Barrie Tullett and Philippa Wood of The Caseroom Press. Photograph: Glen Robinson

After a period in the dead-technology wilderness when only diehards still cared, the typewriter has made a comeback and become a hip accessory. There is now a thriving trade in old collectable machines on eBay, Etsy, dedicated websites, and at a vintage store near you. Spin-off merchandise playing with the image of the typewriter is everywhere. Chronicle Books does a charming sleeve covered with retro drawings of typewriters — perfect to enclose a touchscreen tablet — or how about a mousepad adorned with a picture of a creamy classic Underwood that looks good enough to eat? I wandered into a new branch of Urban Outfitters in trendy Camden Town, London the other day, and high up on a display shelf, enthroned above us like a pair of mascots, were a couple of handsome manual typewriters.

The machine has become an emblem of hand-powered creativity and a reminder of what might seem, looking back, to be an attractively tactile and cool kind of authenticity. This once ubiquitous aid to communication has an appealing mechanical intricacy and a stylish variation of frame, sometimes even a beauty, that leaves our shrinking media devices looking dull and inexpressive, despite their clever interiors, and we feel a twinge of nostalgia for what has been lost.

People used to create art on typewriters and that activity has also made a comeback. This month sees the publication of Typewriter Art: A Modern Anthology (Laurence King), the first detailed survey since Alan Riddell’s in 1975 to investigate the subject’s history and present-day practice. Its author, Barrie Tullett, is a British design teacher, who with his collaborator Philippa Wood runs The Caseroom Press, an independent publishing collective in Lincoln. A typewriter artist in his own right, Tullett published A Poem to Philip Glass, a 22-page sequential abstract composed of largely non-alphabetic keyboard characters. “Graphic designers should all own at least one typewriter,” he insists, and he’s as good as his word. He has around 30. His preferred instrument was an Underwood No. 5 issued in 1934 until an Imperial Model 60 from the 1950s, with a usefully outsized A3 platen, began to edge its way into his affections.

Typewriter art is almost as old as typewriters and the first typewriter artists tended to be pictorially inclined typists or stenographers, as they were the people operating the machines. An image of a butterfly made in 1898 by Flora F.F. Stacey, an English woman, was held to be the earliest dated typewriter picture, but the craze is now thought to go back to the 1870s. The big problem with typewriter art is that its low status compared to painting and drawing and its fragility means that much of it has probably been discarded. Tullett gathers several examples of typewriter pictures, including likenesses of Queen Victoria (c. 1900) and Franklin D. Roosevelt (1943), and recent “textual portraits” by Leslie Nichols, a traditional painter. But his main interest clearly lies — as does my own — with forms of typewriter art that use the machine to generate a sophisticated new kind of non-representational type-image specific to its capabilities. Stefi Kiesler, Typo-Plastic, 1925-30, published in De Stijl magazine under the pseudonym Pietro Saga

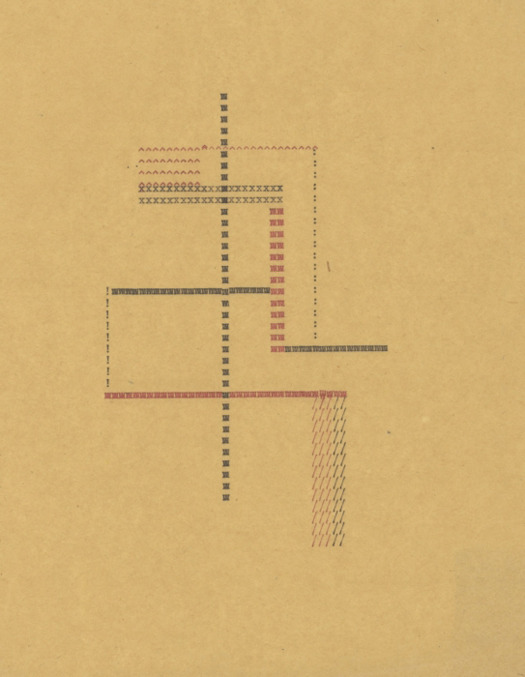

Stefi Kiesler, Typo-Plastic, 1925-30, published in De Stijl magazine under the pseudonym Pietro Saga

