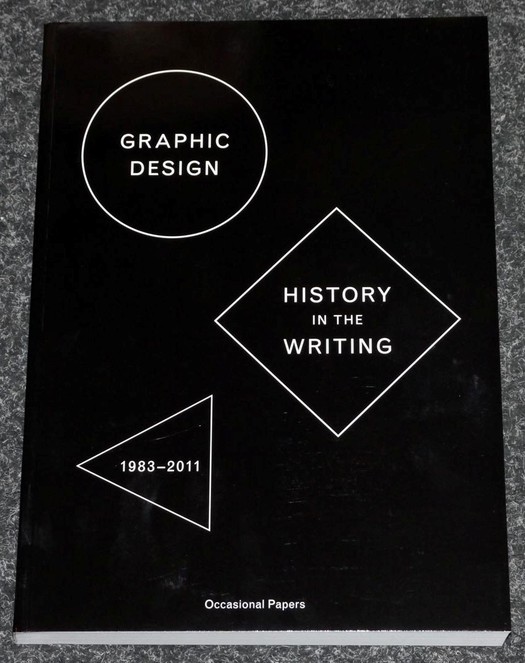

Graphic Design: History in the Writing published by Occasional Papers. Designed by Sara De Bondt.

Photo: Motto Distribution

Graphic Design: History in the Writing received a brief mention in OBlog, but I’d like to return to the book because this collection is an extremely useful volume that anyone with an interest in graphic design history should see. It’s also a very heartening initiative. The book’s publication by Occasional Papers — a small imprint started by Belgian designer Sara De Bondt and art historian Antony Hudek — is a sign that the project of graphic design history is passing to a new generation, as it must if it’s going to develop. The volume, edited by De Bondt and Catherine de Smet, a French writer and academic, is an offshoot from their jointly organized “Graphic Design: History in the Making” conference at St Bride Library, London in May 2011.

I should declare an interest here since I took part in that conference and I have two texts from Design Observer in the book, a dialogue with Denise Gonzales Crisp and an essay about the relationship of graphic design history and visual studies. Many of these writings are much less easy to locate, which is why collections like this are so valuable for casual readers and researchers alike. The book opens with Massimo Vignelli’s much-cited, agenda-setting keynote from a 1983 symposium about graphic design history at Rochester Institute of Technology: “We’ve got to insert some level of culture, some level of history, some level of philosophy,” he insists. “We need to provide a cultural structure to our profession.” The editors choose to date the emergence of graphic design history as a mission and a putative discipline from this point.

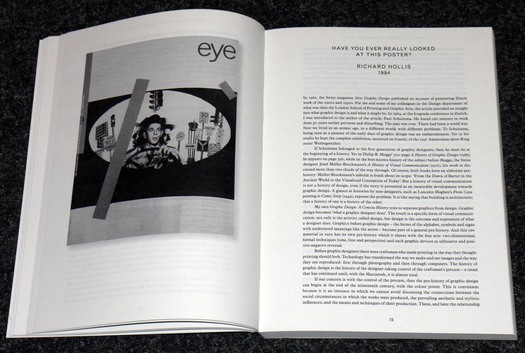

“Have you ever really looked at this poster?” by Richard Hollis, first published in Eye no. 13, 1994.

Photo: Motto Distribution

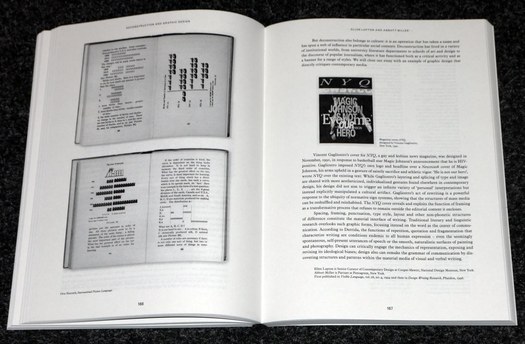

“Deconstruction and Graphic Design” by Ellen Lupton and Abbott Miller, first published in Visible Language, 1994.

