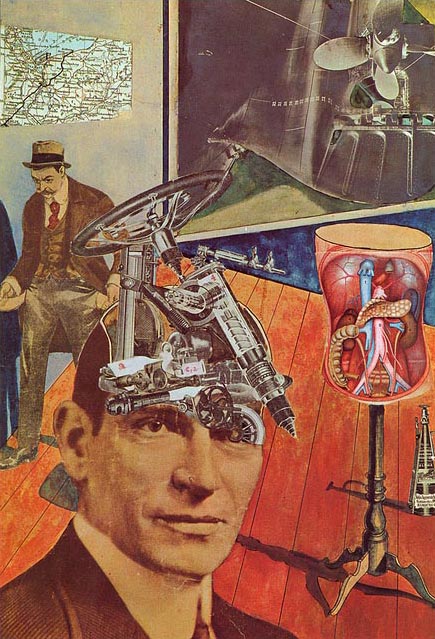

Raoul Hausmann, Tatlin at Home, photomontage, 1920. Source: Flickr

At Pinterest, which I joined recently, I have started a couple of boards related to collage, one devoted to contemporary work and the other to the history of collage from the 1920s to the 1990s. I subscribe to the view expressed by David Shields in his book Reality Hunger that collage was “the most important innovation in the art of the twentieth century” (although collage actually predates the century). It’s early days for the boards, but both will be collections of collages that I already know about but want to store in a handy place and of discoveries that are new to me. The historical board will accumulate in a broadly chronological manner until it reaches the present era, and then I suppose it will be more or less finished.

This structured style of pinning might not be the usual, more random way of filling Pinterest boards, but one thing that appeals to me about the site is the chance to contrive deliberate visual relationships between the pins, though “proximities” might be a better word since a board’s layout is shifting all the time under the pressure of new pins loaded on at the top. Still, pins stay close enough to their neighbors for visual and conceptual connections to remain. One future improvement I hope Pinterest will make is a facility allowing pins to be grouped within a board with more precision, which one could do as a matter of course on a traditional pinboard.

An early pin for the “History of Collage” board was the Dadaist Raoul Hausmann’s famous Tatlin at Home created in 1920. Perhaps I should try to get with the program more, but the decision to include this icon of Dada nose-thumbing raised many questions. An activity that promises to be quick (and with the “Pin it” button installed the process could scarcely be quicker) can turn out to be unexpectedly labour intensive. Since there are already many images of Tatlin at Home on Pinterest, the most social thing to do would be simply to repin someone else’s — the most popular Tatlin at Home pin has been repinned 23 times. The entire site is built on the idea that sharing pins without too much mulling it over is what pinners will routinely choose to do.

Pinterest search results for “Tatlin at Home”, February 4, 2014

But Tatlin at Home is a historical artifact, not a throwaway image, so which pin was the most accurate as a representation? There were large differences in color and small but nagging variations at the edges of the image. The right-hand edge seemed particularly unlikely in all the pins I looked at. Having cut out the dressmakers’ dummy containing body organs and the fire extinguisher underneath, why would Hausmann then choose to slice and crop them so awkwardly? On the other side of the collage, the man’s hand and foot comes and goes and the crop on the ship’s propeller at the top also varies. Not for the first time it seemed I would have to leave Pinterest to find the most reliable online source and with art, as a rule, this tends to be the museum that owns the piece. Before doing that, I consulted some books, seven in all, that reproduce Tatlin at Home. From William S. Rubin’s Dada & Surrealist Art (1968) to Dawn Ades’ Photomontage (revised ed. 1986), it became clear that in the original the complete edge of the dressmakers’ dummy could be seen, as well as most of the fire extinguisher (though both of these older reproductions are in black and white).

