The Museum of Innocence at the corner of Çukurcuma Street and Dalgiç Street, Istanbul

A while back, I wrote here about The Museum of Innocence created in Istanbul by the Turkish novelist and Nobel Prize winner Orhan Pamuk. This small, beautifully realized, vertical display, which occupies a burgundy-hued house in the city’s Çukurcuma neighborhood, is a parallel project planned for many years by Pamuk as a development of his 2008 novel, also titled The Museum of Innocence. In my earlier post, I wanted to show pictures of the museum’s displays, but hadn’t been able to take any because photography isn’t allowed. I bought the Turkish edition of The Innocence of Objects, a richly illustrated book about the museum, and have been waiting for Abrams’ English translation. It’s just come out and Pamuk’s text about the project is as illuminating as it promised to be. All the pictures by Refik Anadol shown here are taken with permission from the book.

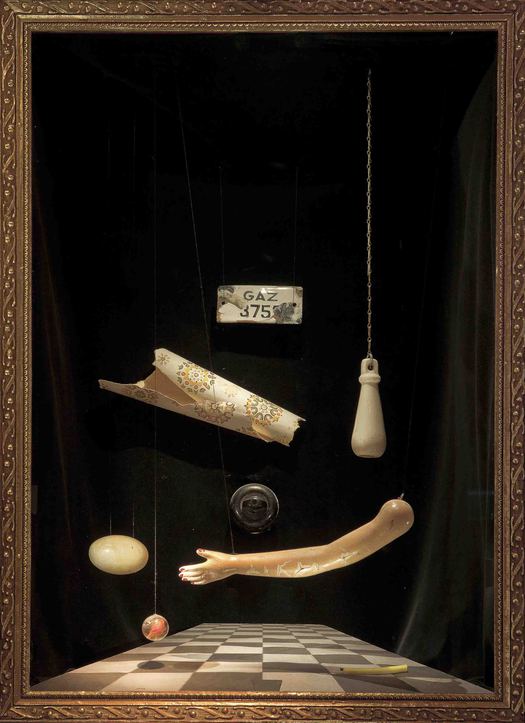

Orhan Pamuk’s numbered boxes correspond to chapters in his novel The Museum of Innocence

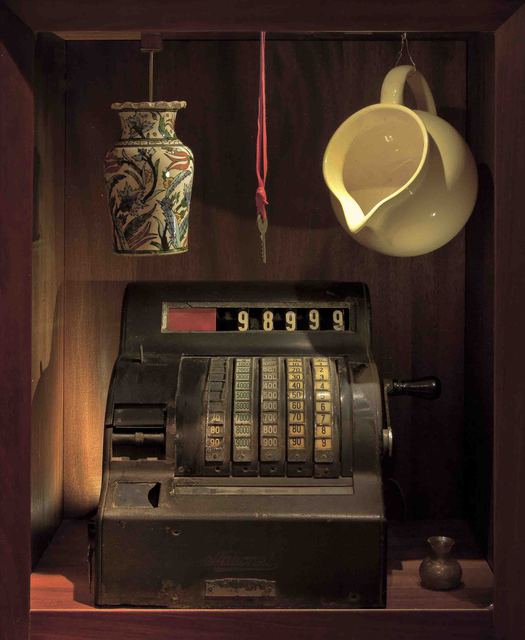

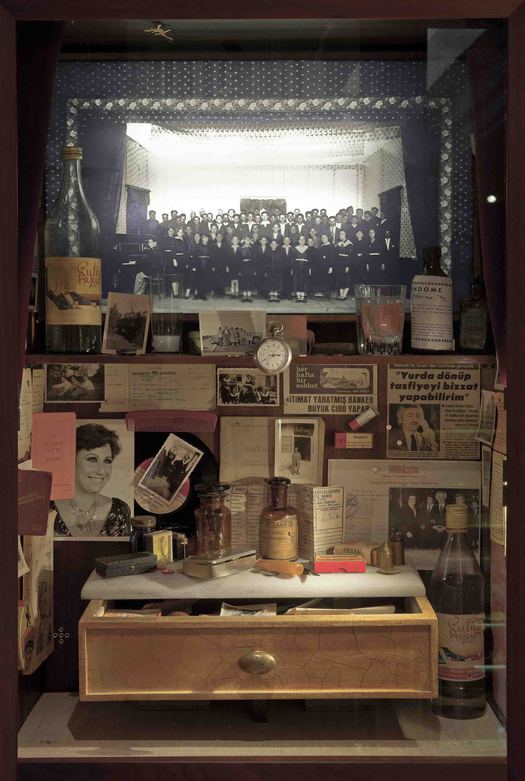

In his museum, Pamuk set out to create a glass-covered box, or other visual interpretation, to represent each of the book’s 83 chapters, giving each box the corresponding title. This huge task isn’t quite complete (will it ever be?) and red curtains conceal several unfinished boxes. Pamuk spent years scouring flea markets and junk shops for the objects in the displays, which encapsulate and encipher moments in the story and in his characters’ lives. In a section of the book titled “Waiting for Objects,” he describes how in Istanbul from the 1960s to the 1980s a new generation of collectors emerged whose houses soon became dusty repositories full of piles of old papers and heaps of curios, often at the cost of alienating the collectors’ families, who were horrified by this uncontrollable compulsion to hoard. “These ‘sick’ collectors were fully aware that their attachment to objects stemmed from personal heartbreak and sorrowful life histories,” writes Pamuk, “but they remained honestly convinced of the importance of their contribution to the very society that mocked them.” One day, the hoarders believed, their pieces could become the basis of museums and libraries. Pamuk recalls visiting these eerie private archives as a child: “we always felt, with a shiver, that the objects were communicating with each other.”