Photo: Motto Distribution

There are key texts by Philip B. Meggs, Robin Kinross, Jeremy Aynsley, Ellen Mazur Thomson, and Martha Scotford, whose “Is there a Canon of Graphic Design History?” (1991) remains a foundational study. Andrew Blauvelt’s three issues of Visible Language devoted to new perspectives on graphic design history in 1994 are rightly reprised with six crucial essays, including pieces by Scotford (again), Victor Margolin, and Steve Baker, a sophisticated thinker who bailed out of graphic design studies too soon. There are later texts by Johanna Drucker, Brian Donnelly (“Locating Graphic Design History in Canada”), Teal Triggs, Catherine de Smet, and Steven Heller, who has made a huge contribution to the development of graphic design history, not least by creating and nurturing so many platforms for discussing the subject — both in print (the collection draws on his book Graphic Design History) and in the ground-breaking series of “Modernism and Eclecticism” conferences in the late 1980s and 1990s.

If this line-up sounds too predictably Anglo-American, the editors readily acknowledge the limits of their overview, but make the reasonable argument that it was important to start with the field as they found it in English-language writing. It’s good to see an English translation of De Smet’s “Pussy Galore and the Buddha of the Future” and English-speakers would clearly benefit from the availability of many more translations of significant writing in other languages — theoretical discussions and explorations of local history — though this is often a prohibitively expensive undertaking. A follow-up volume, perhaps? The survey suggests the need for “further cartography” and we can only hope that it helps to inspire an inquisitive new generation of map-makers to enter this still only patchily charted terrain.

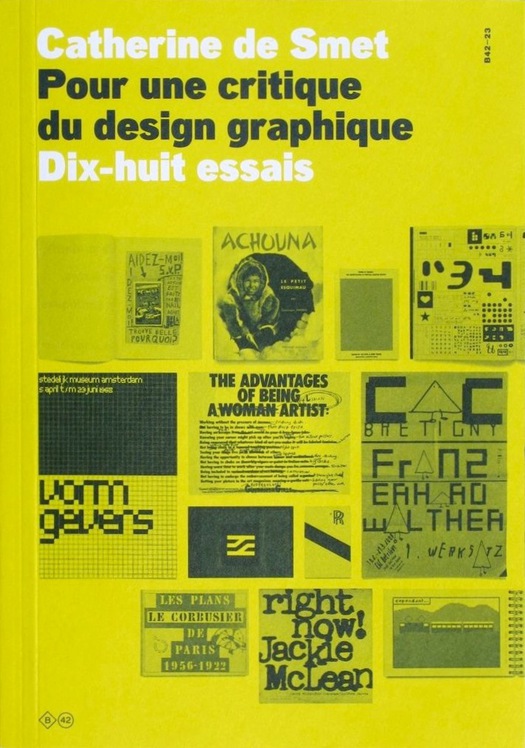

Pour une critique du design graphique published by Éditions B42, 2012. Designed by deValence

Graphic design history enthusiasts fluent in French should also be sure to dip into De Smet’s new anthology, Pour une critique du design graphique. Dix-huit essais (For a criticism of graphic design: Eighteen essays). This attractively designed volume is published by Éditions B42, a designer-led outfit based in Paris that’s very similar to Occasional Papers in its graphic interests, typographic felicity and critical spirit. De Smet’s topics include jazz album covers, Wim Crouwel, the Swiss designers Norm, the “Children of the World” series of books published in France in the 1950s and 1960s, and the relationship between architects and graphic designers. For a book with this highly readable page size, Pour une critique is copiously illustrated; everything is in color, too. The collection deserves translation and I hope B42 can make this happen soon.

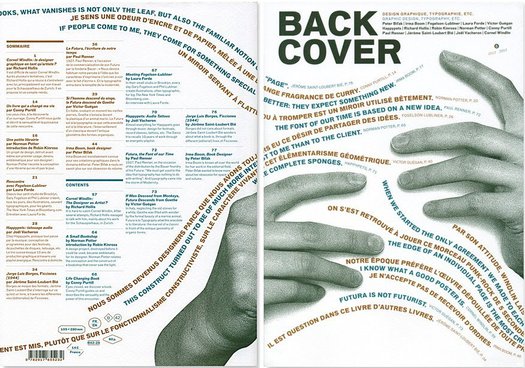

Front and back cover of Back Cover no. 5, 2012. Designed by deValence