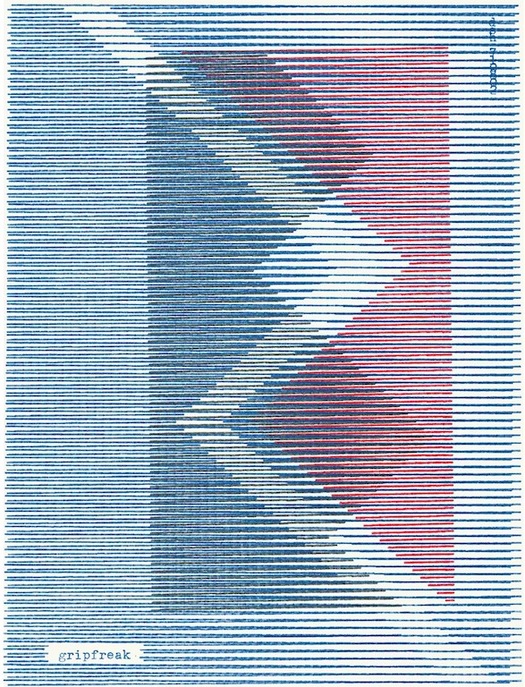

Much of this work belongs to the category of concrete poetry, which is most straightforwardly defined, writes Tullett, “as poetry that appeals to the eye and not the ear.” Although concrete poetry wasn’t formalized as a practice until the 1950s, when it became an international movement, the first pieces in this manner date from the 1920s. Tullett shows a delicate, non-verbal composition titled Typo-Plastic (above) by Stefi Kiesler, an Austrian artist and associate of the De Stijl group, as well as fluently abstract “tiksels,” or typeprints, from the same era by the Dutch artist-printer H.N. Werkman. They could easily have been created 40 years later and bear an obvious kinship with Dom Sylvester Houédard’s “typestracts” (short for typewriter abstracts) — subject of a previous DO post. The book has representative pieces by such significant figures in the visual poetry movement as Houédard, Henri Chopin and Bob Cobbing (see below).

“The use of the typewriter to produce these artworks was a pragmatic decision for the poets of the time,” writes Tullett. “It allowed the author to own the page, to dictate the visual structure without relying on the interpretation of a graphic designer, printer, compositor or editor.” We shouldn’t think of these works as exercises in typographic style, he cautions. On the other hand, there were occasions when a designer produced a full-blown typographic interpretation of the typewriter original, treating it as a kind of score that was most fully realized in performance. These acts of translation by typographers such as Hansjörg Mayer deserve renewed attention but they fall outside the scope of the book.

