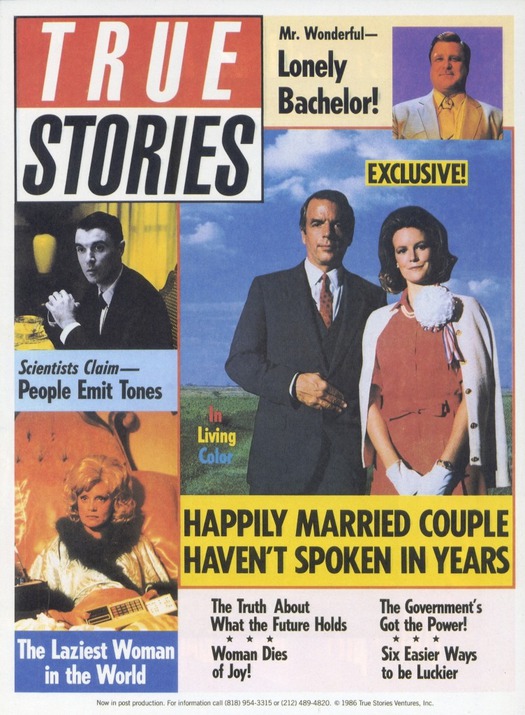

Unused poster for David Byrne’s True Stories, 1986. Designed by M&Co

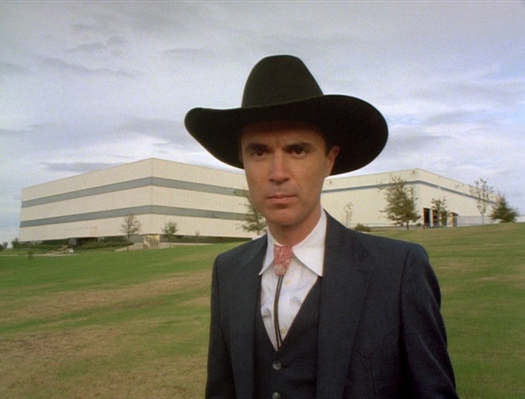

In a teasing interlude about architecture in the film True Stories (1986), directed by David Byrne, the narrator, played by Byrne himself, enthuses about metal buildings. Architects don’t realize it, he suggests, but these structures represent the fulfilment of modern architecture’s dream. There is no need to engage an architect to build one. “You just order ’em out of a catalogue, just pick out your color, the size you want, number of square feet, which style, what you need it for . . . You’re all set to go into business. Just slap a sign in front.” Here, the “decorated shed” identified by Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour in Learning from Las Vegas reaches a point of expedient reduction and commercial utility beyond which “architecture” can progress no further.

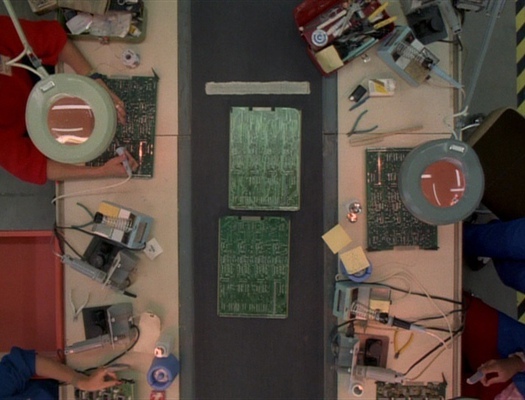

True Stories arrived in cinemas around the same time as other American films quickly identified by critics as postmodern, notably David Lynch’s Blue Velvet and Jonathan Demme’s Something Wild. Byrne’s three-year project, his only full-length feature to date, was unique, though, in making the postmodern culture of the mid-1980s, including the visual environment, its subject. True Stories doesn’t contain any examples of overtly postmodern design, except for an extraordinary fashion show, with surreal costumes by Adelle Lutz (later Byrne’s wife) resembling bricks, a classical column, a wedding cake, leaves and grass, but the film is itself a highly designed postmodern artefact — Byrne studied design at the Rhode Island School of Design — that now looks completely of its era. Baffling as it might have seemed to 1980s viewers expecting a conventional narrative about provincial life in Texas, True Stories’ report on the fictitious town of Virgil was also highly prescient. Its themes of surburban sprawl, recreational shopping and mall culture, the pervasive influence of advertising and media, the fast-developing computer industry (represented by Virgil’s main employer, Varicorp) and the emergence of new social priorities and values would come to preoccupy, and vex, many social commentators and cultural critics.

Byrne, the narrator, visits the Varicorp building outside Virgil, Texas: “It’s a multi-purpose shape — a box.”

