrevised, exactly as they come to him.

David Shrigley

“That’s why there are lots of spelling mistakes and crossings out,” he says. “I’m not pretending to be bad at spelling — I am bad at spelling. I also genuinely make a lot of mistakes when I write things down.” Any editing amounts to throwing the unusable ones — most of them — in the garbage.

In 1998, the London independent publisher Redstone Press, known for its quirky diaries and boxed sets, published Shrigley’s Why We Got the Sack from the Museum. Fourteen more Shrigley publications have followed. “It wasn’t deliberate. It just happened,” says Redstone founder Julian Rothenstein. “I just loved his work when I saw it. We get on very well. I’ve been good for him and he’s been great for me.” Shrigley receives a degree of attention he could never expect from one of the big art-book publishers, who would be unlikely to release so much material. “We have an unbreakable bond now,” Shrigley says. “I guess until one of us dies we will always have that collaboration. Julian’s my friend, and he lets me do whatever I want. There’s not any reason to change.”

David Shrigley

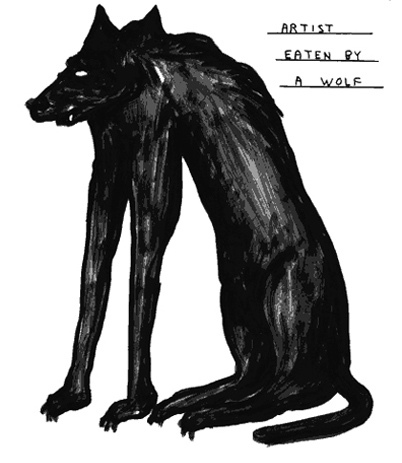

Shrigley’s books aren’t “artists’ books” in the established sense of expensive limited editions aimed at the art market. “The roughness and lack of fine-book decorum of the books and their titles elegantly express the self-publishing independence of their production,” says art critic Mel Gooding, a regular Redstone collaborator, and editor, with Rothenstein, of The Book of Shrigley. Nor is the humor section of the bookshop quite the right place for Shrigley’s creations. “I think his work is hilarious, and smart, and immediate,” says Steve Mockus, an editor at Chronicle, which publishes his books in the U.S. “And dark, but dark is good.” For all the laughs, though, the Shrigley take on things — summarized in one drawing as “Pointlessness boredom desperation utter confusion” — is bleak in the extreme. Shrigleyworld is often a place of violence and madness where the strong prey without mercy on the weak. In the hospitals, doctors eat the flesh of corpses and nurses drink patients’ blood. “Who shall we kill next?” a blob person asks. “Some animals,” its companion replies. In the harsh world of shapes, we learn in another drawing, the weak cube must die. A picture shows smoke belching from a chimney: “Q. What are they burning in the furnace today? A. Proof of your existence.”

David Shrigley, from Worried Noodles — The Empty Sleeve, Tomlab, 2005

Shrigley’s people are edge-dwellers. They have lost their bearings and their states of mind are fractured and extreme. One figure announces that he lives beyond the margins: “I am not allowed to join society because I am unable to grasp the nuances of human interaction.” Shrigley draws a “nutcase,” his eye sockets vacant, his mouth a brutal slit: “What he is imagining we can only imagine.” The image has a bottomless horror, but it’s also very funny. If we can imagine what this deranged fantasist might be thinking about, then we must be nutcases too. In the same book, Grip (2000), the text below some angry scribble informs us that even the smoothest of objects are rough and bumpy when seen under a microscope: “When I think of it I am filled with despair.”

But the “despair” is about something more than strange compulsions and peculiar ways of seeing things. Shrigley occasionally throws out an image with such directness and urgency that it wouldn’t take much to turn it into a protest poster. In one drawing in The Book of Shrigley, a hand holds out a cup labelled “The Poor.” Defying gravity, water gushing from a faucet bends away from the receptacle. Yes, we might ask, how does that happen? Elsewhere, a giant pair of boots representing “the owner of the means of production” stands in a position of absolute mastery, quite literally on top of the world.

From The Book of Shrigley, Redstone Press, 2005

Shrigley is an affable, easy-going person to spend time with, and this gives added force to the emotion in his reply when asked a direct question about his view of humanity. “We exist in times when wars are fought for financial reasons rather than to protect human life,” he says. “Human beings, it seems, are just horrible, greedy, terrible creatures. All they’re interested in is the accumulation of wealth, and they have an obsession with tittle-tattle and the most tedious, tawdry aspects of each other’s lives.” Shrigley is not a political propagandist, and he prefers, as a rule, to express these views in less direct ways. Nevertheless, these are the terms in which we should understand his endlessly repeated scenes of violence, anomie, social breakdown, and unthinking callousness toward others. In Let’s Wrestle (2004), his style of drawing is cruder and scratchier than ever, and the malformed, naked figures that fill the pages express a new intensity of malevolence.

In recent years, Shrigley has done illustrations for magazines and newspapers; he had a regular spot in the Guardian’s Saturday magazine. His concepts have been turned into products such as pillowcases. He made a pop video for the British band Blur, collaborated with director Chris Shepherd on a short film, Who I Am and What I Want, based on one of his books, and went on to make other short animations. His drawings are more ordinary in motion and lose much of the pent-up weirdness they have on the page.

David Shrigley, from Leotard, BQ Gallery, 2003

The unpretentious paperback book is the natural medium for Shrigley’s art. His pieces gain from being seen by the dozen, one after another. They have the casual intimacy of doodles and they don’t need gallery dimensions to communicate their point. Shrigley sits alongside other artists working within pop culture, from Robert Crumb to Chris Ware, who have used words and drawings to express their vision, but he seems concerned to keep his distance. “I’ve no interest in any of these people, to be honest,” he says. “I like what they do, but I don’t see any affinity with it in terms of my own work. In terms of influence, I suppose I’m much more interested in literature.” To underline this, The Book of Shrigley features extracts from texts by two writers Shrigley admires, Franz Kafka and Donald Barthelme.

Shrigley’s insistence that he is, at root, a fine artist, with a home in the gallery, might allow him to keep his options open, but it feels unexpectedly old-fashioned in its assertion of traditional pop-culture/art-world distinctions. It also raises all the old questions about what makes something art. Some artists seem to believe that anything can be art just so long as people who are designated “artists” by the art establishment do the choosing. But if anything really can be art, then art might come from anywhere, including the comic book. The key factor is the depth of content. By using the basic tools of the comic strip, however much he might bend and abuse them, Shrigley has a lot more in common with people like Crumb, Ware, Gary Panter, and Daniel Clowes than he cares to admit. His books remain the most compelling part of his output. It would be perverse if he were ever to abandon a medium he has gripped by the vitals and reinvented for his own purposes.

From The Book of Shrigley, Redstone Press, 2005

This article was originally published under the title “Evil Genius” in Print magazine, May/June 2006. This slightly updated version is its first appearance online.