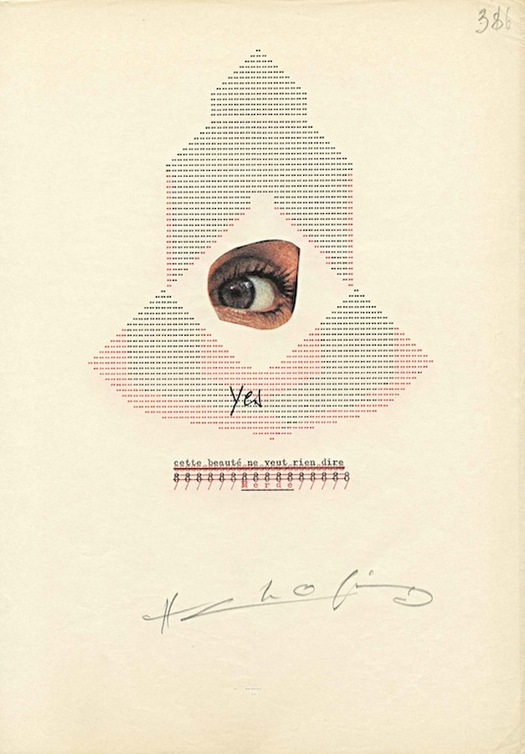

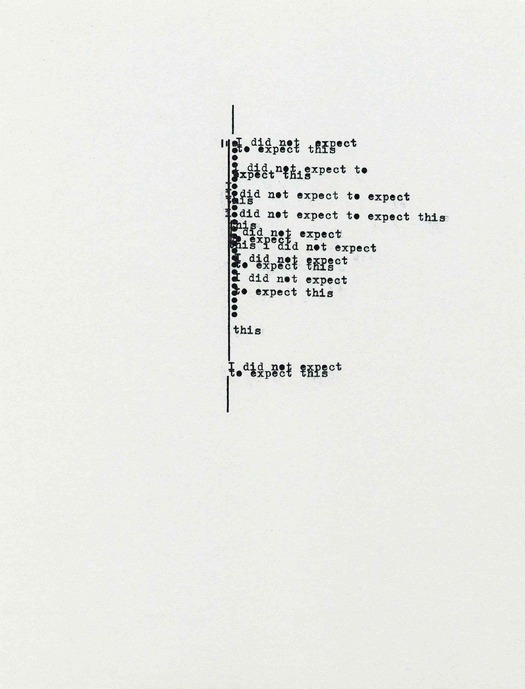

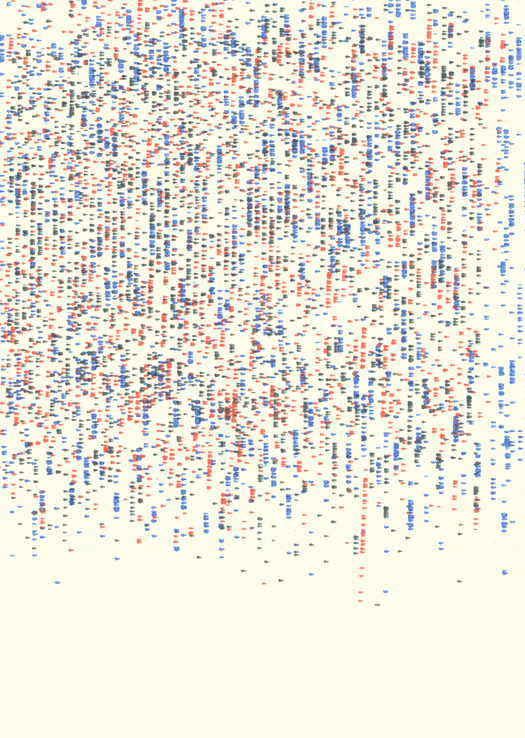

Henri Chopin, La Crevette Amoureuse, 1967-75

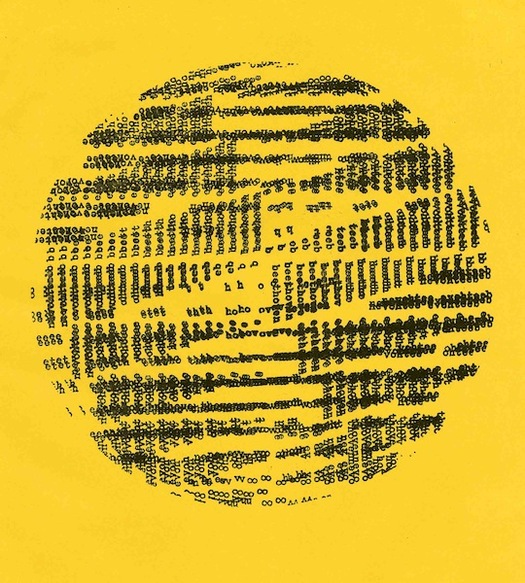

Bob Cobbing, Beethoven Today, 1970

Dom Sylvester Houédard, gripfreak, 1972. Collection: William Allen Word & Image

Marianne Holm Hansen, Typing (not writing), 2012

Barrie Tullett, Purgatory: Canto XIX — The Covetous, 2010, from A Typographic Dante

See also:

In Memoriam: My Manual Typewriter

Dom Sylvester Houédard’s Cosmic Typewriter