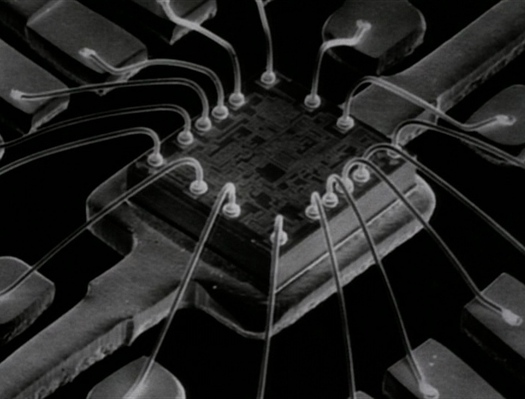

The computer production line at Varicorp

The film’s attitude to these issues is playfully ambiguous. Who is this blandly inquisitive narrator in a cowboy shirt and Stetson and why has he come to Virgil? Although the characters are happy to talk to him about their lives, he isn’t situated within the film’s world as a professional investigator — journalist, ethnographer or documentary film-maker — with reasons to be telling its story. Yet he repeatedly addresses the audience through a camera that other people in the film mostly appear not to notice. The first time we see Byrne he is delivering a lecture in a theatre, using a screen, through which he then steps. Driving his convertible in front of an obviously projected backdrop, he manipulates the steering wheel with exaggerated, unrealistic movements. Self-reflexive devices such as these characterize the postmodern film. Later, a girl asks whether the other characters can hear the music that has started on the soundtrack, presaging further breaks in the film’s illusion of reality. Intertitles announce each section of the narrative. In True Stories, Byrne would seem to be playing “David Byrne,” making the entire film a kind of three-dimensional, illustrated lecture. Cruising the freeways: “They’re the cathedrals of our time, someone said. Not me.”

Cruising the freeways: “They’re the cathedrals of our time, someone said. Not me.”

True Stories is in any case a hybrid, another characteristic of postmodern cinema. Byrne’s source material for many of the people and incidents comes from stories he found in Weekly World News and other trashy American tabloids. The musical sequences based on songs written and performed by his band, Talking Heads, derive from the fast-cutting montage style of MTV. Their use as narrative punctuation to reveal character and express emotion, though always in settings where one would expect to hear music, comes from the Broadway or Hollywood musical, and here, too, the film’s characters deliver the songs. Byrne grafts documentary devices on to standard generic forms, particularly the romantic comedy and love story, though there are also elements of social satire. The roving narrator device recalls an earlier intrusive narrator in Thornton Wilder’s play Our Town (1938), and the interwoven multiple narratives can be found in Robert Altman’s Nashville (1975). Byrne was fully conscious of the hybridizing tendencies of his film, arguing that stealing and mixing was fine so long as it was done with panache.

Irony came to be seen as a pillar of postmodernism. True Stories’ tone is, however, only ostensibly ironic. A New York hipster, Byrne sounds wide-eyed with wonder and deadpan in the same breath as we meet such curious characters as the Cute Woman, the Lying Woman, the Lazy Woman (who never gets out of bed), and “dancing fool” Louis Fyne, who advertises for a partner with a sign outside his house saying “Wife Wanted.”

“Dancing fool” Louis Fyne (John Goodman) performs Talking Heads’ “Wild Wild Life”

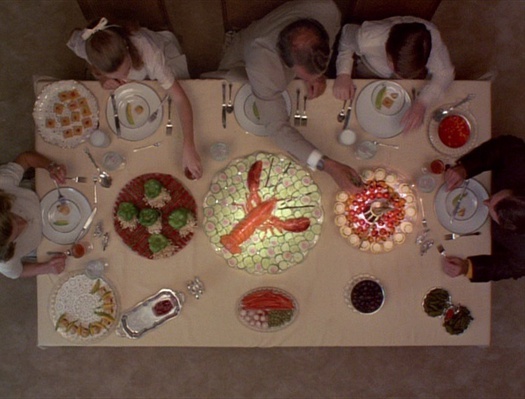

“They got that commercial attitude.” The Lazy Woman (Swoosie Kurtz) channel-hops

In his song “The Big Country” (1978), Byrne had looked down from his seat on a plane at the folksy communities of Middle America and seemed to be eulogizing the homeland, until he declared, “I wouldn’t live there if you paid me.” Now, visiting Virgil’s mall, he paints a sympathetic picture of consumers choosing to shop where it is convenient, clean and there are bargains to be found. “People here are inventing their own system of beliefs,” he explains. “They’re creating it, doing it, selling it, making it up as they go along.” Kay Culver, the immaculately groomed wife of Earl Culver, a civic leader, introduces the mall’s fashion show — “Shopping is a feeling,” she lilts. “Sometimes I get a wobbly feeling. I have a commercial feeling. Be sexy in business. Be successful at night” — before launching into “Dream Operator,” a song full of silky-sweet yearning.