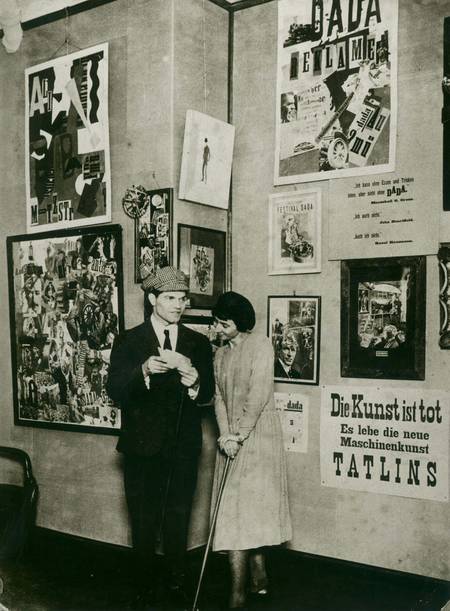

Raoul Hausmann and Hannah Höch at the International Dada Fair, Berlin, 1920

Photograph: Robert Sennecke. Source: Berlinische Galerie Museum of Modern Art

However, even these earlier images published long before the Internet are unreliable. In a photograph of Hausmann and fellow Dadaist Hannah Höch taken in 1920 at the International Dada Fair in Berlin, Tatlin at Home can be seen on the wall — Ades shows the picture on the page opposite the collage. The collage’s edge is visible and the space between the dummy and the picture’s edge is larger than in any reproduction I have seen. More of the machine-headed man’s shirt collar is showing and there is slightly more space above the propeller.

Tatlin at Home at the International Dada Fair, 1920. Source: Berlinische Galerie Museum of Modern Art

According to the illustration credits, the photograph in Ades’ book came from the Moderna Museet (Museum of Modern Art) in Stockholm. Online, the Bridgeman Art Library appears to confirm the Moderna Museet as the work’s location and the picture (with library watermark) shows a wider right-hand edge, though there is a curious line along the edge that cannot be part of the piece. Surely, then, a visit to the Moderna Museet website would provide the most reliable image of Tatlin at Home, perhaps at a size suitable for pinning, the object of my quest. A search on the site produced no evidence that the work is part of the museum’s collection any more. How could it be that such a celebrated masterpiece of photomontage — with full apologies to the anti-art spirit of Dada — has simply disappeared, seemingly while hiding in plain sight?

Eventually, in a bulletin on the Moderna Museet site, with text in Swedish, I found the answer. Tatlin is no longer at home. The original copy of the photomontage has vanished without trace. In 1971, this unforgettable satire on the new mechanical man was stolen while being transported, four years after the museum acquired it, and it has never been recovered. Any reproduction seen anywhere today can only be a copy of a copy derived from photographs taken before that date. The color photography in the countless images online looks dated because it is dated; I have a book, Dada & Surrealism (1980) by Robert Short, with a similarly toned reproduction. The full-page image is a likely source for some of the homemade scans online.

Google search results for “Tatlin at Home”, February 3, 2014

In the end, I pinned an image I found on Flickr — the one shown at the top of this post. It isn’t large and the color is probably a little too bright, but it’s sharper than most and, crucially, it shows as much of the stolen work as we are likely to get unless, by some miraculous stroke, Tatlin returns home one day none the worse for his travels, and can be photographed anew. Yet it’s so effortless now to pluck digital images without really thinking about them. As with all the other images in our public galleries of plunder, we like to imagine that we have personally captured Tatlin, that we are on familiar everyday terms with him, that we own and know this uprooted and casually disseminated “pin.” But I’ve never seen the missing original and it’s unlikely, unless there’s information you ought to share with the Swedish authorities, that you’ve had the chance to study the original in the flesh. I’ll only add that for this early apparition of a cybernaut Hausmann used a photograph of a man he found in an American magazine, who happened to remind him of the Russian avant-garde architect famous for his visionary tower. It isn’t even Tatlin in the picture.

Rick Poynor at Pinterest

See also:

The Compulsively Visual World of Pinterest