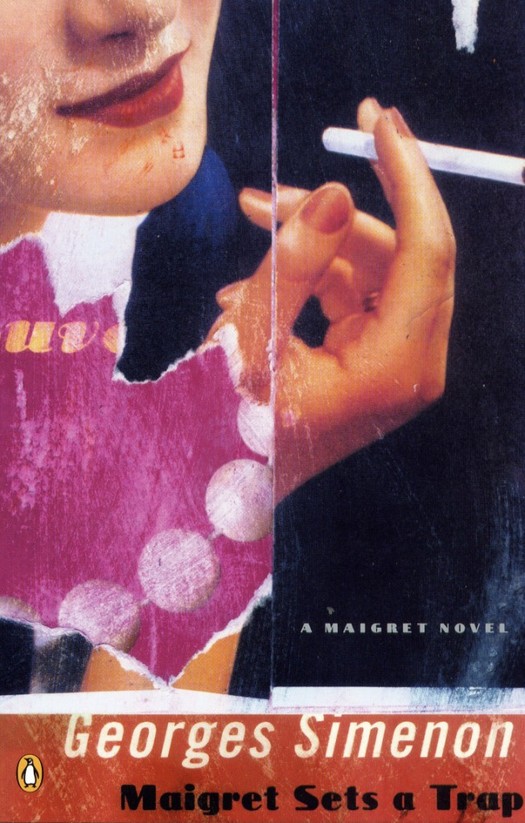

Book cover by Jamie Keenan, Penguin, 2004

Consider this image of a woman holding a cigarette. Isn't it — I'm afraid there's no way around this — rather beautiful? Even if you hate smoking, does it leave you completely unmoved?

I had better say at once that I am not now, never have been and have no plans to become a smoker. I tried it when I was 13, puffed my way through half a packet and knew it wasn't for me. This wasn't intolerance. Back then, smoking was normal and, in daily life, largely unquestioned. Smokers might struggle to give up, as my father did later, but it wasn't a continuous public health issue in the way it is now. It didn't generate the moral anger, self-righteousness and sense of disgust. Trying the cigarettes, which I did mainly to impress a girl, only confirmed the disinclination I felt in the first place. I had already done a decade or more of passive smoking (we didn't call it that in those days) in the back seat of the family car.

Still, a part of me has always liked the idea of smoking. Leaving aside how nasty it smells and what it's doing to a person's lungs, heart, brain and potency, it does look good. That slender white tube of death in someone's fingers presents a wonderful image. It endows smokers with poise. It gives them a way of filling the moment and something to do with their hands. Their bodies fall into expressive poses. They look convivial, relaxed, part of the picture. Smoking is a way of connecting with other people, or at least with other smokers, and smokers used to seem cooler, edgier, more interesting. They were risk-takers and rebels. Willingness to inhale acrid emissions into the body's vulnerable cavities and transform this life-threatening addiction into a source of deep satisfaction and pleasure set smokers apart from non-smokers, who lacked the uncompromising drive for experience and indifference to mere good health that bound a smoker to his cigarette.

Who would be a smoker today? It must be sickening in more ways than one. In the US and Britain, the smoker has become a pariah. "Smoking is now shorthand for being a loser," writes a British columnist. As I was leaving a publisher's premises the other day, I saw the managing director heading out into the street for a furtive smoke. His staff had delivered an ultimatum, he confided. He couldn't even light up in the confines of his own office.

Has any leisure activity engaged in by adults (and, unfortunately, children) ever been so thoroughly stigmatised by a relentless barrage of social censure, medical disapproval and bad publicity? In a culture otherwise swamped with unregulated branding, the graphic counter-attack on the cigarette packet, on its visual integrity as a design and its brand equity, normally regarded as commercially sacrosanct, is a remarkable sight to behold. In Europe, in the US and around the world, outsized health warnings in ugly typography now disfigure and subvert the best efforts of the brands' designers to embody the fast-fading allure of the cigarette.

Canada has already gone to the next stage and plastered photographs of ruined teeth and cancerous lungs over the packets. In October 2004, the European Union introduced 42 specimen designs, combining imagery with a warning slogan, which member countries are encouraged to use. They are even more unpleasant than the Canadian images — not least the man with a bulbous red tumour flourishing under his chin. As the tide rushes out for smoking, the widespread use of extreme visual shock tactics on the packs is approaching just as fast. "I make no apology for some of the pictures we are using," said David Byrne, the European Commissioner for Health and Consumer Protection. "The true face of smoking is disease, death and horror — not the glamour and sophistication the pushers in the tobacco industry try to portray."

Will such brutal wake-up measures work? It's far from certain. All the finger-wagging and the endless dire warnings can make hardened smokers angry at being lectured even less inclined to kick the habit. They also end up attracting new tobacco converts, including young people. Smokers' rights groups are fighting back. You can buy ironic stickers to obliterate the health warnings — "Long painful deaths are in these days" — or you can simply remove the cigarettes, throw the pack away and store the objects of your shameful craving in a stylish case. That's what I would do in their position. Some smokers still mourn the passing of Death cigarettes, a 1990s brand that told it like it was, adding perversely to the glamour. British artist Damien Hirst, who creates work from discarded cigarette butts, confirms that, for some smokers, the habit's deadliness is a crucial part of its existential appeal. "Smoking is the perfect way to commit suicide without actually dying," he says. "I smoke because it's bad, it's really simple. So people can't come up to me and say, oh it's bad for you, don't do it ... I don't trust people who don't smoke." He even designed a pack for Camel.

The most artful defence of smoking can be found in American literary critic Richard Klein's book Cigarettes are Sublime, which he wrote, he explains, as a way of trying to give them up. For Klein, the cigarette is a "crucial integer of our modernity" and he regrets that "their cultural significance is about to be forgotten in the face of the ferocious, often fanatic and superstitious, and frequently suspect attacks upon them ..." He has a point. When you look at photographic portraits made half a century ago of film stars such as Bogart and Monroe, or writer/philosophers such as Sartre and Camus, the smouldering cigarette is more than just a ubiquitous prop, it's a revelation of character, a measure of seriousness, almost a marker of being. Smoking tends to look best pictured in black and white because the slim cylinder's whiteness becomes luminous, the smoke ethereal. In Karsh's picture of Bogart, the punctum — to use Roland Barthes' word — is the smoke trail like soft gauze ascending from the long burning tip of Bogart's cigarette. Is "sublime", in the sense of terrible beauty, not exactly the right word to describe the dark pleasure such images evoke?

Of course, you could argue that photos like this were just another kind of advertising, doing the cigarette companies' dirty work for them, seducing the viewer into believing the most destructive kind of lie: smokers are intelligent, sexy, popular, manly, or tough. These pictures, taken before tobacco's devastating effect on health was understood by the public, are almost unthinkable now. Film stars caught smoking in movies today find themselves accused of encouraging impressionable teenagers to take up the offensive habit, and even writers might have qualms about being so irresponsible as to flaunt their addiction in a publicity shot.

An era is slowly ending. Much as I savour the image of the smoker, if not the noxious fumes, this is a good thing. What's more, the level of righteous graphic intervention by government creates a fantastic international precedent. Compared to some other notable ills, smoking has arguably received an unfair share of the heat. Next up, we could look at guns and the American consumer; the arms trade; the huge annual death toll on the world's roads caused by cars; advertising aimed at brainwashing young children; and, oh, maybe even the effect of massive levels of over-consumption on the global environment.

Put a warning label on that.