“From the dream factory, a bonanza of beauty.” The fashion show at Virgil’s mall

At her house, Byrne tells her he saw the show and liked it. Driving around town, he cruises by some bungalow homes. “Look at this. Who can say it isn’t beautiful? Sky. Bricks ... Four-car garage. Hope. Fear. Excitement. Satisfaction.”

Yet this empty Texas range is also an “imaginary landscape,” in Earl Culver’s words, where postmodern people out to invent new belief systems, new lives and new products (Varicorp’s personnel are leaving to start up creative computer businesses) are becoming disconnected from history and politics.

“Mainframe. Microprocessor. Semi-conductor.” Earl Culver (Spalding Gray) demonstrates the future of Virgil

The only politics we encounter in True Stories are wildly incoherent conspiracy theories disseminated from, of all places, a preacher’s pulpit. Virgil might — or might not — be a fine place to raise children, but when Culver points out that some people are declining to have them now “what with the end of the world coming up and all,” Byrne hastily agrees he has no plans to procreate. In the next scene, we meet a prowling gang of Virgil’s youngsters, tribally clad in the same green T-shirt and petulantly chanting, “I wanna video. I wanna rock and roll. Take me to the shopping mall.” The Lazy Woman idly channel-hops, shouting with excitement at the ads and reeling off the titles of news programs, which she clearly regards as meaningless. In “People Like Us,” the anthemic song he has been working up to throughout True Stories, Louis Fyne confides that ordinary people “don’t want freedom. We don’t want justice. We just want someone to love.” The song is so heartfelt and touching that it is easy to overlook his alarming confession. It works for Louis, though, and he finds a mate.

“Artificial intelligence, robots, they’d like that, wouldn’t they?” Conspiracy theories from the Preacher’s pulpit

“One and one does not equal two, no sir, no sir.” The Preacher (John Ingle) and choir perform “Puzzling Evidence”

“One and one does not equal two, no sir, no sir.” The Preacher (John Ingle) and choir perform “Puzzling Evidence”

In 1985, while True Stories was in production, Byrne co-directed a video for “Road to Nowhere,” a song by Talking Heads. Like the film, the video begins and ends with an image of the open road stretching to the horizon, and like the film, its answer to the apparent negation of “nowhere” lies in the consolation of community. In Hiding in the Light, cultural critic Dick Hebdige identifies the “Road to Nowhere” video as firmly located within postmodernism because of the way it deploys humor — “the deconstructions and alienation effects are jokes rather than history lessons” — and he notes that its tone and the hope it invests in ordinary people are essentially affirmative. Hebdige goes so far as to claim that the kind of laughter inspired by the video could help to usher in a “new order.”

In his True Stories book, Byrne describes the Infomart (1985), a huge market for the information technology industry modeled on the Crystal Palace, built by the property developer Trammell Crow as part of the Dallas Market Center. The film-maker’s response to the weirdness and audacity of this postmodern conceit was a mixture of laughter and admiration. True Stories’ dramatic structure grew from images like this encountered on his research visits to Texas. “The thing about it is,” writes Byrne, “all of these people [in the film] are right. None of them is wrong. They are setting a good example, and in this film and book I’m teaching myself to appreciate them.” The indeterminacies, the cool ironic posture that ultimately repudiates irony, the final celebration and endorsement of the town’s “special-ness,” show Byrne coming to terms with the future implications of his pop-ethnographic field trip. The eccentric inhabitants of Virgil, engaged in finding their own ways to live, are building a little Utopia, as Byrne called it, a postmodern “City of Dreams” — in the film’s final song — showing what might be possible.

This essay was first published in Postmodernism: Style and Subversion, 1970-1990 edited by Glenn Adamson and Jane Pavitt (V&A Publishing, 2011) and appears here with the publisher’s permission.

True Stories has only ever been available on DVD in a panned and scanned version, as shown in the images here, and a corrected widescreen reissue is long overdue. The film seems like a perfect candidate for the Criterion Collection, or a British Film Institute release.

See also:

Did We Ever Stop Being Postmodern?

David Byrne in the Round

Unclassifiable Book: The New Sins