Box 6, “Füsun’s Tears”

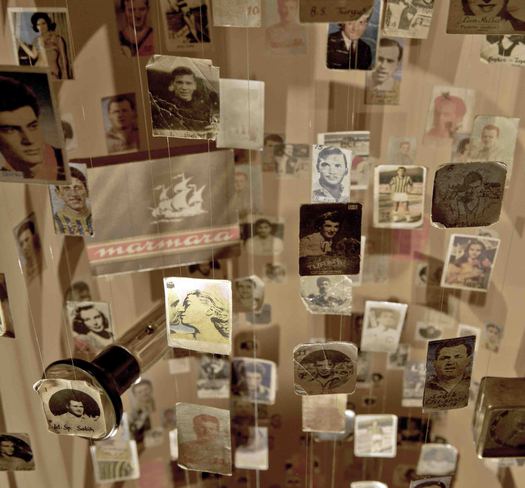

Box 12 (detail), “Kissing on the Lips”

This perception that insentient objects, adrift from their original settings and emotional contexts and coopted into complex new configurations, are somehow exchanging vibrations of meaning pervades the Museum of Innocence. Pamuk writes:

What I found most enthralling was the way in which objects removed from the kitchens, bedrooms, and dinner tables where they had once been utilized would come together to form a new texture, an unintentionally striking web of relationships. . . . Their ending up in this place after being uprooted from the places they used to belong to and separated from the people whose lives they were once part of — their loneliness, in a word — aroused in me the shamanic belief that objects too have spirits.

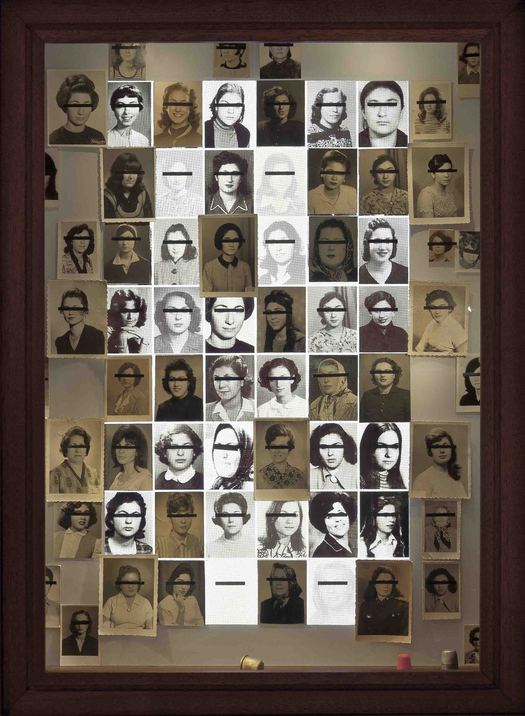

Box 15, “A Few Unpalatable Anthropological Truths”

Women “violated” and dishonored by men reluctant to marry them were shown in the Turkish press with black bands over their eyes. Adulteresses, rape victims and prostitutes received the same treatment.

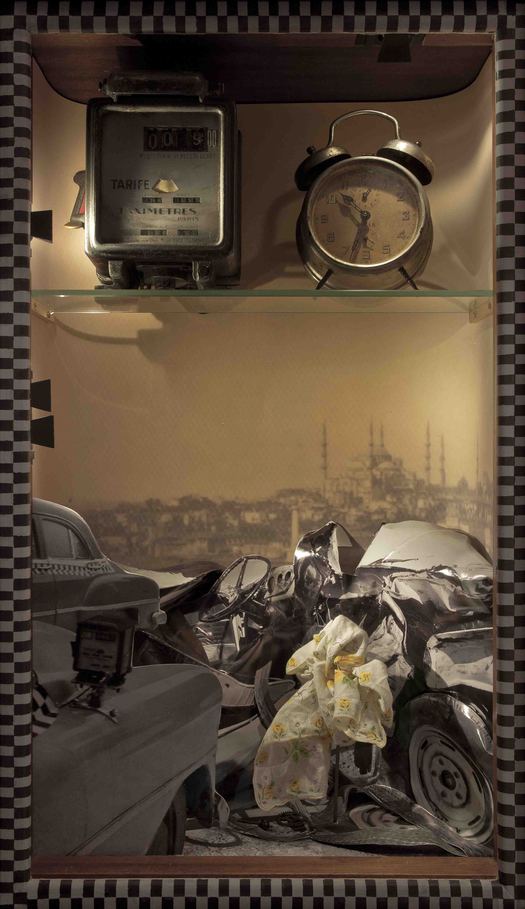

Box 17, “My Whole Life Depends on You Now”

The catalogue section of The Innocence of Objects presents the boxes in sequence just as visitors encounter them in the museum. The displays often include old photographs that Pamuk found in flea markets and the book shows many of these pictures as freestanding images for closer examination. There are identity cards, apartment name signs, photographs of ships on the Bosphorus, postcards of the Istanbul Hilton, collectable cards devoted to footballers and film stars, people posing merrily in groups at social occasions, and families standing proudly together in front of their cars — at a time when car ownership was still a privilege and talking point. Throughout the book, Pamuks adds bittersweet reflections and recollections of his early life in Istanbul.

Box 37, “The Empty House”

Box 74, “Tarik Bey”

Photographs: Refik Anadol

See also:

The Strange Afterlife of Common Objects